Nainoa Thompson

The following biography/autobiography is framed by “The Ocean Is My Classroom,” written by Gisela E. Speidel, Editor of The Kamehameha Journal of Education, and Kristina Inn, Associate Editor. “The Ocean Is My Classroom” was published in The Kamehameha Journal of Education (Fall 1994), Vol. 5, 11-23. Inserted into the frame are narratives taken from two speeches by Nainoa Thompson: the first speech was for a Polynesian Union conference sponsored by the Queen Emma Foundation in 1997; the second was to Hui Lama, at Kamehameha Schools, in April, 1998. Additional information came from interviews by Sam Low, during the Voyage to Rapanui, Mangareva to Rapanui, 1999 and other sources.

Introduction

Nainoa Thompson, navigator for the Polynesian Voyaging Society, has inspired and led a revival of traditional voyaging arts in Hawai'i and Polynesia-arts which have been lost for centuries due to the cessation of such voyaging and the colonization and Westernization of the Polynesian archipelagos.

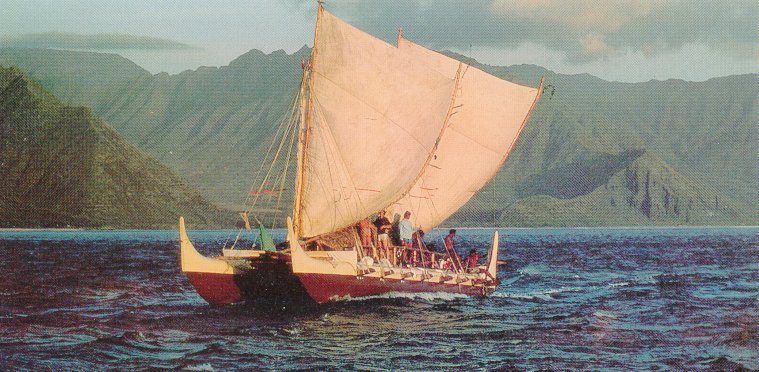

2000 Voyage Home. Photo by Sam Low

In 1980, Thompson became the first Hawaiian and the first Polynesian to practice the art of wayfinding on long distance ocean voyages since voyaging ended in Polynesia around the 14th century. Thompson has developed a system of wayfinding, or non-instrument navigation, synthesizing traditional principles of ancient Pacific navigation and modern scientific knowledge. This system of wayfinding is being taught in schools throughout Hawai'i the Pacific. In addition to being a navigator, Thompson is a leader with a vision, and a charismatic, spell-binding storyteller. The following accounts of the revival of voyaging and navigation in moddern times, the history of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, and the Society's long-range vision and mission for rethinking the future of Hawai'i, is presented, as much as possible in Thompson's own words-from his interviews, talks and writings.

Childhood and Schooling

Nainoa grew up on his grandfather's dairy and chicken farm in Niu Valley-when the valley was still all country. It was Yoshio Kawano, the milkman, who introduced the ocean to Nainoa. Dawn would often find Nainoa sitting on Yoshi's doorstep, waiting for Yoshi to take him fishing. Yoshi would bundle Nainoa into the old car, and off they'd go to fish in the streams or on the reefs. He came to be at home with the ocean, feeling the wind, the rain, the spray against his body. To the five-year-old Nainoa, the ocean was huge, wild, free, and open. The ocean and the wind were always changing; this was so different from the serenity of the mountains and the farm. Nainoa came to sense and feel the tune of the ocean world, develop-ing a personal relationship with the sea. These early experiences, Nainoa thinks, were an essential preparation for becoming a navigator: "We learn differently when we are young; our understanding is intuitive and unencumbered."

Nainoa learned from Yoshio; he learned from Dad, from Mom, from Grandma and Grandpa; he learned from those who loved him and showed him kindness. Nainoa thrived.

This all changed with school! How different learning was in school! Teachers were not close personal friends who cared for you, whom you trusted. One grade-school teacher made him stand the whole period in the back of the classroom with his face against the wall. More than 30 years later, Nainoa remembers sharply his mortification; what he doesn't remember is what he did to deserve that punishment.

