Voyage to Rapanui

Journal, Tahiti to Hawai‘i, February 5-27, 2000

Sam Low

Photos by Sam Low on Hokule‘a and Makanani Attwood on Kamahele

Kinohi loa

This is just the kinohi loa – the beginning - of a long voyage of words. It is dedicated to my aumakua and my kupuna and especially to my father, to Clorinda, to Pinky and Laura.

My father's ashes were laid in deep swirling pools of water in the Atlantic more than 35 years ago – blood of Hawaii nurtured by blood of New England – joined in the moana that knows no boundaries. I am two spirits – of the anuanu land, the cold place and the nopu, the hot – of the ohana of my mother and father. Their love for joins these two worlds. May this work which we take on – from the valley of Niu to the sand plains of Martha's Vineyard – strengthen that union. Aloha.

Sam Low

Departure

In the harbor - ice like pancakes. On the ship - decks rimed with salt stirred by yesterday's wind. Sloops and schooners – moored in ice - wear mustaches. Sleeping.

A longshoreman exits a building, windows sheathed in condensed warmth. “Ain't seen it like this for a long time. It's the wind chill – forty below.” Pigeons huddle on the building's roof.

Seagulls squat on lily pads of ice. The air is still. A plume of smoke rises like a white pine tree. The ship glides through slush. I slide away from one island home – to another.

A faint sun. Sky joins sea in a dull crease – a deeper band of gray – as if at the ocean's extremity the atmosphere was bent upon itself like a piece of tin. The island, receding, is dark. Then lighter. Then gone.

Blessing

The heiau browed the hill, gift of many ancient hands, strong with mana like bleached bone wrapped in tapa. The knowledge came with a price, was a gift encumbered with duty. Our navigator accepted the gift with ha'aha'a – humility. He would soon stand upon the smooth planks of the canoe – the leader of yet another seeking, accompanied by his aumakua and his ohana, his comrades entrusted to each other, sliding through danger. But first this. Alone. The request for pomaika'i – blessing – and for alaka'ina – guidance – and for koa – courage. Ancestral mana throbbed from the stones of the heiau into the soles of his feet. He stood there beneath the heiau's hooded eyes – waiting to enter.

Crews

Hokule'a: Snake Ah Hee, Chad Baybayan, Pomaikalani Bertelmann, Bruce Blankenfeld, Shantell Ching, Sam Low, Joey Mallot, Kahualaulani Mick, Ka'iulani Murphy, Kau'i Pelekane, "Tava" Teikihe'epo Taupu, Nainoa Thompson, Mike Tongg, Dr. Patrice Ming-Lei Tim Sing, Kona Woolsey. (Total: 15.)

Six Canoe Sisters (The most ever on a single Hokule'a crew): Kona Woolsey, Kau'i Pelekane, Ka'iulani Murphy, Dr. Patrice Ming-Lei Tim Sing, Pomaikalani Bertelmann, and Shantell Ching

Kama Hele: Alex and Elsa Jakubenko, Makanani Atwood (Hawai'i), Eric Deane (Tahiti), Mate Hoatua (Tahiti), Richard Konn (Tahiti), and Teikinui Tamarii (Tahiti). About the Escort Boat Kama Hele and its Owners, Alex and Elsa Jakubenko.

Click here for Sam’s Portraits of the Homebound Crew.

Tautira: Hokule'a's Home in Tahiti

I first visited Pape'ete in 1966 when it was a somnolent seaside town with a few yachts tied to the quay along the main street. There were low buildings along the street and a famous bar, called Quinns, which had a rough reputation. Today, few places are left from that earlier time. There are the grand avenues where the old French Colonial buildings still stand and the Hotel Royal Pape'ete which was once the best but is now overshadowed by many new ones on the city's outskirts. Office buildings rise above boutiques and restaurants. The bars are fancy in the French manner, which means expensive and with an "I could care less" attitude which passes for an island weltzschmertz.

The Banyan trees that I remember still cast pools of shade along the park beside the main street and locals with tattoos still sit under them watching life pass and talking in a mix of Tahitian and French. The popping of motor scooters is familiar but it's now drowned by the roar of big diesel tourist busses and Mercedes trucks and the street is clouded with fumes. Pape'ete has become a place that, if you know better, you leave as soon as possible.

Hokule'a's home port in Tahitian waters is the village of Tautira, an hour's drive on a road that winds through a landscape of utilitarian architecture - burgeoning strip malls, gas stations, lotissemonts - a French-Polynesian version of suburban sprawl. Following the road, the hubbub of uncontrolled development subsides. The air clears of fumes. Mountain peaks jostle toward the shore - presenting waterfalls and vistas into deep valleys. In Tautira, the road ends.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited Tautira in 1888 on a cruise through the South Seas . "One November night in the village of Tautira ," he wrote to a friend, "we sat at the high table in the hall of assembly, hearing the natives sing. It was dark in the hall, and very warm; though at times the land wind blew a little shrewdly through the chinks, and at times, through the larger openings, we could see the moonlight on the lawn... You are to conceive us, therefore, in strange circumstances and very pleasing; in a strange land and climate, the most beautiful on earth; surrounded by a foreign race that all travelers have agreed to be the most engaging... We came forth again at last, in a cloudy moonlight, on the forest lawn which is the street of Tautira. The Pacific roared outside upon the reef. Here and there one of the scattered palm-built lodges shone out under the shadow of the wood, the lamplight bursting through the crannies of the wall."

Tautira has changed since then, of course. The "palm-built lodges" are long gone, replaced by neat bungalows of wood or cinderblock with metal roofs. But the mountains of the Vaitepiha Valley still rise above the village and the Pacific still roars upon the reef and the swells still make a solid white line on an azure gin-clear sea. In the lagoon it is calm. There are stands of tall coconut palm along the shore along with ironwood, milo, mango and ulu trees with leaves that open like human hands, yellow in the palm, dark green at the finger tips. Small fishing skiffs are parked in many lawns. There is a public water tap by the Mairie - the Mayor's office - and many village women come here to wash their clothes; hanging them out to dry in the yard - pareos of many colors and designs. Driving into the village, the valley opens wide, revealing peaks deep inside, masked in cloud. The slopes are light green with ferns. Mango trees stand above the ferns and lower down are hala trees in groves. Tautira remains, as Stevenson wrote more than a hundred years ago, "a strange land and climate, the most beautiful on earth."

Nainoa Thompson first visited Tautira in 1976 as a crewmember aboard Hokule'a. There he met Puaniho Tauotaha, one of the village elders - a fisherman, canoe paddler, and canoe carver - a man of immense physical and spiritual strength.

"You could be in the canoe house," Nainoa remembers, "and there was laughter and singing and people talking but when Puaniho got up to speak there was complete silence. I didn't know what he was saying but it felt like an oration. And if he wasn't doing that he never said anything. When he coached the canoe paddlers he hardly said a word. He was an extremely quiet man. Very religious, very disciplined. He was the edge of the old times."

After her famous maiden voyage to Tahiti, Hokule'a sailed from village to village along the coast. Wherever she stopped, the crew was hosted like visiting royalty. Nainoa had yet to sail aboard the canoe on a long voyage and although he had prepared for the return trip he was nervous and he was embarrassed by the attention.

"We would prance into these parties and sit down and they would feed us food and beer all night as if we were very special people - which we were not," he remembers. "We sailed into Tautira, the last stop in Tahiti , and we anchored and I had just had enough. I told Kawika, the captain, 'I will stay aboard the canoe.' The current was strong. We had two anchors and the bottom was coral and they were not going to hold well so I was worried. 'We are so close to leaving,' I thought, 'what if the anchors drag and we damage the canoe?'"

Kawika agreed that Nainoa could stay aboard while the rest of the crew went to the party in the village. That afternoon, Nainoa enjoyed the solitude. The canoe bobbed serenely at her anchorage. The sun began to settle over the nearby mountains.

"Finally, the sun went down behind Tahiti Nui," Nainoa remembers, "and I saw this little girl, maybe four or five years old, on the beach. She had a flower in her ear and she was waving to me to come on shore. She just kept on waving. So I went on shore and she grabbed me with hands so small that she could hold just two of my fingers. She took me by the hand and led me down the road and into a simple house with a dirt floor. They had put in some picnic tables and they had the whole crew in there and they were feeding them shrimp and steak and all kinds of food. Somebody would stand behind you and if your beer glass got half empty they would fill it up. Puaniho came in. He was the stroker for the old time canoe paddlers. He sat down. He had powerful eyes. He was poor in material things but he was a very strong and powerful man. He couldn't speak English and I couldn't speak French or Tahitian. We sat there and we spent the evening with him. It was just overwhelming how much the people of the village give when they had so little to give. They didn't have a floor in their house, much less beer and steak to share. I felt awkward. Here was this Hawaiian group who really didn't know a damn thing about sailing and they were treating us as if we were special people."

