Recollections of the Building of Hawai‘iloa and the 1995 Voyages

Nainoa Thompson

Hōkūle‘a was built quickly, of modern materials mostly, and then we went right into sailing. It was an ocean project; the emphasis was on sailing her, not on building her. But when our ancestors built and sailed voyaging canoes, it required the labor and arts of the entire community, everyone working together--some collecting the materials in the forest, others weaving the sails, carving the hulls, lashing, preparing food for the voyage, or performing rituals to protect the crew at sea. So we thought that building a canoe of traditional materials would bring our entire community together, not just the sailors, but the crafts people, artists, chanters, dancers and carvers. The Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program was set up to build not just a canoe--but a sense of community--by recreating Hawaiian culture.

We started in our koa forests and ended up finding that in the last eighty to a hundred years, ninety percent of our koa trees have been cut down. The ecosystem that once supported this healthy forest is in trouble. We could not find a single koa tree that was big enough and healthy enough to build one hull of a canoe.

Shorty, Nainoa, and Clay Bertelmann Searching for Koa Logs

On our last weekend of the search, in the Kilauea Forest Reserve on the island of Hawai'i, we searched with a large team and found nothing. Everyone went back to work on Monday, but Tava Taupu and I stayed up in the forest. We decided that Tuesday, March 18, was our last day. At that point I was very project oriented--we have a job, we've got to build a canoe--but inside I was sad and depressed by the difference between what I imagined our native forests to look like and what they actually looked like. All around us were alien species and ferns uprooted by feral pigs introduced to Hawai'i in the 19th century. I saw a layer of banana poka vines twisting in the canopy from one tree to another, choking the trees.

Koa tree with rotted trunk

"There's a fence-line up ahead about a half mile," I told Tava. "I'll go up slope and we'll work toward it together to cover more ground. We'll meet at the fence. If we don't find anything, that will be it."

Tava nodded and began moving forward. We knew that we were not going to find any trees, that the search was going to fail, but it was our last chance. When I saw Tava and he saw me, from that moment, we never spoke. We each knew the other had not found a tree. We did not even walk on the same side of the road. Tava walked behind me, as if we were repelled by each other. We were very depressed. We had not achieved what we so much wanted to achieve. But beyond that, I think the loss of the forest was eroding something inside of us.

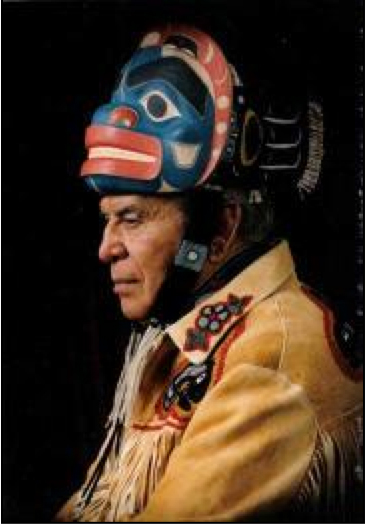

There was another source of trees for Hawaiian canoes. We knew trees from the Pacific Northwest drifted to Hawai'i, and our ancestors cherished them and built canoes from them. Herb Kane and I had talked about our project earlier with his old friend, Tlingit elder Judson Brown, who was chairman of the board of Sealaska, a native Alaskan timber corporation.

Judson Brown (1912-1998; see biographical note below). Photo by Kate Kokotovich

Judson fully understood what we were trying to do. It was about reviving our culture, and he knew the trees were the tools for doing that. Without hesitation, he said, "We will give you trees for your canoe if you need them."

After we ended our search for koa trees, we called on Judson and Sealaska and gave them the specifications for the two trees we needed. They said they would search, and they did for six weeks in the remotest parts of their forests in Alaska. Then they called us up and said, "We have the trees of your specifications. But we're not going to cut them down unless you come up here and tell us it's okay. Because we believe that our people are connected to the natural environment, that the trees and the forests are family to our people. And we're not going to take the life of a family member unless we know this is what you want."

I was in charge of building a canoe. That was my narrow focus. But around this project were so many layers of values that I did not clearly see. I understood them, I felt them, but I did not see them as part of my responsibilities. I was thinking of deadlines and logistics. Judson gave me a new perspective based on the values of his elders; it's the kind of wisdom that we always seek from the older generation.

So we flew up to Alaska. We got a helicopter in Ketchikan and went west 80 miles to a remote forest on Shelikof Island. Our guide was Ernie Hillman, a forest manager for Sealaska. He had done his job.

The trees were exactly what we asked for. But when he asked me, "Shall we cut these trees down?" I couldn't answer him. I didn't want to cut the trees down. They were too beautiful, too full of life. I began to weigh the value of our project against the value of the life of the trees. I was just too troubled. Everybody got real quiet. I couldn't explain myself. The trees were breath-taking--I had never seen trees like that before, giant evergreens. I began to sense Alaska's power. There was something so very different about it, something alluring. It was very spiritual, and that made me quiet and humble. The place was so wild, so clean and still, so natural. I began to face up to the reckless changes taking place in Hawai'i, especially on O'ahu. When I was a kid I felt very lucky to be from here--and I still do--but the reefs in Maunalua Bay were still alive back then, and now they are dead. We got back on the helicopter, and no one talked. We flew back to Honolulu. The trees remained in the forest.