Nainoa recalls, "My family didn't push competition. The idea of competition didn't make sense to me. Why should I compete with my friends, the guys I liked and played with? The idea of grades didn't make sense. What do grades have to do with learning. Learning should be something very special, very exciting. Rather than learning eagerly, I found that I was spending my energy avoiding bad grades. School should be relevant, exciting, and interesting. I used to ask, 'Why are we reading this book? Why are we reading about dead people in faraway lands?"'

Was it the teacher who had made him stand facing the wall who told his parents she worried that Nainoa was mentally slow? Or was it the tester who tested him for entry into Punahou School' at third grade? Nainoa hadn't answered any of her questions because, as he explained to his dad, "I didn't know who she was." Whatever the cause, Dad decided to have Nainoa's intelligence tested by a psychologist-a family friend, a friend whom Nainoa trusted. Result: Nainoa scored off the top of the intelligence scale. But, the psychologist sensed Nainoa's need for trusting and caring teachers and predicted trouble for Nainoa's learning under typical classroom conditions.

Nainoa now realizes this: "It was really important to me that I could trust a teacher and feel the teacher cared for me; Mrs. Hefty, she was great! She was my fifth-grade teacher. She was so understanding and sincere; she cared for me. Intuitively, she knew how to reach out to me. With her, I had no fear of failing; I could learn anything from her." Mrs. Hefty must have, indeed, been special. She lives on the mainland now, but Nainoa still corresponds with her, and whenever he comes back home from one of his long and dangerous voyages on Hokule'a, a letter is there from Mrs. Hefty to welcome him back and to congratulate him.

Upon graduating from Punahou School, Nainoa was unsure of where he was heading. For a while, he spent his time fishing and working in construction, driving dump trucks, ... and he started to paddle outrigger canoes at the Hui Nalu Canoe Club.

Nainoa's eyes light up as he recalls, "It was the first year I was paddling, and 1 happened to be at the right place at the right time. Across the canal from the club, Herb Kane was living. Just at that time, Herb, Tommy Holmes, and Ben Finney were designing Hokule'a. It was 1974, and the canoe hadn't been built yet. They had a smaller canoe then, and they'd ask us to paddle it out of the canal over the reef into the open ocean. That was great! I was at the club every day so I could paddle the canoe out.

"Then one day, Herb invited two of the paddling coaches and me over to his house. Herb's house was filled with paintings and pictures of canoes, nautical charts, star charts, and books everywhere! Interesting books! Over dinner Herb told us how they were going to build a canoe and sail it 2,500 miles without instruments-the old way. 'We're gonna follow the stars, and the canoe is gonna be called after that star" Herb said, pointing to the star Hokule'a. This voyage would help to show that the Polynesians came here by sailing and navigating their canoes-not just happening to drift here on ocean currents or driven by winds. The voyage would do something very important for the Hawai'ian people and for the rest of the world.

"In that moment, all the parts connected in me that had seemed unconnected in my life. I was 20! I was looking for something challenging and meaningful! I had a hard time finding that in the four walls of the school. Here it was- in the history, the heritage, the charts, the stars, the ocean, and the dream ... there was so much relevance in that dream. I wanted to follow Herb; I wanted to be part of that dream."

Did the dream, at that time, include becoming a wayfinder? "Oh, no! At that time, all I wanted was to be part of that dream to sail to Tahiti on the Hokule'a; all I wanted was to learn all I could about sailing.

"Herb told us what the requirements would be to sail to Tahiti. We would have to go through a training program in which we would learn all about the canoe and how to sail her, and there would be physical training and training in teamwork. They would select the best 30 from the several hundred who participated in training.

"When Hokule'a was completed in Spring 1975, I participated in the training and was assigned to the return crew! If I want to do something, I can be very disciplined. My dream was coming true!"

