Rapa Nui: Geography, History and Religion

(from Peter H. Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, University of Chicago Press, 1938. pp. 228-236)

Go to the island of my dreams and seek for a

beautiful beach upon which the king may dwell.

--Legend of Hotu-Matua

Polynesian Settlement: Hotu Matua

King Hotu-Matua dwelt in the land of Marae-renga and he dreamed of an island with a beautiful beach that lay over the eastern horizon. He sent men on a canoe named Oraora-miro to locate a beach on his dream island. He followed in their wake in his great double canoe, ninety feet long and six feet deep. One hull bore the name Oteka and the other Qua. The king was accompanied by the master craftsman, Tu-koihu, in another canoe. After many days' sail, the two vessels sighted an island that Horu-matua knew to be the island of his dreams. As they approached the western end of the island, the two vessels separated, the king to survey the south coast and Tu-koihu the north. The king's ship sailed rapidly and paddles were plied to increase the speed. The king's ship rounded the eastern end of the island without having seen the beach for which he searched. On the north coast he saw the canoe of Tu-koihu paddling in to a beach that he recognized as the beach of his dream. It would never do for Tu-koihu to land before him, so he invoked his gods with the magic words, 'Ka hakamau te konekone' (Stay the paddling). The paddles of Tu-koihu's crew stayed motionless in the water, and the sea seethed as the king's paddlers raced for the shore. The double prow of the king's ship ran up on the sands of Anakena, and Hotu-matua stepped ashore onto a beautiful beach fit for a king to dwell upon. And thus Hotu-matua added his name to the roll of famous navigators by discovering the eastern outpost that forms the apex of the Polynesian triangle. (Another version of the story of Hotu-Matua)

Geography

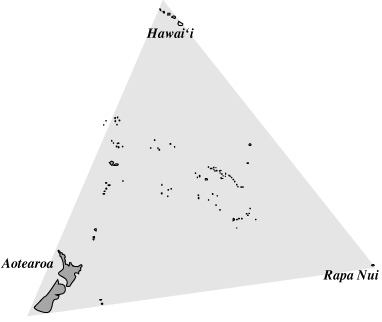

Easter Island is 1,500 miles from Mangareva, 1,100 miles from Pitcairn, and 2,030 miles from South America. [It’s and isolated island, at the southeastern corner of the Polynesian Triangle that includes Hawai‘i at the apex, and Aotearoa (New Zealand) at its southwestern corner.]

Its greatest length is thirteen miles and its area is sixty-seven square miles. It is a volcanic island with a dry, arid soil, no streams, and but slight rainfall. Of a number of extinct craters, Rano Aroi rises to a height of 6oo feet.

Southwest tip of Rapa Nui: the crater of Rano Kau; offshore, the pinnacle of Motu Kao Kao; from Georgia Lee, "The Rock Art of Easter Isalnd." Los Angeles: UCLA, 1992. Photo by W.D. Hyder, 1983.

European Contact

The island was sighted by the Dutch navigator, Roggeveen, on Easter Sunday, 1722. At that time it was occupied by a people of Polynesian stock speaking a Polynesian language. Later European voyagers, including Gonzalez and Cook, stopped at Easter Island and brought with them the diseases that decimated the populations of all Pacific Islands. In i 862, Peruvians carried off large numbers of the Easter Islanders into slavery. Of a remnant of 100 sent back after representation by the British and French Governments, 85 died of smallpox at sea and the 15 who were landed spread the disease throughout the island so that thousands died. A conservative estimate of the population before European contact is from 3000 to 4000. Fifteen years after the first depredations of the slavers, the population had dwindled to 111, of whom but 26 were females. The census taken in 1934 gave the total population at 456.

A French adventurer named Dutroux Bornier established himself on the island in 1870 and became so obnoxious that the Catholic missionary and his flock fled to Mangareva. More would have left but the schooner was crowded to the limit. Those who were forced to remain behind finally disposed of the foreign tyrant in the only suitable manner. The exiled inhabitants returned after the death of Bornier, but one wonders how many of the one hundred and eleven survivors were fitted to pass on the torch of knowledge to their descendants. No native population has been subjected to such a succession of atrocities and disintegrating influences as the people of Easter Island. It is no wonder that their native culture was so wrecked that the records obtained from the survivors are the poorest in all inhabited Polynesia. Unfortunately the early missionaries to Easter Island hadn't sufficient vision or interest to teach the native scholars to write down their history, legends, and customs.