Something was wrong. I didn't know what it was. I talked to Auntie Agnes Cope and John Dominis Holt, our elders who were on the Board of the Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program which was supporting this project to build a canoe called Hawai'iloa. Why didn't I ask for the trees to be cut down? It was because by taking the trees out of Alaska, we were walking away from the pain and the destruction of our native Hawaiian forests. We could not take the life of a tree from another place unless we dealt with the environmental abuse in our own homeland. The answer was clear. Our elders told me, "You know what the answers are. To deal with the abuse here, you need to do something to renew our forests. Before you cut down somebody else's trees, you need to plant your own." So we started a program at Kamehameha Schools to plant koa trees; and we've planted over 11,000 koa seedlings, in hopes that in 100 years, we might have forests of trees for voyaging canoes.

Kamehameha Schools Keauhou Reforestion project

At the planting, I remember grandchildren with grandparents, a big circle of people participating in healing the forest. It was a diverse group. There was a growing sense of community. What started as a project of artisans and people within the Hawaiian voyaging community now extended out as far away as Alaska.

This event brought closure to the search for koa trees by recognizing that we had a real problem in our land. Even though the planting was symbolic, we were contributing in a way that was sending the right kind of message to our communities about replacing abuse with renewal. This became a fundamental value which began to permeate all our decisions. It was the groundwork for what guides us today--Malama Hawai'i, taking care of Hawai'i, our special island home.

Judson Brown was there at the tree-planting ceremony. He was the spiritual link between his people and ours. At the koa forest he said, "When you sail, don't be afraid, because when you take your voyage we will be with you. When the north wind blows, take a moment to recognize that the wind is our people sailing with you." He was clear that the voyage wasn't about navigation. It wasn't about building a canoe. It wasn't about the stars. It was about bringing people together. He always saw Hawai'iloa as a celebration of a connection between native cultures.

A healthy koa tree in the Hawaiian forest. Photo by Forest & Kim Starr

So we went back to Alaska, and we thanked the spirits of the forest for the gift of the trees. Wright Bowman, Jr., who would build the canoe was there. Keli'i Tau'a chanted in Hawaiian and Paul Marks chanted in Tlingit. Sylvester Peele from Hydaburg offered a Haida blessing. Before they cut the trees down, the Alaskans told us, "You take these trees. They are gifts to you. Don't ask us how much they cost. And don't ever bring them back because if you do, they're not gifts." Then they cut the trees down, took them out of the forest, and shipped them to Hawai'i. Each tree was over 200 feet tall, 400 years old, and weighed over 25 tons.

Now what do we do? We had a focus, a vision of building a voyaging canoe that people would feel was special enough to bring all their resources together. We knew to build a voyaging canoe as our ancestors did would take the effort of a healthy community.

We brought in the best--Wright Bowman, Jr., whom I consider the best canoe builder in Hawai'i. His job was to carve a 4,000-pound hull out of a 100,000-pound tree.

We also needed ten lauhala sails. We asked native weavers to help us make our sails, and they said, "No, we're not going to do that because the job is too big, and if we make a mistake, maybe you'll die." They didn't want to be responsible at first. We asked them to please try. And after about a month of coaxing, two weavers, Mrs. Nunes and Mrs. Akana, said, "Yes, we'll try." They made the first sail in 600 years big enough for a voyaging canoe. The thing that impressed me most was that it took them 13 months. We estimate about 280,000 weaves for the sail. When you put the panels up against the light, you could barely see a pinhole through them. These two ladies had reached what we felt we were searching for the most--that is pursuit of excellence in our people, in our traditions, in our heritage. And it's because of the great concern they had for our well-being that they put so much care into weaving those sails.

The building of Hawai'iloa brought together people---we estimate half-a-million man hours were spent building the canoe. No metal parts, three miles of lashing. In the end it was a journey of people coming together because they shared a common vision and values. They worked together for something they believed was special, not just to themselves but to their whole community.

We then trained for two years on the canoe. We sailed 2,000 miles in Hawai'i before we left. Our first day out, we almost got run over by a container ship outside of Waikiki because we couldn't turn the canoe around. We recognized we made some big mistakes in our computer design and took the canoe back out of the water. The hull shape and the sails were not in balance. The only way to balance them was to turn the hulls around. We took all three miles of lashings off, turned the hulls around, relashed the canoe, and then sailed it. It sailed perfectly.

The Voyage to the Marquesas-1995

The voyage to the Marquesas in 1995 was not just about Hokule'a, but also the children of Hokule'a--Hawai'iloa and a third canoe from Hawai'i called Makali'i; two canoes from Rarotonga--Te 'Au Tonga and Takitumu; and Te 'Aurere, Hector Busby's canoe from Aotearoa. We all met to Tahitian canoes--Tahiti Nui and 'A'a Kahiki Nui--at a place called Taputapuatea, on the island of Ra'iatea--a place of great teaching in navigation, the most appropriate place to start this voyage that would take these canoes to the Marquesas Islands. Some believe these islands are the homeland of the first people to come to Hawai'i.