On scientific inquiry into Polynesian Pre-history (Polynesian Union speech):

About forty to fifty thousand years ago, when the earth was colder and much of the ocean that we know today was trapped in the polar caps, the sea level was lower by about a hundred meters, three hundred feet. Australia, Melanesia, Indonesia were connected to the Asian continent. The first explorers into the Pacific came by foot and they walked out of the South China Sea area and occupied the land mass in Australia. As our people went south, other people went to the north and crossed the Siberian Peninsula on foot and occupied North and South America.

By the time the earth got warmer, the polar caps melted, sea levels rose and the people in Melanesia became islanders. We believe that they were able to island hop across short distances. Maybe they didn't even need to sail. They could have done it in crude rafts; they could have paddled. The longest distance between two islands in Melanesia was only eighty-seven miles. The islands then settled in what we now call Western Polynesia-Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji. There they became somewhat "island-locked." To make this "jump" from Western Polynesia into what we call Eastern Polynesia took them a thousand years. They developed the canoe, navigational systems and the ability to sail long distances. Once they were able to make this crossing, the expansion of Polynesia was quick. Hawai'i to the north, Rapanui in the east, and Aotearoa in the southwest.

We are taught in our history books today that the inhabitants of the Polynesian triangle were a people of common language, of common ancestry, of great achievements in exploring the earth. Consider the fact that there was no other culture in their time that was ocean-going ... deep sea ocean-going. In my opinion, these explorers were the greatest explorers on the earth at the time. If you exclude the total land mass of Aotearoa, there is three hundred times more water than there is land ... ten million square miles of ocean. And that is what makes their achievements more amazing. This is geographically the largest "nation" on earth. It's bigger than Russia. There was adze found in the artifacts on the beaches of Australia that are Polynesian. And also, through the sweet potato, we know that there was contact to the Americas. And just in recent times through the new science of genetics, there is evidence showing that the Native Alaskans, Haida Indians, have Polynesian blood.

How did the Polynesians do it? How did they build canoes from limited resources on small islands? How did communities come together to combine resources, material, and manpower, to build and sail these voyaging canoes? How did they navigate? How did they guide themselves across ocean expanses of 2500 miles long? And how did they transport all the food resources necessary for societies to flourish on uninhabited islands?

Three individuals back in the mid-1960s got together as they were very disturbed by the fact that individuals like Thor Heyerdahl suggested that the Polynesians could not sail upwind, into the weather. They could not come from Asia -- from west to east --against the prevailing tradewinds. Their canoes were not very seaworthy. There were those like Andrew Sharp in New Zealand who said, that from an anthropological point of view, Polynesians came from an Asian origin, but they were not smart enough to navigate more than. one hundred miles in the open ocean. These three people – Ben Finney, Herb Kawainui Kane, and Tommy Holmes – got together and said, well, we want to debate that. And the only way we can debate it is to build a canoe and sail to Tahiti.

On the Building of Hokule'a, 1973-1975 (Polynesian Union speech):

Hokule'a was built out of scientific inquiry, not culture. She is sixty-two feet long and about nineteen feet wide. And she carries a full load of about 26,000 pounds.

She was launched from a beach on this island called Kualoa, a very sacred place, on March 8, 1975.

On the designing of Hokule‘a (Hui Lama speech):

We know very little the design of ancient canoes. Much has been lost in the last 200 years. This is an etching - by an artist named Webber on Captain Cook's second voyage - of canoes in Kealakekua Bay but they are not voyaging canoes. The main evidence that we have of what the voyaging canoes were like came from this island called Huahine, which is about 110 miles west of Tahiti. In this area called Maeva, they were building a hotel called the Bali Hai and when they were digging up the ground they found some canoe bailers and so they called Dr. Sinoto from the Bishop Museum and he went down and conducted an excavation. He thinks that six hundred to a thousand years ago there was a canoe under construction here and the work place was hit by a Tsunami which buried the canoe under mud and sand and preserved it by cutting off the oxygen that causes rot.

Dr. Sinoto at the excavation site on Huahine.

