Ten Themes for Education

In 1995, the leadership at PVS identified ten themes of learning to integrate into its education programs.

Vision ... Our Sacred Earth ... Exploration ... Our History & Heritage, Our Traditions & Culture ... Our Pacific 'Ohana ... Our Kupuna and 'Opio ... Family ... Education ... The Health & Education of Our First People ... Our Special Multi-ethnic Community and Culture

1. Vision

Given the enormous changes that our islands face in the 21st century, we must form a collective vision of what we want our future to look like, and how we will reach that vision.

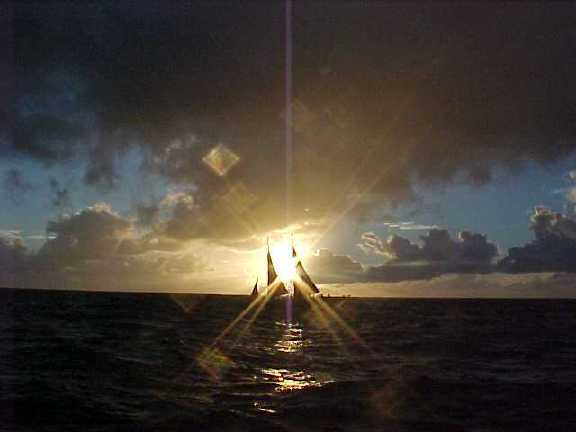

Nainoa Navigating. Photo by Sam Low

In November of 1979, Mau and I went to observe the sky at Lana'i Lookout. We would leave for Tahiti soon. I was concerned-more like a little bit afraid. It was an awesome challenge.

Then he asked, "Can you point to the direction of Tahiti?" I pointed. Then he asked, "Can you see the island?"

I was puzzled by the question. Of course I could not actually see the island; it was over 2,200 miles away. But the question was a serious one. I had to consider it carefully. Finally, I said, "I cannot see the island but I can see an image of the island in my mind."

Mau said, "Good. Don't ever lose that image or you will be lost." Then he turned to me and said, "Let's get in the car, let's go home."

That was the last lesson. Mau was telling me that I had to trust myself and that if I had a vision of where I wanted to go and held onto it, I would get there.

--Nainoa Thompson

"When the canoes arrived at Kualoa in 1995, they brought people together again. But I began to wonder, "Where do we go from here?" We need a common vision to which we can attach all our hopes and aspirations. We need to have common values to keep us steering in the right direction toward that destination. Because in the end, as individuals, we will not be able to do very much. Together, we can do much more."

--Nainoa Thompson

From an interview with Chad Baybayan by Sam Low, during the 2000 Voyage Home:

Chad's vision of wayfinding eventually evolved to contain principals that appear astonishingly universal and timeless, while, at the same time, being rooted in values that Hawaiians have come to recognize as inherent in their own unique history. Values like vision, for example.

"Our ancestors began all of their voyages with a vision," Baybayan explained during his talk to the assembled crew. "They could see another island over the horizon and they set out to find these islands for a thousand years, eventually moving from one island stepping stone to another across a space that is larger than all of the continents of Europe combined."

"After many years, I began to understand that wayfinding was really a model for living," Chad continued. "Once you have the vision of a landfall over the horizon, you need to develop a plan to get there, how you are going to navigate, how much food you need. You must evaluate the kinds of skills you need to carry out the plan and then you must train yourself to get those skills. You need discipline to train. Then, when you leave land, you must have a cohesive crew - a team - and that requires aloha - a deep respect for each other. The key to wayfinding is to employ all these values. You are talking about running a ship, getting everybody on board to support the intent of the voyage, and getting everybody to work together. So it's all there - vision, planning, training, discipline and aloha for others. After a while, if you apply all those values, it becomes a way of life."

Chad Baybayan's concept of wayfinding is not exclusive to him. It is, in fact, a voyaging subculture shared by everyone who is attracted to the canoe and who sticks around long enough to learn the lessons it has to teach.

In the last decade or so, the philosophy of wayfinding has "moved ashore" so to speak. New words have entered the wayfinding vocabulary, "stewardship" for example, or "sustainable environments." Lessons learned at sea are now being applied to the land. The ancient philosophy of wayfinding is now merging with the new world view of environmentalism, as Chad explains:

"To be a wayfinder, you need certain skills - a strong background in ocean sciences, oceanography, meteorology, environmental sciences - so that you have a strong grounding in how the environment works. When you voyage, you become much more attuned to nature. You begin to see the canoe as nothing more than a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal those resources well. We have learned to do that. Now we have to look at our islands, and eventually the planet, in the same way. We need to learn to be good stewards."

This new vision is at the core of the Voyaging Society's "Malama Hawaii" program which we celebrate on this voyage home.