The early European voyagers collected curios and wrote down what they saw and often what they did not see. Behrens, who accompanied Roggeveen, stated that the natives were so tall that the seamen could walk upright between their legs. He also saw pottery in a land where there was no clay. Paymaster Thomson of the U.S.S. Mohican, wrote of the material things he saw in 886, but even then it was too late to gather authentic information about ancient manners and customs. Mrs. Routledge made a survey in 1914 and her information about images, quarries, and platforms is valuable. Macmillan Brown visited later and his theory of a sunken archipelago has interested many. The Franco-Belgian Expedition visited the island in 1934 and later Dr. Alfred M~traux, a member of the expedition, worked up his field material at Bishop Museum. He and I had many discussions, and much of the information contained in this chapter was obtained from his manuscript which will be published by Bishop Museum.

Religion and Mythlogy

From the fragments we can reconstruct but little of the native mythology. Atea and Papa, the primary parents) have not been recorded. Tangaroa came to Easter Island in the form of a seal with a human face and voice. The seal was killed but, though baked for the necessary time in an earth oven, the seal refused to cook. Hence the people inferred that Tangaroa must have been a chief of power. Tangaroa also appears in the king's lineage with Rongo as his son. This scanty information is significant as an echo from central Polynesia.

Tane and Tu are absent from the pantheon but Tu-koihu is an early ancestor. He was a skilled artisan, which reminds us of the early functions of the god Tu in the Tahitian tale of creation. Hiro, the famous voyager of central Polynesia, occurs in an invocation for rain. The first line runs:

E te ua, matavai roa a Hiro e-

(O rain, long tear drops of Hiro-)

Ruanuku, a well-known god, occurs in a genealogy. Atua-metua is present in a creation chant. This name is intriguing for it resembles Atu-motua, one of the early gods of Mangareva. Though Atu (lord) and Atua (god) are different words, a change may have taken place in Easter Island. The qualifying words motua and metua are linguistic forms of the same word meaning father.

Atua-metua mated with Riri-tuna-rei and produced the nin. The word niu is the widely spread name for coconut but, as there were no coconuts on Easter Island, the name was applied locally to the fruit of the miro. The word tuna in the compound name of Riri-tuna-rei means eel, and it is evident that this fragment records a memory of the well-known myth of the origin of the coconut from the head of an eel.

The principal god was Makemake. The name does not occur elsewhere as the name of a powerful god, and Metraux thinks that it is a local name substitution for the important Polynesian god Tane. This theory is supported by the myth that Makemake created man on Easter Island in a way similar to that used by Tane and Tiki to form the first woman in other parts of Polynesia. Makemake procreated red flesh from a calabash of water. He mounded up some earth and from it he formed three males and one female. The process of mounding up earth is described in the local dialect as popo i te one, in which one is the general term for earth and popo is the local verb for heaping up, which in other dialects is aha.

The Easter Island creation chant, first recorded by Thomson in 1886 and checked over by Metraux with native informants, follows the pattern of such chants in other parts of Polynesia. Various couples are mated to produce plants, insects, birds, fish, and other objects. As in the Marquesas, Mangareva, and the Tuamotu, Tiki, here called Tiki-te-hatu (Tiki-the-lord), is mated with different wives to produce numerous offspring. Among Tiki's wives was Rurua who gave birth to Ririkatea, a king and father of Hotu-matua, the first king of Easter Island. By another wife named Hina-popia (Hina-the-heaped-up), Tiki produced a daughter, Hina-kauhara. In Hina-popoia we find a possible memory of the first woman, known elsewhere as Hina-ahu-one (Earth-formed-maid). Thus, from the wreck of local mythology, there remain a few definite indications that the mythology of Easter Island contained fundamental elements that originated in central Polynesia.

Makemake was responsible for the fertility of food plants, fowls, and the paper mulberry from which cloth was produced. When crops were planted, a skull representing Makemake was placed in the ground and an incantation was offered, commencing, 'Ka to ma Haua, ma Makemake' (Plant for Haua, for Makemake). Makemake was worshipped in the form of sea-birds, which may be interpreted as his incarnation. His material symbol, a man with a bird's head, was carved on the rocks at the Orongo village. Wooden images representing him were carried at the feasts. Human sacrifices were made in his honour and the material part was consumed by the priests. These various items conform to a general Polynesian pattern, but the bird-headed man is an expression of art influenced by local developments.