"We sailed back to Pape'ete and we were staying in a hostel," Nainoa continues. "Two days before we left I was sleeping in my room and about four o'clock in the morning I woke up. Puaniho's wife was pulling me by my toes and waving to me to go outside. So I got my clothes on and we went outside. She couldn't speak any English and so she just signaled to get in her truck. We drove all the way back to Tautira, early in the morning, as the sun came up. We went to every house, every house, and we stopped and they filled that truck up with food. By the time we drove back to Pape'ete I was sitting on a mound of food - banana, taro, mango, uru - everything. There was no verbal communication. Puaniho drove right up to the canoe. He knew exactly what he was going to do. They put all the food aboard and then he drove off."

"Somehow Puaniho knew that I was nervous about the trip. I was even considering not going. The next day he came back and he had carved a wooden cross, a necklace, and he gave it to me. That was when I knew that I had to go."

When Nainoa returned to Hawai'i aboard Hokule'a in 1976, he told his grandmother, Clorinda Lucas, and his parents, Pinky and Laura Thompson about Puaniho and the hospitality the crew had received in Tautira.

"I told that story to my grandmother and to my mom and dad and you can imagine what that meant to them. They knew that I was afraid - that I felt that I was not prepared. And these Tahitians knew what to do to care for me and the crew by giving us what they could - their food and their aloha."

In 1977, Nainoa invited Tautira's Maire Nui Canoe Club to Hawai'i to compete in the Moloka'i Race. About fifty people arrived. Pinky and Laura moved out of their home in the Niu Valley as did Nainoa and his sister Lita and her husband Bruce Blankenfeld. They converted the Hui Nalu canoe shed into a dormitory with bunk beds on loan from the National Guard. For a month Nainoa and his family hosted their Tahitian guests. It was the beginning of many such exchanges between the people of Hawaii and Tautira.

Maire Nui won the race. "All the other crews were competing for second place," Nainoa remembers. They returned twice more, winning each time, and retired the famous Outrigger Canoe Club cup which now sits in the house of Sane Matehau Salmon - Hokule'a's host whenever she visits Tautira.

"If you understand how anxious my parents and grandmother were during the 1976 voyage, you can understand how grateful they were for the hospitality shown to us by the people of Tautira. And you can understand how they would move out of their house and give it to them and feed them for a month. That's why Sane says 'This we will never forget and this is why we will always take care of you when you visit Tahiti .' And then you can also understand why Hokule'a has to come back to Tautira whenever we come to Tahiti ."

"For me, Tautira is not just a beautiful physical place. It's a symbol for the kinds of values that are important," Nainoa says. "I learned from the people of Tautira that there are other ways to measure wealth besides the things that you accumulate. The people of Tautira are extremely happy when they see that we are happy. When they give to you they feel rich themselves. That is what Tautira is all about.”

Thursday, January 27, 2000

It's simmering in the flat skirt of land beneath Tautira's towering peaks. Crevices etched in the peaks by rainy season waterfalls are dry. The lagoon is a mirror and the surf is a light scrim lining the reef. Puffy cumulus clouds crenellate the horizon as cirrus and mare's tails glide almost imperceptibly overhead. There's not a breath of wind.

In the morning, we receive flu shots from doctor Ming-Lei Tim Sing and Kaui Pelekane, a nurse at Queen's Hospital in Honolulu .

Chad Baybayan presides at our first meeting as a crew.

“Have all the halyards been checked for wear and replaces where necessary?” he asks Kamaki Worthington, a crew member on the voyage to Rapa Nui who remained in Tahiti to care for the canoe.

“The halyards are done,” Kamaki says, “and the sails are tied on and ready. The number twenty-nine is on the fore mast and the thirty-two is on the mizzen.”

“How about the radios?”

“The handhelds work fine and we tested the transponders and the single sideband.”

The transponder is a radio transmitter that sends a signal to Honolulu via satellite where it is decoded at the University of Hawaii to provide a record of Hokule'a's track across the ocean.

“Good work,” says Chad .

“Mike and Kahua will check out the radios today,” he continues, assigning each of us our tasks, “and call PSAT this morning.”

“Ka'iulani and I will make sure the water is loaded aboard.”

“Sam, you inventory the documentation gear.”

“Bruce and Snake, you check the fishing equipment. Pomai and Terry will check the galley, and Bruce – can you make a list of the fresh food we'll have to take aboard?”

Whenever Hokule'a arrives in Tautira, her crew is fed and housed by the villagers, with assignments arranged by Sane Matehau, mayor for the last 23 years and a prosperous building contractor. Sane appears to be in his early fifties. He is a physically strong man, barrel-chested, with a round open face that is often creased with pleasure. He wears his hair in a modified brush cut. His girth is ample. He is a man who naturally commands attention. Sane has six brothers and three sisters - a huge family that has become our ‘ohana in Tautira.

Our Tautira Hosts

- Edmon and Lurline – Shantell, Sam and Pomai

- Vaihirua – Maka

- Tepe'a and Toimata – Bruce

- Ota and Terrevarua – Tava, Kamaki and Chad

- Sikke and Linda Matehau - Mailing and Kona

- Franco and Laiza Toofa – Kaui Pelekane

- Jaqueline and Sabu – Marco

- Sylvain and Lydia Atchong – Terry

- Mereille and Manuia Marutaata – Ka'iulani

- Maeva and Patrice Taerea – Nainoa and Pinky

- Rosedine and Gerrard Mana - Joey

Friday, January 28

We continue to prepare for sea. During the morning crew meeting, Nainoa asks us to have the canoe ready to depart on three hours notice beginning tomorrow. The wind has been light and northerly but if it shifts back to trades from the southeast, we must be ready to take advantage of it.

“Our main problem is to get north beyond the Tuamotus,” he tells us, "and that's about 240 miles. So if the wind shifts we've got to go."

The Tuamotus screen our course to Hawaii . Sometimes called "the dangerous islands," they are low coral atolls - difficult to see during the day and almost impossible to see at night - although Master Navigator Mau Piailug can smell their coconut palms many miles at sea. The islands are a blessing for canoes sailing from Hawaii to Tahiti because they provide a 405 mile long "safety net" across the canoe's path - a large area of land and bird signs that extends the geography of landfall. But sailing back to Hawai'i they're a barrier to the open ocean which must be passed before a navigator can breathe freely.

With the wind on our beam - from the east - we can sail through the Tuamotus quickly, but when it's from the north, as it is today, we must tack - extending the time we are among the low coral atolls - and the danger.

As we wait for favorable winds, hundreds of chores are completed - life jackets, harnesses and flashlights are distributed to the crew; strobe lights, and man overboard gear is checked; electrical equipment - radios, satellite transponders, solar panels and batteries – is tested; galley gear is loaded aboard.

Tomorrow the vigil begins. The navigators will scan the skies for signs of easterly winds while we await the word to depart. Our duffel bags are packed.

January 27 - Meeting at the Mayor's Office "The Old Men of Tautira"

You could imagine a meeting like this in a thatch-roofed canoe house hundreds of years ago with the visitors' double-hull voyaging canoe drawn up on the beach outside. But this meeting is held in the white-washed conference room of Tautira's mayor - Sane Matehau - and the date is January 27th, the year 2000. Only the feeling is ancient - a sharing of stories by friends from distant islands, a bonding together of a wide-spread `ohana.

Outside the conference room, the setting sun colors clouds over nearby mountains and a cool wind washes ashore over the reef. Inside, we are seated in a circle with representatives of Tautira's community, including Kahu from the Protestant, Catholic and Mormon churches. Sane has called the gathering to celebrate the 25 th anniversary of the joining of Tautira's people with the people of Hawai`i .

The first to speak is Tutaha Salmon. For a Tahitian, he appears almost delicate, yet his bearing is dignified, suggesting confidence. His graying hair indicates he may be in his seventies. Tutaha was once the mayor of Tautira – a position now held by Sane - his son-in-law. He is now the governor of a large Tahitiian district including Tautira and three other towns: Faaone, Taravao and Pueu.

"It's an honor that whenever Hokule`a sails to Tahiti she lands here in Tautira," Tutaha tells us. "How many times have you come? I cannot count them. But what's important is that you are now our family - our brothers and sisters."