Chad Steering. Photo by Sam Low

2. Our Sacred Earth

Balancing human needs and nature was one of the greatest accomplishments of the Hawaiian people, and recreating this balance in these modern times is one of our greatest challenges.

On the Search for Logs to Build a Voyaging Canoe, Hawai‘iloa, in 1992: "We started in our koa forests and ended up finding that in the last eighty to a hundred years, ninety percent of our koa trees have been cut down. The ecosystem that once supported this healthy forest is in trouble. We could not find a single koa tree that was big enough and healthy enough to build one hull of a canoe."

"Our elders told me, 'You know what the answers are. To deal with the abuse here, you need to do something to renew our forests. Before you cut down somebody else's trees, you need to plant your own.' So we started a program at Kamehameha Schools to plant koa trees; and we've planted over 11,000 koa seedlings, in hopes that in 100 years, we might have forests of trees for voyaging canoes."

--Nainoa Thompson

Koa Seedling. Photo by Forest & Kim Starr

For more about Kamehameha Schools Keauhou Reforestation project and other reforestation projects, see “Restoring Native Forests in Hawaii:

The Role of Cooperative Extension” at the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, UH Manoa website.

A healthy koa tree in the Hawaiian forest. Photo by Forest & Kim Starr

On the windswept summit of Maunaloa, in an area of West Molokai known as Ka'ana, a very special project is underway. Students from Kaunakakai, Kilohana, Kualapu'u, Maunaloa Schools, their families and community volunteers are working with John Ka'imikaua's Halau, The nature Conservancy, Moanalua Gardens Foundation, University of Hawaii Extension Program, and the Plant Material Center to bring back the native forest that once grew here.

Kumu John tells of ancient Molokai chants that speak of Ka'ana as the birthplace of hula where a vast and sacred lehua forest once thrived. Accounts of Paka'a in the 16th century reveal that loulu palm thatch was once gathered from this site. Today, it is fifteen acres of pasture planted with 1200 seedlings of native plants. The area is surrounded by fence built by the Moloka'i Ranch to keep deer, cattle, and other grazing animals away from the tender new seedlings that the students and others have planted. The Nature Conservancy, University of Hawaii Extension Program, and the Plant Material Center supplies the students with native plants such as wiliwili, 'a'ali'i, ohai, and lehua. Students transplant and water the seedlings at school preparing them for planting at Ka'ana. The goal of the project is to malama Moloka'i and bring back the native forest to this sacred area. One day the dancers at Hula Piko hope to dance beneath the lehua as their ancestors once did.

See Nainoa Thompson’s “Recollections of the Building of Hawai‘iloa”, on the Search for Logs for the Voyaging Canoe Hawai'iloa; and “Sea of Islands.”

"When I was a kid I felt very lucky to be born in Hawaii - and I still do - but the reefs in Maunalua bay were still alive then, now they are dead."

--Nainoa Thompson

In the twenty-first century, the Maunalua Bay community of Kona, O‘ahu began an effort called Malama Maunalua: a community-based organization dedicated to preserving and restoring the health of the Maunalua region, the area from Kawaihoa (Koko Head area, East O’ahu) to Kūpikipiki‘ō (Black Point) to the Ko'olau ridgeline. From the top of the ridgelines to the reefs of the bay, this region needs the stewardship of the community to return to the healthy, flourishing area it once was. One project involves removing the alien algae that is choking the reefs.

Limu Huki (Pulling seaweed), 2010

Limu Huki (Pulling seaweed), 2010

"Our western thinking is that we can dominate and consume our natural environment. We know that isn't working. One of our greatest challenges today is our population growth and human demand on finite resources. In Hawai'i, we live on small islands. What a great classroom for us to understand the issues of sustainability and understand that we don't dominate the world, we're only part of it. For our lives to be of a high quality, the environment we live in needs to be of a high quality.

"At the turn of the twentieth century, there were 1.6 billion people on earth. In 1998, the 6 billionth child was born. By 2023, there will be ten billion people on this planet. Our exponential population growth has been accompanied by an exponential depletion of the natural resources that support that growth. A grade school student can do the math--such a relationship between man and his natural environment must change.

"When I was in school there were no classes in ecology, and "sustainability" wasn't even a word yet. People thought that the solution to world hunger was to harvest an infinite amount of protein from the ocean. No one believes that today. I think one of the real basic shifts needs to be in human values--we need to be educated about what our situation is, what our relationship to the place in which we live is; we need to give back as much as we take. In its simplest form that is what Malama Hawai'i is – taking care of this place, this special island home as an obligation to future generations.

"The people of Hawai'i have a unique opportunity to help bring about the right kind of changes in our values because of our place in the world--first, we are islanders and understand the limited resources of our island home; and second, we have a strong link to our native heritage. Native people throughout the world believe that the natural environment is sacred and that they must live in balance with it to survive."