Of the organized forms of religious ritual we know little. Priests presided over birth festivals, drove out disease demons, and regulated funeral ceremonies for which they composed dirges. The priests were termed ivi-atua (people of the god), which has an affinity with the Mangarevan term for priestly chants. Human sacrifices were termed ika (fish), a widespread Polynesian term which probably had its origin in an early period when religious offerings consisted principally of fish. Sorcerers and priestesses who claimed to be the medium of deceased relatives who had something to communicate functioned much as in the religious systems of other Polynesian islands.

The spirits of the dead were called akuaku and were represented by the carved wooden images termed moai kavakava with protruding ribs and sunken abdomens. The spirits were stated to have introduced tattooing, turmeric dyes, and a variety of yam, which they must have brought from the land of the dead away to the westward. The Easter Islanders shared in the general Polynesian concept of a spirit land, not as a place of reward or punishment but simply as a land beyond the grave to which the undying souls of all men may return.

Traditional History

The traditional history is almost as poorly transmitted as the mythology. Hotu-matua took up his residence at Anakena and shortly after the landing his wife Vaikai-a-hiva gave birth to a male child. Tu-koihu cut the navel cord of the child and conducted the ritual whereby the royal halo (ata ariki) was produced around the child's head to indicate its royal birth. He was named Tu-maheke and through him descends the line of Easter Island kings. On the basis of fragments of royal genealogies, Metraux has estimated that Hotu-matua landed on the island in about I 150 A.D.

As in other parts of Polynesia, tribes developed with increase in population, taking the names of ancestors and living in definite districts of the island. The highest ranking chief, who also had priestly functions, belonged to the senior line descended from Hotu-matua. This tribe was named Miru and ranked above the other tribes, enjoying certain special privileges.

Inter-tribal wars were frequent and the tale of the war between Long-ears and Short-ears may indicate that there were two early groups of settlers; one group, which pierced their ears and wore such heavy ornaments that their ears were considerably elongated, coming from the Marquesas where heavy ear ornaments were worn, and the other group which did not pierce their ears coming from Mangareva. The Long-ears lived on the eastern end of the island and were credited with making the stone images which have long ears and the stone temple structures. The Short-ears lived on the western part of the island and had the more fertile lands. The Marquesans carved large stone images and built stone retaining walls, whereas the Mangarevans did not. Conflict arose because the Short-ears refused to carry stones to assist the Long-ears in erecting a temple. In the war which followed, the Long-ears were said to be almost exterminated. This may account for what appears to have been a sudden cessation of work in the image quarry and the commencement of knocking down the images from their platforms.

Birds and Bird Cult

The fowl, which was the only domestic animal known in Easter Island, may have come from the Marquesas where it was present but not from Mangareva where it was absent. Because it was the only domestic animal, the fowl received more attention and honour than in any other part of Polynesia. Fowls became the mark of wealth, and festivals were characterized by gifts and distributions of fowls. In order to protect them from thieves, fowl houses of piled stones were erected to house them at night. Stones were piled up against the entrance and the sound of stones being moved served as an alarm to the owner. Skulls with incised carvings, imbued with power by Makemake, were placed in the fowl house to promote the egg-laying capacity of the occupants.

It may seem a long call from the domestic fowl to the sooty tern, but both are birds and lay eggs. The sooty tern (manu tara) comes to breed in large numbers in July or August off the southwestern point formed by the crater of Rano-kao on three rocky islets, of which the only one accessible to swimmers is Motu-nui. What commenced as an ordinary food quest for eggs became an annual competition to obtain the first egg of the season. The warriors (matatoa) of the dominant tribe entered servants for the annual Derby, and members of defeated tribes were not allowed to take part in the competition. The selected servants swam over to Motu-nui and waited in caves for the migration of the birds. The warriors and their families assembled on the lip of Rano-kao that overlooked the course. Owing to the strong wind, they built houses of stone for shelter at the village named Orongo, the Place-of-listening. There they listened for the coming of the birds and waited for the call of the successful servant who found the first egg. While waiting they amused themselves with singing and feasting and carved on the adjacent rock figures with birds' heads and human bodies, the symbol of Makemake, god of fowls and sea-birds. In time, rules and ritual were developed about this annual competition which became the most important social event on the island. The successful servant leaped onto a rocky promontory and shouted across the water to his master, 'Shave your head. The egg is yours.'