Following protocol that is ancient, Tutaha then speaks of his elders. The enfolding story of Hokule`a's relationship with Tautira began with "the old men" - a six-man canoe team who paddled their way into the history books

"Our dream of cultural exchange was born twenty-five years ago. In those days the man I remember first is Puaniho. He has now passed on but he showed us the way. He was a quiet man, but powerful. There was Mate Hoatua the steersman on the canoe from Haleolono to Waikiki . He steered the whole way, without relief. Henere, Tevae, Nanua and Vahirua paddled the canoe. We called them "the old men" because their minimum age was fifty. This is our time to remember them and to tie that rope tight to the mast."

"The old men" of Tautira's Maire Nui canoe club first traveled to Hawai`i in 1975 to compete in the Moloka`i race. Pinky Thompson next rose to speak in response to Tutaha's welcome.

"I want you to know that we feel at home ever since you took a strange looking Hawaiian youth into your homes 25 years ago, my son Nainoa. You recognized immediately that he was a stranger in a land that was strange to him and you malama-ed [took care of] him."

Nainoa came to Tautira in 19[76] as a member of Hokule`a's crew. He recognized immediately that the "old men" of Maire nui paddled differently than any team in Hawai`i.

"They were so smooth," Nainoa recalls, "their movements were fluid, no lost energy, and their canoe seemed to leap forward - faster than anything I had every seen.”

He wanted to learn from them and in 1977 he got the chance. In that year's Moloka`i race, Nainoa's team from Hui Nalu lined up next to "the old men."

"They were twice our age, and we were a pretty strong crew but they left us in their wake, paddling easily."

In that same year, Nainoa traveled to Marina del Rey to serve on a motor boat escorting Maire Nui in the Race to Newport Beach , California.

"They finished the race, took a shower, and were drinking a beer before the second place canoe arrived. They beat them by an hour and 4 minutes."

Nainoa invited Maire Nui to stay in Niu Valley when they came to Hawai`i in 1978 for the Moloka`i race and again in 1979 when they won the koa division for the third consecutive time – retiring the famous Outrigger Canoe Club cup to an exhibit case at Sane Matehau's home in Tautira. Over the years, visits by Maire Nui to Hawai`i and by Hawaiians to Tahiti continued. Puaniho built a Koa canoe for Hui Nalu and later another famous Tautira canoe builder flew to Kona to build six Koa canoes - helping to inspire a renewal in traditional canoe building that thrives today.

Nainoa, Bruce, Pinky and their Hui Nalu colleagues studied the Tahitian way of paddling and became champions themselves. Pinky remembered those moments in his presentation at the Mayor's office.

"You helped us become champion paddlers, but you did much more than that. You helped us to return pride to our Polynesian people by restoring our native craft of canoe building and paddling."

"'The old men' taught us what it means to be champs,” Nainoa added. “It's not about outward appearance. It's about what happens inside. They didn't talk much because they knew that the mana comes from within. They didn't think of themselves representing just a club - they represented all their people.”

Friday, January 28 – Crew Briefing

“We're on three hour call to set sail,” Nainoa tells us at this morning's crew briefing. “Our first problem will be to get to the Tuamotus, 240 miles to the northeast. The crew is made up of new sailors and expert sailors. It's designed that way. Bruce and Chad are in overall charge of safety and of educating the new crew. They will stand six-hour watches each – six on and six off. They will hot bunk with each other, share the same puka, because when one is sleeping the other will be on watch. Tava, Snake and Mike will be watch captains. Shantell will navigate and so she will be up most of the time. Ka'iulani and Kahualaulani will assist her so they will stand 6 hour watches, on and off. Pomai will cook, so she'll not stand a watch. The rest of you will be on watch for 4 hours, then have 8 hours off.”

On one of the long tables at Sane's house, where we eat every morning and evening, Nainoa spreads a map of the Pacific. He traces his finger along a red line drawn on the map from Tahiti to the Big Island .

“This is our course line. It's been drawn like this ever since 1980. Makatea, here, and Rangiroa and Tikihau, here, will be stepping-stones as we head north. Once we clear the Tuamotus we will sail on long tacks, hopefully one single tack, to this point 275 miles west of the Big Island , where we will turn to sail downwind, probably to Hilo . With the new sails we have now we should be able to sail efficiently. I think it will take about 22 days.”

“Our problem now is the weather. Normal trade winds, from the east or southeast, are ideal. Hokule'a can point six houses into the wind, so we can sail north or northeast. But the forecasts are now calling for winds from the north and in those conditions here's what happens.”

Nainoa takes two pencils and joins them together at the ends, the lead tips pointing outward. He arranges them in a fan with the included angle equal to six houses - 67 and a half degrees – the angle that Hokule'a can make when sailing into the wind. He lays the pencils up against the chart with the right hand pencil heading north, into the wind, and the left hand one – our course in a northerly wind – pointing off to the northwest.

“If the wind forces us to sail off to the northwest, we'll end up in Satawal.”

“The weather pattern in the Pacific at this time of the year extends over an area 5000 miles long. Since December, the Pacific (mid Pacific?) has been a convective factory of rising air. There's a large high-pressure system to the east. In the winter, the high-pressure systems move, but now they stall and another has formed to the west. In between the two systems there's a depression – a trough that extends south of Tahiti and to the west across the Pacific. It's a doldrum condition caused by two stationary air masses. A whole Pacific-wide system. That trough (which causes the north winds?) extends for a long, long way. If we set out now and sail to the northwest, we'll never get out of it. That system may be here for a long time. We're stuck.”

“There's a hurricane to the north of New Zealand , 2000 miles away, but there's no real chance that it will come up here. The hurricane is a refrigerator. It sucks out warm winds so it might allow the trades to reestablish themselves. If that happens we might get a single day of good sailing weather. But don't count on it.”

“So we have a big challenge. We have light winds but they're blowing from the direction we want to go – right in our face. To get out of here, we may have to tow. No one likes to tow, but we may have no other choice. Our voyage has a larger intent – we sail to serve our community – and we have to be back in time to get the canoe ready for her birthday at Kualoa on March 12 th . We cannot wait beyond the 5 th of February to leave, even if we have to tow. About 240 miles north of Manihi we can get into good trade winds.

Nainoa pauses, for a moment, allowing this to sink in.

“Okay, Chad and Bruce, you are in charge of seeing that the canoe is ready and conducting safety drills. But remember; be careful of the heat. You can easily dehydrate.”

(Check all of the above weather analysis with Nainoa)

Saturday, January 29 - Weather Watch

The ocean remains unsullied. Parapets of cumulus cloud are stalled around the horizon. There's a breath, and no more than that, of wind - but it's out of the north, so getting to the Tuamotus will be an ordeal of constant tacking into headwinds.

The high-pressure(?) ridge containing light unstable winds continues to dominate our weather system. We want the ridge to move but it's blocked by a zone of low pressure to the south, which pulls the wind toward it, creating northerlies. This morning Nainoa speaks with Bernie Kilonsky at the University of Hawai`i . The low may finally move south, Bernie tells him, allowing the high pressure ridge to move with it. If so, the light and variable northerlies should be replaced by easterly trades. We may see some change on Sunday and certainly by Monday. And, if Bernie is right, the trades should fill back in by Tuesday.

"Ok," says Nainoa, "we stay on alert to go within three hours notice - but if Bernie is correct we'll probably not leave until Tuesday."

In the meantime, Nainoa and Shantell Ching join with student navigators Kahualaulani Mick and Ka`iulani Murphy to lay out their course line to Hawai`i and discuss alternative routes depending on changeable wind and weather conditions. Bending over the kitchen table in Nainoa's house, they first consider the effect of the current.

"The longer you're in the current the more its effect will be," Nainoa explains, reviewing basic knowledge, "so the amount of offset will depend on your speed. The slower you go - the more the offset."

The offset is also affected by the angle that the canoe makes to the current. Assuming the canoe's speed to be five knots, for example, with an easterly current of half a knot, a heading of Manu (NE) will produce an offset to the west of four degrees. Increasing the canoe's angle to the current increases the offset. If she heads Nalani (NE by N) the offset is five degrees, while a course to the north (Akau) means an offset of six degrees. This kind of effect becomes great over long distances. Consider the passage from Rangiroa to the doldrums, about 1100 miles. At a speed of 5 knots, a half knot easterly current will set the canoe to the west 12 miles a day or 108 miles during the nine day voyage.

The navigators memorize current effects like these as a set of general principles which can be easily modified mentally as conditions change. If they sail north at 5 knots and the current is from the east at half a knot - the westerly offset is 12 miles each day. Change the canoes speed by 50% to 2.5 knots and the daily offset will be twice as much - or 24 miles – because the canoe will take twice as long to cover the same distance.