Here is an actual plank of the canoe and this is a coconut fiber aha still holding the planks together. And here there was a knot in the plank and what they did was to put wood in from behind and lashed the two pieces of wood together it make a sandwich. Dr. Sinoto guesses that this canoe was 72 feet long, ten feet longer than Hokule'a. In the earliest days of Hokule'a, when she was going through sea trials, the steering mechanism was like the kind we use on a six man canoe but the problem was that a six man canoe weighs 600 pounds and Hokule'a weighs - fully loaded - about 24000 pounds and guys who were trying to steer her were getting knocked out, ending up in the hospital, and it wasn't working and I was looking at that thing and saying, "oh, man, it is really going to be a long trip. And so some of the beach boys said, "we are not going to do it this way anymore. We have got to come up with a steering sweep. And so they designed a steering sweep that would work - from their experience at Waikiki - and it solved the steering problem. And the steering sweep that they pulled out of that swamp in Huahine - it was discovered after the beach boys figured out how to design a sweep for Hokule'a - and this sweep is very similar in design and only two feet shorter than the ones we use to steer Hokule'a.

On The First Voyage to Tahiti, 1976 (Hui Lama speech):

Hokule'a's first voyage in 1976 was from Honolua Bay, Maui, to Papeete, Tahiti-a distance of twenty-five hundred miles.

Back in the early seventies, before Hokule'a was even built, when they were putting the dream together, they said, "we need to get a Polynesian navigator" – someone who could sail to Tahiti in the way the ancient Hawai'ians had, a navigator who could find the way without modern instruments. There was no one in Hawai'i. The only navigator that was known to be left on earth was a man by the name of Tevake.

He came from a small island - not in Polynesia - but in a Polynesian outlier in Melanesia. A group from Hawai'i went down to his island to talk to him to see if he could navigate a canoe that wasn't even built. They explained the project and all Tevake said was, "we'll see." He gave no commitment. That is the old way. And the group went back to Hawai'i and six months after that trip the group received a letter from Tevake's daughter. Apparently Tevake had an old canoe house in which there was an old canoe that he never used. But one day he got up, said good-bye to his whole family, got on the canoe, went to sea and never came back. That's the way that Tevake was - the old way. He chose his life to be in the ocean and it was there that he chose his death.

So now there was a problem. We were facing cultural extinction. There was no navigator from our culture left. The Polynesian Voyaging Society eventually found a traditional navigator to guide Hokule'a, a very special man. Without him, we have to realize that our voyaging would never have taken place. His name is Mau Piailug and he is from a small island called Satawal in Micronesia. To provide for his people, Mau still sailed canoes for long distances across the Pacific, guided only by the stars and his knowledge of the ocean.

Mau was willing to come. He navigated Hokule’a on her first historic voyage in 1976 to Tahiti. Kawika Kapahulehua skippered the canoe. Never before had Mau been on such a far journey, never before had he been south of the equator where he could not see the north star, a key guide for his travels. Nevertheless, sensing his way over 2,500 miles, using clues from the ocean world and the heavens, cues often unnoticeable to the untrained eye, he found, after 30 days of sailing, the island of Mataiva, an atoll in the Tuamotu Island group! Thirty three days after she left Maui in 1976 Hokule’a entered Papeete Harbor. So it was possible after all for the Polynesians to have come from Tahiti with their double-hulled canoes to settle Hawai'i!

I was not on that crew. I was on the return trip. But I flew down to Tahiti and watched the canoe come in. At the arrival into Papeete Harbor, over half the island was there, more than 17,000 people. The canoe got to the black sand beach and there was an immediate response of excitement by everybody. People couldn’t see so they climbed into the trees. So many children got on the back that it sank the stern. We were politely trying to get them off the rigging and everything else, just for the safety of the canoe.

None of us were prepared for that kind of cultural response – something very important was happening. These people have great traditions and they have great genealogies of canoes and great navigators. What they didn’t have was a canoe. And when Hokul&a arrived at the beach, there was a spontaneous renewal, I think, of both the affirmation of what a great heritage we come from, but also a renewal of the spirit of who we are as a people today.