A sentry on watch in a cave below Orongo, termed the Bird-listener (Hakaronga-manu), heard the call and relayed the message up to the waiting masters. The successful master was termed the Bird-man (Tangata-manu). On reception of the egg, the people escorted him to Mataveri, where a feast was held in his honour. After that he went into seclusion for a year in a house at Rano-raraku. The details of his functions and privileges are not known, but certain it is that he was held in high honour and provided with food by the people until the next annual Derby took place. The list of Bird-men was memorized and transmitted like a line of kings. The bird cult is not known elsewhere in Polynesia and is clearly a local development arising out of peculiar local conditions. The importance of the fowl as the sole domesticated animal, the annual migration of the sooty tern to a near-by islet to breed, the village of Orongo with its carved rocks overlooking the course, and the development of the bird cult are all in a natural sequence that could have occurred nowhere else but on Easter Island.

Lack of Wood

Easter Island has little fertile soil and no forests with large trees to provide adequate raw material for houses and canoes.

Consequently the framework of houses was made of slender arched poles, and houses were narrow, low, and long. In order not to waste valuable inches, the poles were not stuck in the ground but rested in holes carved out of stone blocks. These pitted curbstones, like the elaborate bird cult, are unique on Easter Island, evolved locally due to lack of timber.

Canoes at Contact

The canoes were poor and flimsy, but ten to twelve feet long and formed of many small bits of wood sewn together. Even the paddles were made of two pieces: a short, narrow blade with a separate handle lashed to it. The two-piece paddle is unique for Polynesia, but again the form of the canoe and paddle was a local adjustment forced upon the people by the lack of material. Successive European voyagers saw fewer and fewer canoes on Easter Island, not because of degradation in the population, but because of constant decrease in the wood supply. The people swam out to ships sometimes with a supporting float formed of a conical bundle of bulrushes. Wood was as precious as gold in Europe or jade in New Zealand. The minimum quantity was used for necessities, and the surplus constituted wealth in the form of wooden breast ornaments, dance implements, and carved tablets.

Arts of Easter Island

Macmillan Brown in his work on 'Peoples and Problems of the Pacific' condemned the arts and crafts of Easter Island as being the most primitive in Polynesia. This is manifestly inaccurate and unfair. Apparently he did not take into consideration the vast importance of environment and its influence on all forms of material culture. The feather headdresses of Easter Island compare favourably with those of the Marquesas and Tahiti and are vastly superior to any similar work in Samoa and Tonga. The bark cloth is remarkable, for the shortcomings of the original material are overcome by quilting with threads by means of a bone needle. The carving of wooden ornaments, stone images, and the development of decorative techniques, such as the representation of eyes by means of a shell ring with a black obsidian pupil, are among the most remarkable in all Polynesia. Brown has condemned the Easter Islanders for not making greater use of bone, turtle shell, and obsidian to inlay their wood carvings, but neither did the other great branches of the Polynesians. The most unfair criticism is levelled at the implements, which are classed as childish. The adze or toki is stated to be a blunt round stone rarely ground to an edge or rubbed smooth. It is evident that the critic was referring to the hand implements that were used to shape the stone images in the rough. He totally disregarded the adzes that were used in woodwork, which are better made than those of Mangareva and Samoa. Some of them are well shaped but with a blunt edge and they were probably used as hand adzes to finish off the stone images after they had been taken from the quarry.

Moai: Stone Statues

The stone statues of Easter Island have intrigued the imaginations of many, and a mystery has grown up around them. Some have believed them to be the work of some extinct race from a vanished continent. Yet the simple truth lies at the feet of the statues. Large stone images were made in the Marquesas and Raivavae and smaller ones in the Society Islands, Hawai'i, and New Zealand. The Easter Islanders carried the memory of stone carving from the Marquesas to their new home, where they developed a local pattern adapted to the soft, easily worked volcanic tuff found in the extinct crater of Rano-raraku.

The images have high faces, long bodies, and arms but no legs. They are really busts. Some were placed on stone platforms near the coast and others were dotted about the landscape. Those on the platforms had expanded bases to enable them to retain an erect position. The others had peg-shaped bases for insertion in the ground.

The process of carving these statues may be deduced by an examination of the unfinished forms still lying in the quarry workshop in the crater of Rano-raraku. The figures were roughly shaped with the face uppermost. Then the sides were undercut and rounded, leaving a narrow ridge along the back to hold the statue in position. Finally this flange was cut and the detached figure was hauled to its site of erection. There the ridge along the back was trimmed off. Near some figures in the quarry lie rough stone tools shaped from hard nodules in the tuff, apparently left by workmen when the image factory went out of business.