"We always try to eliminate having to do math in our heads," Nainoa explains, "it can cause serious brain damage."

For now, the navigators concentrate on the "first stage" of the voyage home - from Tahiti to just north of Rangiroa - when the canoe will enter the open ocean and begin "stage two" to the doldrums. During the first stage, Makatea - about 124 miles to the north - will be a stepping stone, a chance for Shantell and her colleagues to test the accuracy of their navigation. They consider when to depart Tautira in order to arrive at Makatea with sufficient time to explore the island.

They decide to leave at 11 am . They will have no celestial bodies to steer by so they must guide the canoe by "back sighting" on Tautira's mountain peaks. Shantell figures they will be able to use the 4,500' high mountains for about 60 miles on a clear day and maybe 30 on a humid day - like today.

"That means that if we sail at five knots we can use our back sight for about 6 hours," she says, "or until 5 p.m. By 3 p.m. the sun will be low enough on the horizon to steer by so we can check our course to Makatea and modify it if necessary."

When they reach Makatea, the navigators must decide when to set out for the difficult pass between the low coral atoll of Tikehau and Rangiroa which leads out into the open ocean. Kahualaulani runs his finger over the eastern side of Tikihau's fringing reef.

"These black marks are coconut trees," he says "and we should be able to see them maybe ten miles at sea - during the day. At night, forget about it. We might be right on top of the reef before we see it."

"The distance from Makatea to Tikehau is 40 miles," says Shantell "and we want to be no closer than 10 miles at sunrise, so when should we leave?"

"If we can average five knots then we should leave about midnight ," says Ka`iulani, "which should get us to a point about ten miles off the reef at about 6 a.m. "

And so it goes - the three navigators bend over their charts, discuss strategy, and make notes in their logbooks. From time to time, Nainoa joins them, asking questions - probing their readiness.

"I may be asking a lot of questions of you guys now," he says, "but at sea I'm going to back off. We'll meet at sunrise and sunset and talk about where you think you are and what course we should steer, but I will only step in if you're about to make a mistake that will jeopardize our safety."

The navigators' meeting breaks up at about noon but they will meet again at sunset to watch the stars rise over Tautira's peaks and establish their "back sight." The rest of us wait impatiently to board the canoe and leave - but for them the voyage has already begun.

Sunday, January 30

For the crews of Kamahele and Hokule`a, including new arrival Nalani Wilson, today was mainly one of rest. The weather continues unchanged - hot, humid with little wind - although it was cooler last night. At 4 a.m. this morning Ota, Sabu, Papa Vaihiroa and Tepea began preparing the imu for what may be our last big feast in Tautira before departing. At one p.m. , we gathered at Sane's to pule, then dig into roast pork, fish, taro, breadfruit and all the traditional dressings - a grand Tahitian feast. And singing, lots of singing.

January 31, Monday - Wind Watch

At 5:30 a.m. Shantell and Pomai Bertelmann stand at the end of the jetty leading into Tautira's harbor. They see the dark outline of mountain peaks descend to the sea - punctuated by upthrusting coconut palms at the shore. They see an upturned scimitar of moon, pale against the brightening sky, and the bright spot that is Venus. More importantly, they see a broken rope of compressed ropy cumulus clouds trailing away to sea from the mountains' dark slopes.

"There's wind out there," Shantell says, "and it looks like light trades. The clouds are dispersed on the horizon which means the wind is light, it's not strong enough to push them together, but it's there alright."

Ripples flit across the surface of the lagoon - fanning away from the beach - the result of wind funneling through deep valleys behind Tautira.

"That's a local wind," Pomai says, "which is apparently from the south, but it's not significant."

Cars and bicyclists begin to move through the village. A group of children, bearing baguettes, walk by. The sun rises orange behind the low scudding clouds and the clouds lighten and pick up the sun's orange glow. High cirrus clouds are brush strokes of yellow and white.

After breakfast, we meet aboard Hokule`a where Nainoa , Chad and Bruce assign each of us watches and duties while underway. The canoe is moored in the sheltered lagoon. There's no breeze and it's already extremely hot. Snake, Mike and Tava - the three Watch Captains - take us through drills. We open and close the sails and practice bending different jibs on the forestay. We rig a larger mizzen sail in anticipation of light winds. As a final drill, and without warning, Bruce yells "man overboard" which elicits a scurry to pull in the sails, douse the jib, deploy the man overboard pole and make radio contact with the imaginary escort boat ghosting in our wake.

"Good job," is Bruce's comment.

By 2 p.m. , the low ropy cumulus clouds have morphed into puffy ragged shapes - an N.C. Weyeth sky - with exuberant parapets of cloud marching briskly from east to west. Palm fronds clack together in the freshening breeze. Nainoa spreads the word - if the winds continue to build, we may depart tomorrow morning.

In the afternoon, Shantell and the student navigators gather with Nainoa. They discuss the weather. “When you look at the clouds and see that the bases are all at the same level over the horizon, then you can predict that there is wind out there.” says Nainoa. “If you see high clouds with a lot of vertical development, the winds are slowing down. But you can be fooled. During a hot day like this morning, the land heats up and the cool air over the water tends to flow toward the land – a convection effect – and that makes it appear that there may be strong trade winds. But if the wind comes out of the valleys at night, you know that it's not trades.”

“This morning it looked like we might have light trades,” says Shantell, “but in the afternoon when I was at Sane's the clouds started to get more vertical.”

“And wisps of cirrus,” says Nainoa. “When rain squalls develop vertically the rain pulls down the moisture and leaves cirrus behind. The wind regime is still very light. We have to wait until tomorrow to see what develops.”

“The trip to Rapa Nui required that I be able to focus and to use my instinct much more than my intellect,” Nainoa says. “We sailed on even when there were no stars. We were pushing every inch of the way to stay ahead of a front behind us. That was a trip that I knew my intellect would not get us through, so for this voyage I'm paying more attention to the other side.”

The navigators focus on the upcoming voyage to Makatea. (Check this) “Makatea is 65 degrees from Tautira,” says Shantell, “ so if you factor in 5 degrees of lee drift and 5 degrees of current at 5 knots (the current or speed of canoe?) we want to point the canoe one house upwind of the current. We want to steer Nalani.”

“What is the estimated time of departure out of Tautira to get to Makatea based on a canoe speed of three knots?” Nainoa asks. “Keep in mind that we can see about 21 miles on a light wind day because there's no salt in the air.”

“At one a.m. on Wednesday,” says Shantell.

“So we would be at Makatea at 6 p.m. , that's ugly.”

“How long would it take if we can sail at 4 knots?”

“Thirty-one hours.”

“So when do we leave?”

“ Eleven a.m. ” (I don't think this is right. If takes 41 hours at 3 knots and 31 hours at 4 knots, the difference in time to leave is 10 hours, so 6pm minus 10 hours = 9AM?)

“Yes, so we need a wind that will allow us to sail at about 4 knots. If our speed parameter is 4 knots, we won't leave tomorrow. Let's shoot for Wednesday and better winds.”

“If we want to stop ten miles short of Tikihau at night, do we wait at Makatea or de we leave and wait at Rangiroa?” Kahualaulani asks.

“If the winds are from the east we go and wait at Rangiroa. If they are behind us – no. The wind will tend to blow us onto the islands.”

“Tikihau is hard to see,” says Shantell. “When we went there in '95, it took me a long time before I could see the trees.”

“I want to sail home,” says Nainoa at the close of the meeting, “because only through sailing can we learn. It's the relationship between us and the canoe and nature that I want, so I'm opposed to towing because that allows us to artificially set our speed and we don't learn.”

At the end of the day, we fan out to our homes to wash clothes, write in our journals and prepare for departure. Shantell Ching lays out her star charts on the long dining table at Sane's house and immerses herself once again in the intricate details of navigating Hokule`a home.

Tuesday, February 1 - No Wind

At 5 a.m. , when the village first begins to stir, the lagoon is calm. Palm fronds are motionless. The air is still. It appears that yesterday's cloud messengers and their rumor of trade winds was a ruse. Last night, downpours cleaned the sky, opening a view to brilliant stars - Orion (ka heihei o na keiki), Taurus (kapuahi) and the Pleiades (makali'i) - a virtual explosion of tiny, blinking points of light. This morning it is, once again, much too tranquil for our tastes.