--Nainoa Thompson

Students from Michelle Kapana Baird’s Kaiser High School voyaging program working on a kalo lo‘i. Photo by Monte Costa

3. Exploration

Exploring and learning about the world around us is essential to finding solutions to the difficult issues of our times.

"When we voyage, and I mean voyage anywhere, not just in canoes, but in our minds, new doors of knowledge will open, and that’s what this voyage is all about..it’s about taking on a challenge to learn. If we inspire even one of our children to do the same, then we will have succeeded."

– Nainoa Thompson, September 20, 1999, the day of departure for the challenge of navigating from Mangareva to Rapa Nui, the remotest, most difficult island to navigate to in Polynesia).

"One of the important themes of this voyage to Rapa Nui is why we explore, and the process of exploring, envisioning something that's important in our lives, recognizing that we need to do research and plan out the details; that we need to build a community to support this kind of effort, that we have to prepare and train, that we need to take risk somewhere along the line to achieve things that are of great importance. We hope that this process of exploring we engage in inspires young people to visualize and pursue their own dreams.

"We've been exploring physically outward in the last 25 years into the Pacific, and certain themes have emerged as important to us – education and protecting and preserving our beautiful environment, our rich heritage and culture, and our kinship with other Pacific Island nations who are really our ancestral families.

"When we add all these themes up, we find they are really about relationships – among all of us as members of this community and between all of us and this beautiful place in which we live. Our work may be in history and culture, but it's really about finding ways in which we can all participate in trying to envision and shape the kind of future that we want not just for us, but for future generations.

"Learning is all about taking on a challenge, no matter what the outcome may be. When we accept the challenge we open ourselves to new insight and knowledge."

--Nainoa Thompson

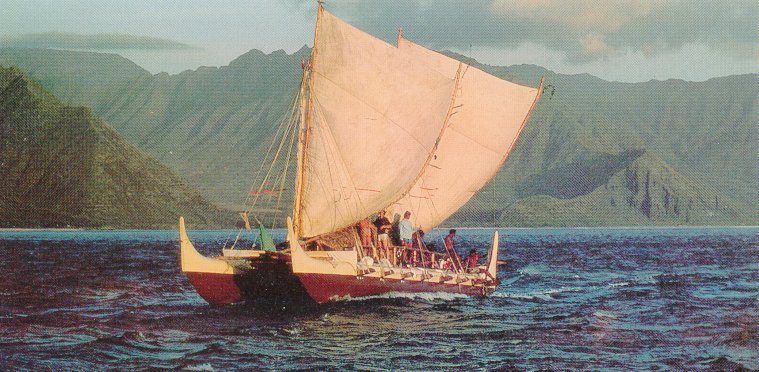

Hokule‘a 1976

"The Polynesian Voyaging Society was founded for the purpose of scientific inquiry and exploration: How did the Polynesians discover and settle small islands in ten million square miles of ocean, geographically the largest "nation" on earth? How did they build canoes from limited resources on small islands? How did communities come together to combine resources, material, and manpower, to build and sail these voyaging canoes? How did they navigate without instruments, guiding themselves across open ocean distances of 2500 miles? And how did they transport the food necessary for societies to survive, then flourish on uninhabited islands?

"Over the last 25 years PVS has built two voyaging canoes, Hokule'a and Hawai'iloa, and conducted six open ocean voyages throughout the Polynesian Triangle to answer these questions. The 1999 voyage to Rapa Nui was once again about exploration: How did our ancestors find this remote, isolated island smaller than Ni'ihau, the smallest major island in the Hawaiian Archipelago? How did they get there 1450 miles against the wind from Mangareva, where the first settlers are believed to have originated?

"Once again we were challenged and excited about the opportunity to look for answers, about learning, about discovering something new."

--Nainoa Thompson

4. Our History & Heritage, Our Traditions & Culture

A precious inheritance defines who we are, where we come from, and why we should be proud.

"Our ancestors sailed across a vast ocean, one third of the earth's surface, and to accomplish this great feat they needed the vision to see islands over the horizon, the ability to plan intentional voyages of discovery, the discipline to train physically and mentally, the courage to take risks, and a deep sense of aloha to bind the crew together during the voyage. These are Hawaiian values but they are also universal values. They worked in the past and they will work today."

-- Nainoa Thompson

"In 1976, Hokule'a sailed on its historic voyage to Tahiti. Kawika Kapahulehua skippered the canoe, and Mau Piailug was the navigator. Never before had Mau been on such a long journey, never before had he been south of the equator where he could not see the North Star, a key guide for his travels. Nevertheless, sensing his way over 2,500 miles, using clues from the ocean world and the heavens, clues often unnoticed to the untrained eye, he found, after 30 days of sailing, the island of Mataiva, an atoll in the Tuamotu island group.