Macmillan Brown has proposed that the statues were made in the image of their mysterious creators from a now submerged land-strong, imperious men with shapely chins and scornful, pouting lips. At this statement a physical anthropologist stands aghast; if the Easter Island images resemble their sculptors, then the Marquesan images with round, owlish eyes, noses with expanded wings, mouths stretching the full width of the face, must represent their makers. What a nightmare the image makers of Polynesia would present if they were recalled from the spirit land and made to conform to the anatomy of their creations I

The difficulty of transporting the images has been adduced as an argument in favour of a large population coming from elsewhere with ropes and mechanical appliances to move the images. The present Easter Islanders were considered too weak and lazy to have had ancestors who could do hard work. The Tongans, Hawaiians, Tahitians, and Marquesans moved large masses of stone and set them in place with ropes, wooden levers, skids, and props, and built up inclined planes of earth and rock to accomplish their tasks. Brown's assumption that the images could be moved only by thousands of slaves coming from an imaginary archipelago is based chiefly on one image fifty feet high which was never removed from the quarry. The average height of the images is ten to fifteen feet and their weight between four and five tons. I doubt if the images were heavier than the logs that the Maoris dragged from the forest for their war canoes or for the one-piece ridgepoles of their large meeting houses. United man-power can accomplish much, especially when such public works were made the occasion for a festival, with feasting according to Polynesian custom.

Originally the stone images may have represented gods and deified ancestors but in the course of time they became more truly an expression of art. The images with pegged bases were never intended to be placed on the stone platforms of the temples but were to be erected in the ground as secular objects to ornament the landscape and mark the boundaries of districts and highways. Because the images remaining in the quarry all have pegged bases, it would appear that the orders for the platforms had been filled and that the people had embarked on a scheme of highway decoration when war or contact with white foreigners caused operations to cease for ever.

The stone temples of Easter Island were built near the shore line as in other Polynesian islands, and the theory that they were so placed to exercise a magical influence in preventing the encroachment of the sea is untenable. A stone retaining wall was built near the coast, and the inland side was filled in with rock to form a sloping surface which was defined on the inland side by a low curb, sometimes stepped. The middle section of the retaining wall was higher than its wings and thus provided a raised platform upon which a number of images facing inland were placed on flat stone pedestals. Beyond the low inland curb a roughly paved area represented the paved court of the maraes of other groups. The entire enclosure was called ahu, a term used in central Polynesia to designate the raised platform at the end of the marae court. Recesses or vaults were provided in the mass of stone as tombs for the dead, a usage not confined to Easter Island. Owing to the loss of religious association and ritual, the ahu have come to be regarded as cemeteries, which was a secondary function of the older structures.

Wooden Tablets and Rongorongo Script

The wooden tablets with rows of incised characters have been the greatest problem in solving the so-called mystery of Easter Island. Legend states that King Hotu-matua brought sixty-seven tablets with him from the island of Marae-renga. If this is so, the use of such tablets must have been well established in that land. Cultural and mythical evidence seems to point to the Marquesas and possibly to Mangareva as the lands of origin of the Easter Island people, yet neither of these islands, nor indeed any Polynesian island, retains a memory of such tablets. Did they come from some land beyond Polynesia or were they evolved in Easter Island itself?

Students of Polynesia were startled to learn that characters similar to those on the tablets had been found on seals excavated at Mohenjo Daro in the Indus valley in India. A European investigator arranged in parallel columns selected characters from the seals and from Easter Island tablets that were similar or even identical. However, a careful analysis by Metraux showed that certain motifs had been rendered more similar by inaccurate drawing. In any event, the identity of characters would tend to raise suspicion rather than to confirm a common origin. It has been demonstrated time and again that figures do not remain identical during prolonged transmission. Easter Island lies over I 3,000 miles from Mohenjo Daro, whose civilization is dated at 2000 B.C. How could these characters survive the dangers of flood and field during a migration of over i 3,000 miles of space and through 3000 years in time to arrive unchanged in lonely Easter Island and leave no trace between, not even in Marae-ranga whence Hotu-matuawas supposedto have broughtthe tablets?