At last night's navigator's meeting, Nainoa discussed the French weather predictions, courtesy of Guy Raoul – our meteorological guru in Mangareva. Today - winds ESE at ten knots; tomorrow - ESE at 5 knots, Thursday - ESE at 10 knots and Friday - variable. The direction of the wind is favorable but its velocity is not. In ten knots of wind, the canoe - heavily loaded as she will be at the beginning our voyage – can make maybe three knots. In a five knot zephyr, she will bob and rock – almost stalled. We decide to wait for the weather pattern to reveal itself. But deadlines are approaching - Hokule`a's March 12th birthday celebration at Kualoa, for example. Nainoa's guesses that if the winds do not become favorable by Saturday, we will be forced to depart Tautira under tow. To prepare for that, and be ready to leave on short notice, Alex and Elsa Jakubenko will depart Mo'orea, where they've been visiting with their family, to arrive here tomorrow aboard Kama Hele.

Today, the crew gathers at the canoe to load fresh produce. Over the rail, gifts from the people of Tautiura, come bananas, mango, limes, coconuts, vi (a mango-like fruit), grapefruits... We stow onions and ginger in netting along the port and starboard navigators' platforms. Pomaika`i Bertelmann and Dr. Ming-Lei Tim Sing check out the galley - a two burner propane stove in a fiberglass box on deck - and inventory basic staples.

Ming and Pomai at the galley

Mike Tongg briefs us on radio procedures.

Mike

Joey Mallot, Kaui Pelekane, Kona Woolsey and Snake Ah Hee lash spare booms along the port and starboard catwalks.

At six thirty p.m. we meet aboard the canoe. Nainoa tells us we may depart tomorrow if the wind shifts, but more likely on Thursday. The latest weather reports from both French and American meteorologists agree that the wind north of Rangiroa, beginning on Saturday, is likely to be 20 knots out of the east - reason enough, he explains, to leave on Thursday even if at the end of Kama Hele's towline. A Thursday departure will also give the navigators some moonlight when we reach the vicinity of Hawaii so they may see the nighttime horizon and more easily judge a star's altitude - the key to latitude.

“If we wait here too long,” says Nainoa, “the moon will be too small to see the horizon. We want to be in the latitude of Hawaii on the 25 th when the moon will be up at 11:30 .”

And when we reach three degrees north - the usual address of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (the doldrums) - the moon should be full, a guide to direction even under heavily occluded skies.

"But right now there is no convergence zone," Nainoa tell us, “because the low to the South is pulling the southeast trades around more to the east.”

The convergence zone is usually marked by the meeting of two massive wind belts--the NE and SE trades--in a broad zone near the planet's belt tine--the equator. But partially because of the effect of the low to the south--pulling the winds down to it--there is virtually no convergence. To the north of Rangiroa we should encounter steady easterly winds to power us all the way to Hawaiian landfall.

Wednesday, February 02, 2000

Dogs sleeping in the shade of their houses, pant rhythmically. Even at complete rest, under the tents that shade Hokule`a's decks, sweat sheens the skin of her crew and darkens their tee shirts. Chad runs an abbreviated meeting--explaining that we plan to raise anchor tomorrow morning and move to a pier near to Tautira's school where prior to departure, we will invite the children aboard and, later perhaps, the families who have so generously hosted us. At the conclusion of simple departure ceremonies we will set out for home--given, of course, that all these plans ultimately depend on the weather and other variables not under human control.

At nine a.m., precisely on schedule, Kama Hele glides through the entrance to Tautira's fringing reef and drops anchor a few hundred yards from Hokule`a. Maka welcomes her with warbling blasts from his pu. With Kama Hele's arrival it seems like now, finally, all is ready for our departure.

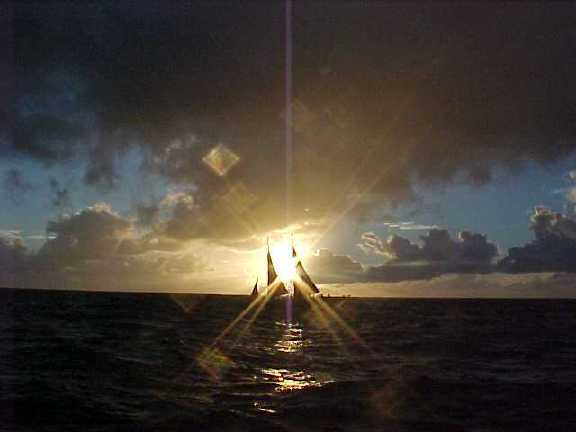

Thursday, Feb. 3 Sunrise/Tautira

The white "bread truck" threads its way through the streets of Tautira, honking its horn. Women emerge from trim bungalow or ranch-style houses, cross lawns rimmed by hibiscus, and take delivery of slim baguettes-the Tahitian breakfast staple. There are puddles in potholes where roads are dirt-evidence of another early morning downpour. At the thin strand of the beach near Tautira's man-made boat harbor Nainoa, Bruce, Chad and Shantell gather once again to study the clouds at sunset. "What do you see, Shantell?" Nainoa asks after another group has had time to assess the evidence of weather presented by the brightening skyline.

"The clouds are towering," she says, "so the wind is light."

"What direction?" Nainoa asks.

"If you face North I can see the clouds moving," she says, "so the direction is probably northeast."

"Right, but slow, yeah?"

"Yes," Shantell agrees.

The light northeast winds will make it difficult for the canoe to make any progress toward Makatea--her first landfall after Tahiti. The navigators huddle to discuss the situation. The rising sun disappears behind a dark smudge of cloud and sends spears of light down to meet the rippled water of the lagoon. A fishing boat exits the harbor and picks up speed, heading east.

"I feel the pressure of our schedule to return to Hawaii," Nainoa says, "but the wind is light, we might not be able to make it to Makatea. We should think of what is best for the experience of the young navigators and the canoe. My instinct-from having watched the changes since Sunday-is that the wind will continue to get better. "Mau always taught me that you don't decide when to go, the weather tells you when you go, so I think we wait."

So we will not depart today for Hawaii but neither will we be idle. Hokule'a and Kamahele will weigh anchor to move over to a place near Tautira's school for an educational session and then set sail for a few hours to provide a Bishop Museum/Olelo film crew an opportunity to gather video material for an educational program. Then, in the afternoon, canoe and escort will return to their moorings to await a favorable wind shift. We are disappointed not to be on our way but, at the same time, glad for the opportunity to spend one more day with our Tahitian families.

Feb. 4, 2000--Lessons in Navigation

For the last week, Hokule`a's student navigators--Shantell Ching (the principal navigator) and Ka`iulani Murphy and Kahualaulani Mick (apprentice navigators)--have been meeting with Nainoa at his house in Tautira village. The meetings are designed to be collegial but the distance between the teacher and the students, even though they are the best of friends, is often apparent.

Nainoa, Shantell, Ka'iulani, and Kahualaulani Plotting the Course to Hawai'i

Much of the teaching comes in general principles presented by Nainoa through questions--like this one: "Suppose you think that you are 9 degrees South by your dead reckoning and you measure Kochab cross the meridian 6 degrees above the horizon--where are you?"

The students knew that a meridian altitude of 6 degrees translates to a latitude of 10 degrees South and they understand that Nainoa is asking them which method of determining their position should take precedence--dead reckoning or star sights? Are they at 9 degrees South as determined by their dead reckoning or 10 degrees South as determined by the altitude of Kochab?

There is a long silence--eventually Nainoa breaks it.

"When you get a good star measurement I'd trust it. Start your dead reckoning from the point indicated by the stars--in this case 10 degrees South."

"Here's another question," Nainoa says "Can you use Kochab as a latitude star even if it does not cross the meridian?"

Normally, the altitude of a star is taken when it does cross the meridian when it reaches its highest or lowest point as it circles the celestial poles to estimate the latitude at which the canoe is at. Unfortunately, during the first few weeks of our voyage, Kochab, a latitude star, will cross the meridian at its highest point after the sun has risen so it cannot be observed at that time. On February 5th, for example, Kochab's meridian crossing is at 6 a.m. or 0600 as sailors like to say it.

The Little Dipper, with Kochab as it brightest star, circles Hokupa‘a, the North Star in Hawai‘i. Kochab crosses above and below Hokupa‘a. On the way to Hawai‘i from Tahiti, with Hokupea‘a below the horizon, Kochab crosses the meridian at its highest point and is visible just above the horizon (and higher and higher each night as the canoe sails north, a clue to latitude.