"At the arrival into Pape'ete Harbor, over half the island was there, more than 17,000 people. The canoe came in, touched the beach.

"There was an immediate response of excitement by everybody, including the children. So many children got onto the canoe it sunk the stern. We were politely trying to get them off the rigging and everything else, just for the safety of the canoe. None of us were prepared for that kind of cultural response -- something very important was happening. These people have great traditions and they have great genealogies of canoes and great navigators. What they didn't have was a canoe. And when Hokule'a arrived at the beach, there was a spontaneous renewal, I think, of both the affirmation of what a great heritage we come from, but also a renewal of the spirit of who we are as a people today."

--Nainoa Thompson

Pape'ete Harbor, 1976

5. Our Pacific ‘Ohana

One of mankind's greatest needs is to feel a sense of kinship with other people, and establish caring relationships with one another.

"The mana in this canoe comes from all the people in the past who have sailed aboard Hokule'a and cared for her. I think of the literally thousands of people who have come down and given to the canoe when she was in dry dock. I think of Bruno Schmidt in Mangareva who showed up with his truck every morning to take us wherever we needed to go. I think of the people in Tautira and Rarotonga and Aotearoa and the Marquesas and Rapa Nui who did the same. The list is endless. All of this malama-this caring-adds to the mana of the canoe. It is intangible but it is alive and well. We can all feel it. I just want to acknowledge it."

--Bruce Blankenfeld

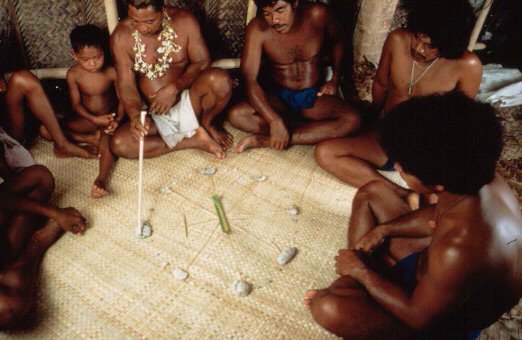

"Year after year Mau Piailug [from the Micronesian island of Satawal] came and took us by the hand as we prepared for our voyages. He cares about people, about tradition; he has a vision. His impact will be carried beyond himself. His teaching has become his legacy, and he will not soon be forgotten.

"On the 1980 voyage to Tahiti Mau made a fundamental step. He became, instead of the navigator, our teacher. An incredible feat, considering he could barely speak English. He was the one who came to Hawai'i and made this enormous cultural jump. I believe that the great genius of Mau Piailug is not just in being a navigator, but that he could cross great cultural bridges and help us find our way at sea. All of this came from a very powerful sense of caring on his part."

--Nainoa Thompson

Mau Piailug, teaching navigation on Satawal

Nainoa – Tautira, Tahiti, 1976: "Two days before we left I was sleeping in my room and about four o'clock in the morning I woke up. Puaniho's wife was pulling me by my toes and waving to me to go outside. So I got my clothes on and we went outside. She couldn't speak any English and so she just signaled to get in her truck. We drove all the way back to Tautira, early in the morning, as the sun came up. We went to every house, every house, and we stopped and they filled that truck up with food. By the time we drove back to Pape'ete I was sitting on a mound of food - banana, taro, mango, uru - everything. There was no verbal communication. Puaniho drove right up to the canoe. He knew exactly what he was going to do. They put all the food aboard and then he drove off."

Puaniho Tutaha, Tautira, Tahiti

"Somehow Puaniho knew that I was nervous about the trip. I was even considering not going. The next day he came back and he had carved a wooden cross, a necklace, and he gave it to me. That was when I knew that I had to go."

When Nainoa returned to Hawai'i aboard Hokule'a in 1976, he told his grandmother, Clorinda Lucas, and his parents, Pinky and Laura Thompson about Puaniho and the hospitality the crew had received in Tautira.

"I told that story to my grandmother and to my mom and dad and you can imagine what that meant to them. They knew that I was afraid - that I felt that I was not prepared. And these Tahitians knew what to do to care for me and the crew by giving us what they could - their food and their aloha" (From Journal, Tahiti to Hawai‘i, February 5-27, 2000, by Sam Low).

Nainoa – Aotearoa, 1984: Hector was sitting by the campfire. Suddenly he got up and began to orate in Maori. I didn't know what he was saying, but I could see in the yellow light from the lanterns tears streaming down his face.

When he finished he said, "In this land, we still have our canoe buried. In this land, we still have our language and we trace our genealogies back to the canoes our ancestors arrived on. But we have lost our pride and the dignity of our traditions. If you are going to bring Hokule'a here, that will help bring it back. Whatever you need to do, I am with you all the way."