We trained the navigators for the canoes for five years, recognizing that for our voyaging traditions to remain strong, we had to build strength in numbers. Six canoes made the voyage from the Marquesas to Hawai'i, over 2,200 miles of open ocean. Five of them were guided by navigators from their own islands, trained to sail in the ancient way. We used transponders to track the positions of the canoes for documentation and safety. We staggered the departures from the Marquesas, so that each canoe was by itself. If we were all together, one canoe would be leading, and everybody else would be following. So everybody sailed on their own. All the canoes made it to Hawai'i. The tracks of the canoes were similar--the navigational system works. But what's more interesting, to me, is that the process of education can work to accelerate learning when you combine tradition and science, and when you have people who are motivated--compassionate enough to work hard and commit themselves to as difficult a task as this voyage was.

Voyaging canoes from the South Pacific sailing in Hawaiian waters beneath Diamond Head--to me this represents the fulfillment of dreams. Not just dreams, but powerful beliefs that what you're doing is important, it's worth the commitment--even though you're risking lives. I think of Hector Busby--his vision and his commitment to his people. I've seen the struggles. This was not an easy thing to do.

Hector Busby’s Te Aurere Sailing in Mamala Bay, Honolulu

To the West Coast and Alaska-1995

After the 1995 voyage to the Marquesas, we took two of our voyaging canoes--Hokule'a and Hawai'iloa--and shipped them to Seattle. There are more Hawaiians living away from Hawai'i than live here--the majority of them on the West Coast of North America. They've made this choice for many different reasons, but if you talk to these people, many of them say that their hearts and their spirits are still in Hawai'i, their home is in Hawai'i. We couldn't bring the 185,000 people back home, but we could take our canoes there. Hokule'a sailed down the West Coast to connect with them, to build better relationships, to share ideas and educate.

Hawai'iloa went to Seattle and then north to Alaska. We visited 20 different native villages between Vancouver and Juneau. We took Hawai'iloa on this 1,000-mile journey up the coast to thank the native Alaskans for their gift of logs, and, more importantly, to let them know that we did not abuse the gift they gave us when they cut down those trees. The only way we could thank them was to take the canoe to them. We weren't giving it back. We were showing them what was already theirs. It was an incredible voyage of cultural exchange and connecting people.

Hawai‘iloa sailing in Icy Straits, on the way to Haines, Alaska

Alaska is rich in resources. It has 500 times more land than we have in Hawai'i, and only half the population. The people are very healthy because they can still sustain themselves with the resources of the place they live in. Because of my ignorance, I thought the people would be very different from us. They come from a different place and speak a different language. I was wrong.

When Hawai'iloa was leaving Hilo for the Marquesas along with Hokule'a in 1995, Judson Brown was a special guest. He was there, we thought, so that we could thank him. But he told the crowd who had gathered to see the canoes off: "I am very grateful that the Hawaiian people would thank us for what the Alaskan people have given them. But in truth, all we did was give you wood; you have given my people a dream."

Everyone was absolutely silent. Judson understood that we were building a bridge between native peoples. His role was critical, not just in getting the trees, but in the celebration of culture. Even though Hawaiians and Alaskans are different people--defined by their different environments, languages and cultures--in the end, the native Alaskans share the same kinds of concerns and hopes and aspirations as we do. They believe that it is very important for the health of their people to rebuild their culture, to rebuild their traditions.

When we went to visit Judson's home in Haines, Alaska, we were taken into a small building by a river, a simple and humble place with a wooden floor. We sat on the floor and the people gave us a potlatch. They heaped gifts before us. I was embarrassed. I saw an elderly lady sitting against the wall in the back of the room. There was a young boy with her, her grandson. Toward the end of the gift-giving, I saw her hand to him a small package. She seemed embarrassed about the gift, almost ashamed. The young boy walked quietly up to the front of the room and put the package on the pile of gifts. I saw that the package was full of hundred dollar bills. I was shocked. I turned to Judson and said, "I don't know how to respond to this kindness."

"Our idea of wealth," he told me, "is not about accumulating possessions but giving them away. We have survived for centuries by caring for our natural environment and by sharing with each other."

Judson Brown passed away in 1997 and was buried in his native village of Klukwan. He is still with us because the bridge that he built between the people of Hawaii and the people of Alaska is still strong. After Judson's death, his people carved two totem poles. They brought one to Hawai'i, with a delegation of fifty people to celebrate this connection in the Bishop Museum's Hall of Discovery. At the ceremony there was an elder, Alan Williams, who said: "We are doing this as our contribution to keeping the relationship between the Hawaiians and the Native Alaskans alive." The other totem pole is in Juneau, Alaska, and that is the other end of the bridge that will always connect the people of Hawai'i and the people of Alaska.