Using a computer program that replicates the motion of the stars across the night sky as well as during long sessions with Will Kyselka in Bishop Museum's Planetarium--Nainoa watched Kochab cross the meridian time and time again. In this way he repeated the process used by ancient navigators--years of patient observation--but he was able, with the use of modern technology, to speed it up. He carefully measured the altitude of Kochab at meridian crossing and an hour before it crossed the meridian and found that the difference in altitude was only a quarter of a degree. "And that's not measurable with the naked eye," Nainoa says, "so yeah, you can easily use Kochab at 5 a.m. to get latitude."

Next, Nainoa steps through a series of more simple problems. When, for example, is it best to hold navigational meetings at sea to assess our position? At sunrise and sunset because without clocks these are easily observable times of the day.

What to do if sailing into the wind and inexperienced helmsmen are having trouble steering an accurate course? Trim the sails and move weight around on the canoe so she steers herself.

How to determine the amount of leeway of steering error due the force of the wind on Hokule`a's sails? Watch the angle that the canoe's wake makes with her hulls.

How far away can you see landfall? It depends on the height of the island and, of course, the visibility. (A high island like the Big Island of Hawai'i--13,789 ft. high--can be seen from over 100 miles away; an atoll, on which the highest points are the top of coconut trees, can be seen from 8-10 miles away.)

Tikehau atoll

How can vog be helpful in finding the Big Island? If you see it, you are downwind of the island.

What is the overall current effect in the doldrums? None, because the currents are too variable to predict.

Nainoa's probing questions and his presentation of various scenarios are often accompanied by stories--a sharing of mistakes he has made with the obvious intent of indicating that navigation is, after all, a process of learning in which there is much trial and many errors. Take the case of sighting the Big Island at the end of the 1995 voyage, for example: "We were making our approach at night," Nainoa says, "and I was pretty confident that we were getting close but all I could see ahead were layers of light pink shading to purple then black. We couldn't see the island because of all the vog. Snake saw something glowing ahead. A fishing boat? We couldn't tell. It was a moment of panic. All of a sudden Snake said, "Hey, I think it's the volcano." It will be like that, you go through moments of panic and even hallucination combined with moments of intense insight."

The training sessions between navigator and students usually last for an hour or two after which the navigators either study together or by themselves to memorize the stars or various "formulas" for determining leeway, or current set, or go over their mental maps of the course to Hawai`i.

"Don't forget that this should really be fun," Nainoa told them at the close to one meeting this week. "Don't lose your excitement and your instinctual sense of knowing by too much studying. You have each other--remember that. I look forward to seeing you huddling together trying to figure things out. And don't worry. I won't let you do anything foolish but I also promise you, that I will let you do this trip--as much as possible--on your own."

Feb. 6, 2000 / Dawn--A Squally First Day at Sea

The winds, having been on vacation from Tahitian waters for almost two month, returned--with fireworks.

Yesterday after an emotional farewell ceremony, Hokule'a raised anchor early in the afternoon and passed through the reef at 2 p.m.

Tereraura says goodbye to expedition doctor Ming-Lei

While we were still close to the island, the winds were gentle--5-10 knots. As we released the tow line and were raising our sails, a bolt of lighting struck through the clouds at a low peak over Tautira. A few seconds later we were all jolted by a sharp crash of thunder and some crew members reported feeling an eletrical charge in their hands while they were coiling the halyards.

As Tahiti begins to drop lower on the horizon, the wind accelerates and swells pucker the ocean, passing under the canoe. Hokule'a leans against her lee hull and plunges forward--her responses slowed by the heavy load she is carrying.

All around the darkening horizon, too far away to hear thunder, lighting illuminates tight knots of clouds--squalls moving from east to west in the trade wind flow.

Nainoa divides the crew in half--five hours on watch and five hours off, to allow the maximum number of people on watch--a standard procedure in squally weather. The crew has to close up the sails when a squall approaches to prevent wind damage to the rig or the canoe.

First day out on our way home to Hawaii. Hokule'a is being steered by Nainoa who is showing Ka'iulani and Shantell some of the nuances of steering in variable winds ranging from 10-20 knots.

Squalls assemble to the east and rush toward us. We take in sail and roll in the troughs of waves, opening our sails again when the squalls has passed. The night is moonless and dark, concealing approaching squalls. We have to listen for them, watch carefully when the horizon is momentarily illuminated by lightning.

In the afternoon and evening the wind increases to 20 knots from the E-SE gusting from 40-45 knots with occassional squalls. The crew is forced to take in sail and heave-to about ten times on the first day at sea. Here Tava and Bruce change out a light wind to a heavy wind jib.

A little before midnight, Nainoa orders all sails brailed up and the jib taken down. A few moments later, we are shaken by 40-50 knot gusts driving rain and horizontal strata of water across Hokule'a's deck. A few waves crash aboard. Hokule'a shakes them off.

One such squall hits in the evening watch, another in the morning. By sunset the crew has been forced to close sails at least a dozen time. "If we hadn't closed the sails in time when the big squalls came through, we would be in some difficulty," says Nainoa.

At dawn, Shantell and Ka'iulani meet with Nainoa to report on the navgation: 72 miles from Tahiti. 52 miles to Makatea. "We should see Makatea in about 8 hours. After that, perhaps Mataiva." Nainoa reponds: "We have to be careful about approaching Mataiva. We can't see it at night, so figure your sail plan accordingly."

It's been an uncomfortable first night at sea. But everyone on the crew is doing well, working together wonderfully. We are looking forward to better weather today as we sail toward Makatea, a raised atoll between Tahiti and Rangiroa.

Feb. 7, 2000; 2 days since departure

At 4 a.m. comes the order to get under way--we had stopped sailing for six hours last night to wait for enough light to see our way through the dangerous low atolls of the Tuamotus. And what a night! We watched Orion pursue the Pleiades almost directly over the mast, as the Southern Cross arced upright and the Scorpion rose from the sea.

"I think the islands are right there," Nainoa says to Shantell this morning, gesturing toward the horizon where a rosy haze of clouds rises thousands of feet into the sky. "The eastern swell is gone. Something is blocking it. It must be the Tuamotus --Rangiroa is 40 miles wide."

We are reaching the end of the first leg of the trip--from Tautira to the Tuamotus. It has allowed the three student navigators to test their skills. If they can find their way through the Tuamotus, they can begin the next leg north to the doldrum zone with more confidence.

Yesterday the wind settled down out of the east and blew steadily at 10-15 knots. The squalls have disappeared.

We hoped to see Makatea in the late afternoon on Sunday, but the winds forced us to the west, so we passed the island unseen below the horizon. Not being able to sight Makatea as a stepping stone makes the navigation less certain. "But it's a good lesson," Nainoa reminds the three student navigators. "You often can't steer an ideal course, so you have to make changes in your mind all the time."

At the sunset navigator's meeting last night, Nainoa posed three questions to his students: "How many miles from Tahiti were we at 6 p.m. today? What is our latitude? Where are the Tuamotus and what is your plan for approaching them?" Earlier Nainoa, Bruce, and Chad concluded we were 30 plus miles west of Makatea and on a course and heading to intersect Mataiva during the night. "There is no moon and a little salt in the air, so it'll be difficult to see Matativa, even though there are plenty of trees on it. We should probably heave to around 11 p.m. tonight and wait for six hours, then set sail and go through the Tuamotus during the day."

Shantell, Ka'iulani, and Kahualaulani, calculate that between sunrise to sunset, we sailed 124 miles toward Na Leo Ko'olau (NNE). Makatea lies 124 miles from Tautira in about the same direction, so the canoe should be at the same latitude--15 degrees 50 minutes S. The winds pushed the canoe off the reference course to the west--32 miles west, they calculate. "So we are about 50-55 miles from Mataiva," Shantell reports to Nainoa. "Good, your dead reckoning position and mine are about the same, but I think we are about 49 miles from Mataiva." They agree that we should sail 25 more miles and heave to, then wait till just before sunrise to sail through the Tuamotus.

During the evening the wind shifts, and we sail NE, Manu Ko'olau, so this morning we sight Tikehau rather than Mataiva, and keep sailing. Before noon the atoll sinks into the ocean behind us and we trim our sails for the long voyage across an empty sea to Hawai'i.

Sighting Tikehau at dawn

Feb. 8, 2000; 3 days since departure / Calm Seas

A double rainbow frames Shantell, Kahualaulani, and Ka'iulani as they sit on the port navigator's platform considering Hokule`a's progress from sunset to sunrise, behind them Kamahele gleams, stark white sails and hull, against the towering cumulus clouds that ring the horizon. The clouds rise to about 10,000 feet and bend away with the impulse of a eastward moving upper air stream to form a swirling parasol above the escort boat.

"How did we do?" Nainoa asked Shantell at the morning navigators' meeting.

"We went an average of 5 knots for the 12 hours, heading haka."