When he first met me, all Hector knew was that I was some Hawaiian who wanted to come down and study the stars, but he didn't know why. When I was up on the hill, I think Matey told him about Hokule'a and what we were trying to do. Somehow, John Rangihau knew that Hector would be the one to care for me.

From that point on, all during his vacation, Hector drove me to places where I could study the stars. We drove a long distance to Te Reinga, the northern tip of the island. The beach there was ninety miles long. We went to the lighthouse, and from there, I could see the horizon to the east, west, and north. At night, I would study the stars and Hector would sleep in the car. At dawn, he would drive back while I would sleep in the car.

--Nainoa Thompson from Recollections of the Voyage of Rediscovery: 1985-1987

Hector Busby, greeting the Hokule‘a Crew in Aotearoa, 1985

Nainoa – Aotearoa, 1985: "When Hokule'a reached Aotearoa in 1985, Sir James Henare, the most revered of the elders of Tai Tokerau, got up and spoke. He said, 'You've proven that it could be done. And you've also proven that our ancestors had done it.' This was a very special moment for him, a very special occasion, and he laughed and he cried. I recognized from him that we already come from a powerful heritage and ancestry. The canoe, on its voyages, is just one instrument to connect to that. Sir James Henare also made an incredible statement '... because the five tribes of Tai Tokerau trace their ancestry from the names of the canoes they arrived in, and because you people from Hawai'i came by canoe, therefore by our traditions, you must be the sixth tribe of Tai Tokerau.' We didn't know what to make of that, such a powerful statement. But I do know-remember in my point of view, the most powerful things are these relationships – in a few sentences, Sir James Henare had connected us to his people. And he said that all the descendants from those who sailed the canoe are family in Tai Tokerau."

--Nainoa Thompson

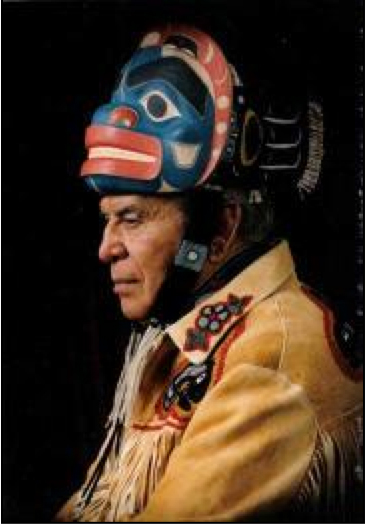

"Judson Brown [Tlingit Elder of Alaska] was the spiritual link between his people and ours. His role was critical, not just in getting the trees, but in the celebration of culture. Even though Hawaiians and Alaskans are different people--defined by their different environments, languages and cultures--in the end, the native Alaskans share the same kinds of concerns and hopes and aspirations as we do. They believe that it is very important for the health of their people to rebuild their culture, to rebuild their traditions. [Judson Brown made the donation of logs from the native Alaskan tribal corporation Sealaska for the hulls of the voyaging canoe Hawai'iloa in 1991.]"

At the koa forest Judson said, "When you sail, don't be afraid, because when you take your voyage we will be with you. When the north wind blows, take a moment to recognize that the wind is our people sailing with you." He was clear that the voyage wasn't about navigation. It wasn't about building a canoe. It wasn't about the stars. It was about bringing people together. He always saw Hawai'iloa as a celebration of a connection between native cultures.

--Nainoa Thompson, from “Sacred Forests” by Sam Low

6. Our Kupuna and ‘Opio

We recognize the need to treat our elders with respect and dignity and the vital importance of early childhood care and education.

For stories about kupuna and Nainoa’s respect for their advice in in the PVS search of logs for a voyaging canoe, see Sam Low's “Sacred Forests.”

For stories about Kapu Na Keiki ("Hold Sacred the Children") and Nainoa’s thoughts on educating our youth and taking care of those in need, see the August 2006 Newsletter.

7. Family

From healthy families come healthy communities.

Students from Kaunakakai, Kilohana, Kualapu'u, Maunaloa Schools, their families and community volunteers are working with John Ka'imikaua's Halau, The nature Conservancy, Moanalua Gardens Foundation, University of Hawaii Extension Program, and the Plant Material Center to bring back the native forest that once grew at Ka‘ana, Moloka‘i.

For thoughts on family, see portraits of crew members by Sam Low during the 2000 voyage home from Tahiti.

8. The Importance of Education

The key to perpetuating values and culture and preparing ourselves to face the challenges of the future.