We cannot suppose that the tablets themselves were brought from Mohenjo Daro, for the Easter Island tablets have a boustrophedon arrangement, that is, alternate rows are upside down. Such an arrangement has not been discovered in Mohenjo Daro. Also, the Easter Island tablets are made of local or drift wood, the largest one being made from the blade of an ash oar which must have drifted to Easter Island in the early eighteenth century. Hence there is little doubt that the tablets were carved in Easter Island itself long after the time of Hotu-matua, but were attributed to him to give them the increased antiquity that all Polynesians revere.

The tablets of local wood are flat, oblong pieces with rounded edges and are neatly cut in shallow parallel grooves with distinct edges bounding them. Commencing with the lowest groove on one surface, the carver worked from left to right; when he reached the right end, he turned the tablet upside down in order to carve the second row from left to right. Both surfaces of the tablet and even the side edges are completely covered with rows of figures. As it is difficult to understand how any written chants or records could so correspond to the size of the tablet as to exactly fill it in every instance, it is probable that the characters are purely pictorial and are not a form of written language.

The tablets were called kouhau, which, in the dialects of Easter Island, Mangareva, and Marquesas, means a rod (kou) of hibiscus wood (hau). In the Marquesas, bundles of hibiscus rods were placed vertically at the corners of religious platforms as part of the temple regalia. In Mangareva, the term kouhau was applied to hibiscus rods that were used to beat time for certain ritual songs and dances. From the use of the term kouAau in Easter Island, it would seem that the art motifs were carved originally on a staff of hibiscus and, if done along the length of the staff, it may account for the technique assuming the form of long rows. Owing perhaps to the need of lengths of wood for other purposes, the carving was transferred from staves to shorter pieces of wood in the form of tablets which retained the name kouhau.

The tablets were used by scholars termed rongorongo, who sang the old chants at various festivals. In Mangareva, the learned men who chanted at festivals and during religious ritual were also termed rongorongo. In the Marquesas, the inspirational priests who chanted were termed o'ono, the dialectical form of orongo. When the Easter Island rongo-rongo chanted, they held a tablet in their hands and when, in later times, a tablet was shown to an Easter Islander, he took it in his hands and commenced chanting. The connection between chant and tablet seemed so obvious that European observers never doubted but that the carved figures on the tablets definitely represented the words of the chants and were thus a form of writing. When Bishop Tepano Jaussen heard an Easter Islander chant to one of the tablets, he wrote down the words that were chanted to the various characters on the tablet. An analysis of the written native text proved to be a brief naming of the individual characters, some obvious and many doubtful. Though delivered as a chant, the whole composition had no connected meaning and was obviously made up on the spot to satisfy a white man's desire for a chanted ritual of the characters on the tablet. Any Polynesian can improvise a chant. I have improvised chants to lengthen out a recital for a European audience that did not understand the language. Neither the bishop's informant nor I had any intention of deceiving, but we were both influenced by the desire to please.

Judged from a Polynesian background, I would suggest that the rongorongo chanters originally carved figures representing Makemake and art motifs connected with the bird cult on staves termed kouhau, which they held in their hands while they exercised their duties. Later the motifs were inscribed on wooden tablets, and the natural desire not to waste any space led to the tablets being completely covered. Again to make the most of the material, the tablet was adzed or chiselled in contiguous grooves to form ordered rows for the carving. The normal technique of working from left to right and the desire to commence the first figure in a new line close to the last figure in the previous line led to the boustrophedon arrangement of successive rows. The artistic tendency to avoid monotonous repetition of a few figures led to variations of the main motifs derived from the bird cult and the addition of new figures that were regarded purely as art motifs. The tablets became works of art and, as valuable possessions, they were given individual proper names in the same manner as jade ornaments in New Zealand. The Easter Islanders, like other Polynesians, learned their chants and lineages by heart. They held the tablets in their hands as symbols replacing the orator's staff.

The Easter Islanders have been badly treated by popular writers. Erroneous assertions have been piled up one after another to make their arts and crafts appear so poor and futile that the task of making the stone images and of transporting them would appear to be beyond the capacity of the ancestors of the present people. The mystery has been deepened by regarding the art tablets as a form of script and so foreign to Polynesian culture. Because western people are now incapable of making stone images without steel tools and of transporting them without modern machinery, the very culture of the Easter Islanders has been attributed to a mythical people who never existed. Yet the fact remains that the descendants of Hotu-matua used the raw material of their little island to an extent that the western mind seems to find difficulty in realizing. The resurrection of an extinct civilization from a sunken continent to do what the Easter Islanders accomplished unaided is surely the greatest compliment ever paid to an efficient stone-age people.