In response to this report from his navigator Nainoa simply smiles and nods his head.

A slight adjustment was made yesterday when we departed Tikehau. The reference course, the imaginary geographic line along which the east-west position is plotted, was altered to begin at Tikehau --25 miles to the west of its former beginning point at Rangiroa. "This means that we have to keep those 25 miles in mind as we approach Hawai`i," Shantell explains, "and remember that our cushion for sighting land has been reduced from 275 to 250 miles."

The cushion Shantell speaks about is the distance to the east from the Big Island to where Hokule`a's reference course intersects the latitude of Hawai`i--the point where the navigators will turn the canoe west to begin their search for the Hawaiian islands.

"We always approach the islands from the east because it is relatively easy to determine our latitude and because it's much easier to search with a northeast tradewinds behinds us then tacking into them," Nainoa explains.

So the end game strategy goes like this: Hokule`a sails northeast from Tahiti across parallels of latitudes from that of Tautira, 17 degrees 44 minutes south, to that of the center of the Hawaiian islands, 20 degrees 30 minutes north. Using the stars, it's relatively easy to judge latitude to within a degree or so--about 60 miles --so the navigators guide Hokule`a to a rendezvous with 20 degrees 30 minutes north latitude and then turn west to begin their search. But if their dead reckoning is in error and they are already west of Hawaii, they would be searching empty ocean. Next stop Japan. Hence "the cushion." By steering from Tahiti toward a point 275 miles to the east of Hawai`I, the navigators provide a large margin for error in their ability to reckon longitude (their position east and west of the islands) by dead reckoning.

Yesterday we encountered the remnants of an upper level disturbance that occasionally descended to the surface, bringing squalls--one of them long enough for the crew on watch to take fresh water baths.

Life-giving Water of Kane: Tava gathers a handful of precious fresh water from a passing squall

The mid-day sun was hot, forcing the crew to seek shelter in shade pools cast by Hokule`a's sails. The tradewinds are now clearly established and we are moving along at a steady 5 knots.

Snake napping in the shade

Yesterday evening was another beauty, the horizon smudged with low clouds illuminated by an occasional flicker of lightning and the sky dome clear except for wisps of fast moving clouds.

"It's so beautiful out here tonight," Bruce says to the crew on watch, "and it's really difficult for me to explain it to my friends back home. You've just got to experience it to believe it."

The moon is a tiny upturned sliver, in a phase the navigators call hoaka, the second day since it was new and the sky was absent its sheen. With the moon almost aft our port beam, we steer northward toward Capella's pointers. The Milky Way is a glowing ribbon overhead which is matched by phosphorescent sparkles in our wake stirring up hundreds of darting squid. We are on a beam reach and a steady easterly wind and under these conditions Hokule`a will wander when asked to steer herself, so the giant center steering sweep is constantly manned. Kau`i relieves Tava on the sweep and aligns Hokule`a with the setting moon on our port beam. The sweep is angled to port by a simple device--a rope tied from its terminal knob to the safety railing along the deck. Kau`i partially sits on the sweep and partially leans against it applying weight to lift the blade from the water. Standing up she allows it to lower into our wake and steer us off the wind. Her motion becomes a kind of graceful dance. In choppy seas, the paddle undulates harshly--kicking back against the body of the steersperson; in relatively calm seas, its motion is gentle.

Wednesday, February 09, 2000--Light Winds

Yesterday (Tuesday, Feb. 8) we woke up to what seemed to be solid East winds accompanied by typical tradewind cumulus and we sailed well, working North for half a day.

Sunrise, Feb. 8

"In the afternoon we saw a large towering cumulus to the North," says Nainoa, "which indicated a probable breakdown in the trades."

Later in the afternoon squalls started to come through with a lot of rain but little wind. We had three squalls before sunset. After each of them there would be either no wind or a little wind but from the North so we would move for a time and then stall in our tracks, a pattern that Nainoa calls "jump sailing."

The pattern continued into the evening and morning of today, Wednesday--and at about 11 a.m. we remained virtually stalled in very light winds.

Shortly after sunrise a crew meeting was held aboard the canoe. Shantell presented today's navigation report: "We were at 10 degrees, 51 minutes S at sunrise," she says, "at about 10.5 miles W of our course line which is pretty much right on it. Everyone is doing a really good job of steering and in spite of the setbacks from the squalls we are doing very well."

At noon, Nainoa orders the largest sail possible bent on for the mizzen to take advantage of what little wind there is and we fix awnings over our decks to protect us from the blasting heat of this almost windless day.

Kona and Kau'i help put on a bigger sail for light wind conditions.

Thursday, February 10, 2000--Slow Going

Ua hala ka `ino, ua kau ka malie ("The storm has passed, calmness is here.")

It may begin with a rustling of the wind and then a fluky quality to it. The wind becomes restless--haunting. Then it begins to pulse. At night there might be a thickening in the darkness, a blotting of stars, then a dark line and, beneath it, a froth of white. The squall, approaching, seems to fan out--send out scouts first, then deploy its main body in a flanking maneuver, or it may rush ahead as if to harmlessly cross our bow then stop and lurk allowing us to sail up to it. Now the squall moves toward us, gathering mass, swelling, rising higher, pumping itself up and becoming something altogether more sinister than a mere thickening of the night, a thing, what to call it? A monstrous dark blob out there with malevolent intent.

Rain may proceed the wind which finally arrives accompanied at first by a deep whooshing sound--still distant--and then a moaning and the thumping of rain on Hokule`a's decks and the higher pitch of the rain as it strikes our canvas half-tents.

Way before all that has happened Nainoa will have climbed onto the Navigator's platform or ascended to the safety rail, standing with one hand on the rigging, examining the squall's intent. After a time, depending on the signs he detects, he will give the order to stand by the sails. The crew will disperse to their stations--three forward to take in the jib, four to the mizzen, which is the largest sail and so the one taken in first. One crewmember is at the sheet to loosen it; another at the clew to carry the sail forward as a third hauls down on the railing lines to pull the sail tight against the mast. The sheet is always paid out slowly to keep the clew from flapping in the wind and striking one of the crew.

We have experienced a range of squalls on our voyage--from the violent one on the first day with blasting winds accompanied by rapid bursts of lightning all around the horizon to Tuesday's downpour in almost still air. In the first squall the rain crossed the deck horizontally, in the second it was almost vertical.

"You have to watch the squalls carefully," Nainoa says, "if you see one coming to starboard, for example, you want to sail up to the last minute to let it go astern if possible because if it crosses in front of you it blocks your passage. A squall can create a kind of vacuum behind it in which there may be no wind for hours at a time. But, on the other hand, you don't want to wait too long because then the squall will hit you and it can do damage to our rig or endanger the crew. The first principle aboard this canoe is safety."

So far this voyage has been an interesting lesson in weather for everyone on board. We have experienced the gambit, from constant squalls (ten in a single day) to torrid days in which the sails hang limp and useless and the sun--in this windless world--is hot enough to be almost dangerous. It is as if we have sailed into some misplaced doldrums zone or into the aptly named "Horse Latitudes" at 40 degrees N or S where a constant high pressure area creates listless winds and the horses--carried aboard the ships of, for example, the Spanish Conquistadors--began to die of thirst.

From his office at the University of Hawai`i Bernie Kilonsky has a unique view of our situation--from space, using sophisticated computer imaging and models. He tells us what he sees via single side band radio transmission every day. Today, accompanied by wheezing static, he says: "I see an upper cloud layer thick to the S of you all the way to 20 degrees S--solid--but there are no organized storms in it. It's lucky that you left when you did, the convergence zone is settled solidly over Tahiti right now. If you were there it would be a long time before you could leave."

Bernie's computer model shows that we should be experiencing winds a little S of E at about 10 knots, but Nainoa reports to him that at the moment there is virtually no wind here. This situation appears to be a meteorological anomaly which neither Bernie or Nainoa can explain.

All decisions are made aboard the canoe, of course, but the ability to consult with Bernie provides an important measure of safety. Bernie consults daily with his colleague Tom Schroeder at University of Hawai`i's School of Ocean, Earth, Science and Technology as well as with meteorologists at the National Weather Service--organizations that have been providing what Nainoa calls a Weather Safety Net for the last 20 years.

"In general," Nainoa explains, "it is not rare to have light, easterly winds in this part of the South Pacific at this time of the year. It is normally better to sail in June from Tahiti to Hawai`i, but we are sailing now because this voyage was planned to take advantage of the weather in Rapa Nui. At this time of year the high pressure systems which cause the trades tend to be weaker and so the trades are lighter."