From an Interview in The Kamehameha Journal of Education (Fall 1994), by Gisela E. Speidel and Kristina Inn:

Nainoa sees it as his responsibility to teach the youth about sailing the way the ancients did. He tells us of his work with high school students. The students plan a voyage in a double-hulled canoe along the coast of the Big Island; they figure out the provisions they need, they calculate the time it takes for them to travel under ordinary weather conditions, they determine who will do what to prepare for the trip and once they are on board. They submit their plan (and alternative ones for other weather conditions) to Nainoa who checks the plan for feasibility; if he sees any problems, he asks questions to help the students focus on the difficulties in their plan. The students are trained in handling the boat-they must have the skills-and their plan must be feasible. But in the end, the plan and the voyage are the students' sole responsibility-no adult is on the boat; they sail alone, by themselves. He insists, "It must be their plan, their responsibility, their voyage." Perhaps in teaching these students about seamanship, Nainoa is instinctively drawing upon how he himself has learned what he now wishes to transmit.

"When I think back on my life, it's clear that I had no way of knowing that I would be here now doing what I am doing. When I began studying in school and gaining knowledge, I sometimes doubted the importance of that effort. But it's the knowledge that I gained with the help of so many teachers that has allowed me to contribute to what we have done over the last 25 years--to rediscover our culture and heritage.

"So I hope that all our children will keep on pursuing knowledge. None of us knows where we are going, but at some point in our lives, that knowledge will allow us to jump off into the unknown, to take on new challenges, and that's what I consider before every one of these voyages-the challenge. Learning is all about taking on a challenge, no matter what the outcome may be. When we accept a challenge, we open ourselves to new insight and knowledge."

--Nainoa Thompson

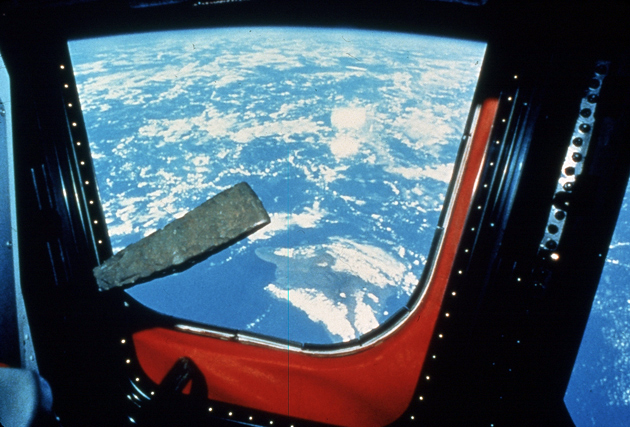

"One person who understood the challenges we face and the role of education in meeting the challenge was Colonel Lacy Veach, raised in Hawai'i. He joined the Air Force, flew with the Thunderbird pilots, flew in Vietnam, was shot down twice. A man of great passion. Lacy was Hawai'i's second astronaut with NASA after Ellison Onizuka, and he flew on two missions of the space shuttle Columbia. He loved Hawai'i and its voyaging canoes and saw immediately the connection between these canoes and Hawai'i's future. On one of his shuttle flights, Lacy was able to stow away an adze stone from his grandfather. The stone came from Keanakako'i, an adze quarry located 12,500 feet up on the slopes of Mauna Kea, a special place where ancient Hawaiians worked in sub-zero temperature to make adzes; Lacy took a photo of his adze floating in space with Mauna Kea behind it framed by the cockpit window, as he was flying 160 miles above earth.

"Lacy passed away a year and a half ago from cancer. Before he died, he told me, "Nainoa, you can never believe the beauty of island Earth until you see it in its entirety from space." He was the world's greatest optimist, but he always felt a great concern over the imbalance between human needs and the limited resources of our small planet; over the danger of exponential population growth and depletion of natural resources to support that growth. He would talk about how the 21st century was going to be very different from the century we're leaving. There would be great challenges ahead; there would be places on this planet that are going to be, by our own definition of quality of life, extremely substandard.

"On one of his shuttle flights, a fellow crew member woke Lacy up and told him to look out the window--they were passing over the Hawaiian Islands. Lacey could see all the Islands, and he could see his whole spirit and soul here. He saw the entire planet in one vision. "The best place to think about the fate of our planet is right here in the islands. If we can create a model for well-being here in Hawai'i, we can make a contribution to the entire world." He wanted to come home. On his visits to the islands, he talked with schoolchildren. On one visit, a child went up to him and poked him. I heard him tell another child, "I'm just checking to see if he's real." And then another child asked him, "What does it take to be an astronaut?" And Lacy said, "You've got to believe in your dreams, and you've got to be hard-headed enough to never let them go.

"One day he told me, 'I'm going to fly two more times in the shuttle. Then I'm coming home.' He'd been away from Hawai'i since high school. 'I'm coming home to help children who want to learn.'"

--Nainoa Thompson

9. The Health & Education of Our First People

Hawaiian culture and values are vital to shaping a healthy future for Hawai'i.