"The trough over Tahiti compounds our problem," Nainoa continues, "there is a lot of convection in it--rising moist air--which tends to pull the weak trade winds down into it, sucking the wind south toward it and shifting the winds that normally blow from the E to blow from the NE--and that's where we want to go."

The local pattern so far is for the rising air caused by the heat of the day to diminish the trades--stalling us. At night as the Earth cools, the convection dies down allowing the weak trades to reassert themselves. So, under the stars, Hokule`a makes her way slowly N while under the sun she and her crew endure--wait patiently--for the cool of the night.

February 11, 2000; 6 days out of Tahiti, forecasting weather by observing the clouds and sea state.

View from Hokule`a's beam--towering cumulus clouds:

Nainoa Thompson: "A Navigator always looks for signs of weather at sunset and sunrise," Nainoa says. "Generally, at sunrise and sunset you try to predict the weather for the next 12 hours. Today I see strong evidence in the clouds of a change in the weather from what we have experienced in the last 2 to 3 days. Looking to the east--off the beam of the canoe (this is picture 1) I see various complicated towering high cloud masses, which are the remnants of the squalls that we went through last night. Yesterday and the day before I looked out and saw actual squalls there--today there are no squalls evident. You can't really predict the weather, as Mau taught me, from a single snapshot like this. You have to observe changes over time. In this case, I see a change from seeing squalls off the starboard yesterday to this view today where there are no active squalls. The wind definitely feels stronger today and I can see wind wavelets on the surface of the ocean. The wind is also coming from the normal direction of the SE trades, so I can presume that the trades are reasserting themselves."

View towards the bow of the canoe from roughly dead ahead to 45 degrees off the bow:

"I see a lot of low level cumulus clouds ahead of us in the direction we are moving. There are no indications of any squalls in those clouds so I think I can predict we are approaching an area of clean flowing wind--trades from the SE--which will be steady. That is quite different than the variable winds we have been experiencing. So, for the next 12 hours, I believe that the wind will remain steady from the SE at a fairly constant speed, maybe 10 knots, so we will be able to sail N today."

"Every time I attempt to predict the weather or sail on this canoe I am constantly reminded of how smart our ancestors were. My understanding of nature is feeble compared to theirs. We can have today only a glimpse into their world--into the strength and courage that made them the greatest navigators and explorers on earth. We sail in comfort with foul weather gear to protect us on a canoe partly made of modern materials, with all kinds of safety devices on board. They had none of that. They were attuned intimately to nature in a way that we cannot be. At best, our voyages are just beginning to give us a glimpse into their world."

February 11, 2000--Moving Again; 6 days since departure

After breakfast every day, as the sun rises off the starboard beam, Nainoa calls a crew meeting. We generally assemble slowly--finishing chores already begun, on this day, for example, Pomai puts away galley utensils as Tava finishes washing dishes and buckets laid out on deck. Nainoa patiently allows the natural morning rhythms to complete themselves so that we are all ready to listen and exchanges ideas with each other.

Morning watch

Shantell Ching presents the Navigation report: "Our estimated position at sunrise is 10 degrees 11 minutes S. We had a good sailing day from sunrise, February 10th to sunrise, February 11th--76 miles N. We made up some easting and are now 16 miles W of our course line. We still have 2200 miles to go. We will try to hold Na Leo/Na Lani--2 _ houses E of N. Last night we got a fix on Kochab giving us a position of 10 degrees 30 minutes S. Our dead reckoning position is 10 degrees 11 minutes S, so the two are in pretty close agreement. We are doing great."

The calm days we have experienced in the last few days have actually been somewhat of a blessing--except for the heat, which is largely diffused by the twin shades over our decks.

Joey Mallot setting up a tarp for shade.

We've been able to take time to get to know each other better--to talk story, sing songs--at least some of us--and even try our hands at cooking a special meal.

Pomai and Kahua – Kanikapila

Last night Mike cooked fish (not fresh, unfortunately but a gift from Kamahele's freezer chest) taro, rice, fruits and a mix of spices, which he will not reveal. We wash clothes--Hokule`a's rigging is festooned with T-shirts, pareos, whatever. We read. We talk to our families via single side band phone patches and we talk to various school classes by satellite phone. We fish--but at this speed there is little chance of catching anything--and we plot ways to scoop up the schools of squid we have encountered almost every night. We take photographs and write in our journals. And that's just our recreational activities--activities that we actually have no time for when the wind is blasting.

When we are sailing hard there's much more effort extended in the basic chores of carefully steering the canoe, navigating, pumping the bilges, trimming sails and taking in and letting out the sails in squalls and all the other normal tasks associated with crossing 2400 miles of open ocean to find land.

Are we bored by the constant empty horizon, the repetitive path, and the--as it sometimes seems--slow moving passage of time? Hardly. There is always something to do, and we are always doing it with good friends.

All day yesterday was basically windless. We made perhaps a knot an hour maximum through the water. Sunset brought cooler air and a slight breeze allowing us to sail towards the N at about 4 knots. Today with the wind increasing we are steering Haka Ko`olau--one house E of N at about 5 knots.

Feb. 12

Sailing at sunrise

Tava and Shantell steering

Feb. 13, 2000 Sunrise

Dawn reveals a dark slate gray ocean, confused swells, white caps and a complex sky-veined and roped with clouds of all descriptions.

Nainoa goes over navigation with his students Kahua, Shantell, and Ka'iu, Sunday Morning, February 13. After a hard night of dodging many squalls, the navigators discuss their position. Because the night sky was almost totally clouded over,they had no opportunity to observe the stars, so they must estimate where they are by dead reckoning--averaging various headings, speeds, and deviations from their course.

It's as if mother nature had dug deep into her laundry bin to wash and hang out to dry every variety of cloud she owns. The canoe sails Naleo/Haka Ko'olau (one & two houses east of north) at 5 knots in a 10 to 15 knot wind from La Ko'olau (one house north of east). This morning the navigators estimate we are 40 miles to the west of our reference course at 7 degrees 16 minutes south lattitude.

We continue to deviate west of our ideal course due to the winds which are blowing from the north of east , forcing us to steer off to the west. "At some point we know we will have to make back the distance we have lost" says Shantell Ching, " but we want to continue moving north as efficiently as possible and to do that we are willing to deviate a little from our course line". During the day yesterday we went 43 miles and during the evening, in spite of many harassing squalls, we made good 37 additional miles toward Hawai'i.

Sunset

The dense clouds that have been following us now receeded far astern behind the gently swaying running lights of Kama Hele. Overhead, the sky dome is clear where the half moon now presents itself above our masts at sunset. The wind is cool. The crew don t-shirts and jackets as they go on watch. Tava, leaning against the aft safety rail says, "... going to be a nice night."

At 6 p.m., our navigators conclude we are at 6 22' S latitude and 58 miles west of our course line. Having sailed 54 miles since sunrise, we are now about 1880 miles from Hawai'i. Among the celestial clues we use to steer our course are: Mars, setting in Komohana (west); Jupiter and Saturn setting in La Ho'olua (1 house north of west); and Venus rising in 'Aina Malanai (2 houses south of east).

Tonight the navigators will pay particular attention to observing two pairs of stars: Murzim (a star near Sirius or A'a) and Alhena (in Gemini); and Saiph and Betelgeuse in Orion. During his painstaking observations of the stars in the Bishop Museum Planetarium, Nainoa discovered a variety of star pairs that appear to set simultaneously when the observer is at a very specific latitude. He calls this phenomenon "synchronous setting." Mirzim and Alhena, our first pair - and Saiph and Betelgeuse, the other pair both set simultaneously at only 6 S.

"We will be looking carefully at both star pairs tonight," Shantell says, "because we think we are about 6 S and so if they do set simultaneously, it will help confirm our dead reckoning position." In fact, the navigators have been mentally plotting their position through dead reckoning ever since departing Tikehau without a solid celestial observation as a reality check.

"Ideally, you only navigate by dead reckoning for about 360 miles when making a passage from Tahiti to Hawai'i," says Nainoa, "but because we have had so much bad weather we've been dead reckoning for about 750 miles and that's not comfortable. So I'm looking forward to getting some good celestial clues by looking at the star pairs and also observing Kochab or Holopuni."

During the morning navigator's meeting shortly after sunrise on Valentine's Day, the navigators report our position as 5 27' S, 68 miles west of our reference course line.

"We observed the two star pairs setting at the same time last night," Shantell says, "so we are pretty confident of our latitude. We are also pleased that our latitude estimates by dead reckoning are very close to what the stars indicate which give us additional confidence about our position."