"I believe we are a product of our experiences. We are a part of the influences of things that we go through in our lives. On the canoes we have experiences that make our lives feel very special. But that's not true for all Native Hawaiians. If you take a look at the socioeconomic and the health indexes and statistics of our time, our people are in trouble. Why is that? What happened to such a rich people, such great explorers, the best in the world, and a culture that evolved over 2,000 years-not just exploring on canoes, but living in healthy, balanced, sustainable ways on our islands?

"Something happened in the last 200 years with the introduction of relationships from the outside. For one thing, our population declined. The estimates suggest that there were 800,000 pure Hawaiians prior to the European arrival. Over 100 years later there's only 40,000. Think about it; count 20 people you know. That means that of the 20, 19 died.

"And even today, though our Native Hawaiian population is growing, our health statistics are still poor. I think when the outside world comes in and dominates a people, you end up with cultural abuse. And we know the effects of abuse on a single individual-how it degrades one's self-esteem and lowers the immune system. If we consider this, then perhaps it's not so hard to understand why our people are the unhealthiest ethnic group in Hawai'i-in our own homeland. What do we do? I think good things, incredible things are going on. If abuse is the problem, then we need to get rid of the problem and replace abuse with renewal. This is what voyaging is about-to renew the pride and the dignity of our people, to make them strong so they can have the will to guide their own lives.

"Jacko Thatcher, a Maori from Aotearoa, showed me how voyaging can lead to renewal. He is the individual who was chosen to be the navigator of Te 'Aurere when it sailed from Aotearoa to Hawai'i. The Maori did not choose a real experienced seaman to be trained in navigation. In the wisdom of the people that made the selection in Aotearoa, they chose an educator who would go back and teach their children. I remember training Jacko – he was not very confident because of his lack of sea experience. He was afraid. I would always sense a discomfort in him. He did not think he could make the voyage, yet he always said, "I'm willing to try." When he brought Te 'Aurere to Hawai'i, guided by the stars, and he did a haka, his traditional dance, on Hawaiian soil, he was full of pride; it was an expression of a renewal of the spirit."

Jacko Thatcher at Kualoa Regional Park

"It's from Kenny Brown and my father that I understand how voyaging is connected to health in a very spiritual way. Kenny says, "If you want to help our people, then strengthen their spirit"; my dad says, "If you want our people to be healthy, raise their self-esteem." And I didn't realize till recently that my dad and Kenny were saying the same thing. We have to get our people to believe in themselves, to be strong. When you have healthy individuals, you end up with healthy families, and from healthy families come healthy communities.

"So our part is to step into the lives of our children, to influence their lives in a positive way through education. Consider our children spend 33,000 days in our educational system until the time they graduate. But among part-Hawaiians, less than 50% graduate from high school. We want to step in there. We want to bring education to the children. We want to get to those children who really want to learn and be motivated about the things that are so important ... like the ocean."

Students on E Ala after sailing the canoe on a voyage along the Kona Coast.

"Then I think they will be excited to want to learn. We want to integrate the academic work to improve literacy with very special and rare experiences that connect learning to real achievements. We want to have children do things that they want to do, to challenge themselves. If they're truly going to have powerful learning experiences, it must come from inside of them, from the challenge inside of them. What we want to do is provide that challenge through the canoes, through learning about the ocean. And hopefully, the children will recognize from the voyaging experience that they need to become a union of people, working together to make great changes. I know from being on crews that the navigator is only one person in that crew, only a part of the whole. He is only the eyes of the canoe, the crew does all the rest. Working together as a community is the only way that we can reach our goals.

"We also want to touch our children in a much deeper way than the school system does now. We want them to get in touch with their ancestry, connect them to their past, and give them the hope to look for a bright future."

--Nainoa Thompson

10. Our Special Multiethnic Community

Hawai'i's contribution to global peace.

"Our canoes have been envisioned, maintained, and sailed by all the people of Hawai'i, regardless of race or religion. We have got to remember that we are all one people."

--Pinky Thompson

"When I look at the many shades and complexions that share Hokule'a's deck I realize it is more than the Hawaiian community that's represented here. It is Hawaii's community of today who sail her."

--Chad Baybayan

Summer voyaging program, 1998

Hawaiian writer John Dominis Holt (1919-1993), one of Nainoa‘s mentors (see “Sacred Forests”), remembers through its rich and varied food the special multiethnic community of Hawai‘i where he grew up:

As I recall Hawai'i before statehood, computers, and nuclear warheads, it was a world of great eating and drinking bouts, flavored by the introduction of customs and habits of the diverse peoples who came to settle in Hawai'i. The exotic foods of Asia, Europe, and America and the salty, fatty cuisine that became labeled as Hawaiian were eaten by all. The old fish market downtown flourished with foods of all kinds and became a sort of esplanade, a gathering place, for both fashionable and ordinary people alike. Everyone went to market, not only to shop, but to meet friends.

The Chinese gave great dinners of stuffed oysters, shrimp Cantonese, egg rolls, broiled squab, hum hah pork, lop cheong, sweet-sour cabbage and meat, kau yuk, and many other delicacies.

The Hawaiians celebrated by giving lu'au, replete with kalua pua'a (pig cooked in an imu, or underground oven), various types of raw fish and limu (seaweed), chicken or squid fixed with taro leaves and coconut milk, and sweet potatoes. The feast was topped off with rich, custard-filled cream cakes and washed down with soda pop of all flavors. The tables were decorated with fern leaves, hibiscus flowers, bananas, papayas, breadfruit, and mangoes.

The Portuguese cooked great pieces of pickled pork. They produced marvelous breads and a tasty doughnut called malasadas for feast days and Holy Ghost celebrations.

The Japanese, at New Year’s, would spend a half-year’s wages on wonderfully decorative and imaginative delicacies. Sweet rice-paste cakes called mochi were filled with a black bean mixture called black sugar. Fish was prepared in the most stylish and incredible ways; a simulated net carved from a great turnip would cover a whole fish. This splendid display would be given a final embellishment of flower-like decorations carved from carrots and radishes.

The Puerto Rican people feasted on cundudis, pigeon peas and rice, and pateles made with mashed green bananas that served the purpose of corn meal in a tamale. They also served deliciously flavored roasted bits of beef or pork.

At wedding celebrations, the Filipino people roasted whole pigs over a spit and prepared a strongly spiced dish made from chicken or pork, called adobo. It was a marvelous sight to come upon a little house in the cane field camps of the sugar plantations and find the golden-crusted carcass of a hog being patiently turned on a spit over hot coals. It was even more rewarding to stay and be offered bits of the barbecued pork, especially the skin, roasted crisp with the consistency of peanut brittle. (From Recollections, 1993)

As he recalls his upbringing in the 1950's in Niu Valley, Kona district, O‘ahu, Nainoa remembers those he learned from outside of his family not by ethnicity, but by the care they took to help him learn about himself and his world. Two of them stand out in his the introduction to his biography. One was Yoshio Kawano, the milkman:

Nainoa grew up on his grandfather's dairy and chicken farm in Niu Valley-when the valley was still all country. It was Yoshio Kawano, the milkman, who introduced the ocean to Nainoa. Dawn would often find Nainoa sitting on Yoshi's doorstep, waiting for Yoshi to take him fishing. Yoshi would bundle Nainoa into the old car, and off they'd go to fish in the streams or on the reefs. He came to be at home with the ocean, feeling the wind, the rain, the spray against his body. To the five-year-old Nainoa, the ocean was huge, wild, free, and open.

(See "Exploring Oshima roots" by Derek Ferrar, on Nainoa’s search for Yoshio Kawano‘s home town in Japan during the Oshima-Hiroshima portion of Hokule‘a’s 2007 Ku Holo Komohana voyage to Japan.)

One of the teachers Nainoa remembers was Mrs. Hefty:

"It was really important to me that I could trust a teacher and feel the teacher cared for me; Mrs. Hefty, she was great! She was my fifth-grade teacher. She was so understanding and sincere; she cared for me. Intuitively, she knew how to reach out to me. With her, I had no fear of failing; I could learn anything from her." Mrs. Hefty must have, indeed, been special. She lives on the mainland now, but Nainoa still corresponds with her, and whenever he comes back home from one of his long and dangerous voyages on Hokule'a, a letter is there from Mrs. Hefty to welcome him back and to congratulate him.

On Global Peace, during the Oshima-Hiroshima portion of Hokule‘a’s 2007 Ku Holo Komohana voyage to Japan.

“In many ways I sense the people in the world are sensing and recognizing a tipping point, where we as global cultures are coming to an understanding that the pressures of human need - and that’s all of us, we all contribute to that - are meeting the limitations of the pressures on earth. The other thing I sense is the cultural tipping point which I think humanity has always had to deal with, but we’re not just throwing sticks and stones anymore. We look at a smaller world and relationships coming closer and closer to each other as global cultures and the tipping point is whether we find a way by looking at diversity as strength and acceptance and treating each other with dignity as opposed to diversity being seen through the lens of fear and intolerance. The flame symbolizes respect, hope and healing between I think the culture of Japan and the culture of Hawai’i and the canoe. The journey here is a deep one. It’s not just voyaging to a country we’ve never been to before, it’s trying to find and forge a relationship based on strengthening peace. In many ways, we have to, as individuals, find ways to encourage and promote world peace between people and the flame was one single symbol of that.”

For an essay on the diverse community that takes care of Hokule‘a, see “A Laying on of Hands” by Sam Low.