Hokule’a was built to accomplish an experiment in voyaging based on scientific inquiry and to participate in the celebration of the bicentennial - to be Hawaii’s contribution to America’s Bicentennial. She was not intended to ever sail again. But we recognized that we couldn't just be talking about and reading about our cultural revival - we had to live it. We had to practice it.

Another Voyage?

But Mau did not sail back to Hawai'i with Hokule'a. There had been trouble during the long sail to Tahiti on the small canoe without customary comforts. Some of the crew did not have the required discipline, and Mau quietly returned to his island in the western Pacific, leaving the tape-recorded message behind for the crew, "Do not come look for me; you will not find me." Hokule'a had to be navigated back with the help of a magnetic compass and modern instruments. This was an unfortunate turn of events: Nainoa could have already then learned much from Mau about navigating the traditional Polynesian way.

Nevertheless, a small group of dreamers, Nainoa among them, dreamed of another voyage to Tahiti where, relying on their own knowledge, they would be able to repeat the feat accomplished by Mau. In losing Mau, the Polynesian Voyaging Society had lost an invaluable teacher who could have helped the crew of Hokule'a learn the old ways. However, they tried to learn on their own the ways of the past. Nainoa was interested in navigation but had little knowledge of the stars, of navigation, of ocean currents and swells, of winds and the clouds, and the habits of birds-all providing cues to the navigator to his whereabouts and to finding land. He buried his head in astronomy books, making sense of the stars, the sun, the moon. While studying ocean sciences at the University of Hawai'i, he was teaching himself to navigate the canoe.

And the crew sailed, experimented, and learned. Once on an extended training voyage, Nainoa, navigating the Hokule'a with limited knowledge, had an experience that shook his confidence. "The moon rose in a place I didn't expect. I expected the full moon to rise in the same place the sun had risen in the morning, but it came up somewhat to the south! Why? I thought I had understood the relationships between the path of the sun and the moon fully. This just didn't make sense.

"When I got back home, I grabbed my astronomy books, but I couldn't find an answer in them-I had no teacher! I thought the planetarium at the Bishop Museum might have an answer to this riddle. They said, 'Sorry, we don't have time to help you. Try Will Kyselka.' So at 6 A.M., I called Will and said, 'I've got this problem with the moon!"'

Will, whatever he might have thought about this strange problem and the phone call at such an odd hour, invited Nainoa to meet him at the planetarium to explore the simulated heavens together. And, this is how Will, nourishing Nainoa's hunger for knowledge, became one of Nainoa's revered teachers. Will writes about how Nainoa used the planetarium to learn about the stars.

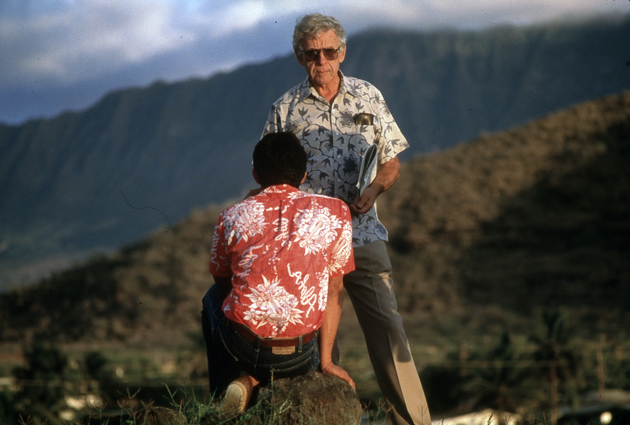

Will with Aaron Young. Photo by Monte Costa

In the darkness of the planetarium, he could see in a flash what might have taken years of observing the sky to comprehend. He had expected the sun and the Full Moon to rise at the same point on the horizon; but he found that was not necessarily so. [The planetarium allowed him to study the shift in the moon's rising and setting paths as it completes its monthly cycles.] Immediately he saw why the picture of the sun-moon relationship he had been carrying in his head did not fit the reality of the event he had witnessed on that most perplexing night at sea.

Nainoa recalls the end of that helpful visit to the planetarium; "I still wanted to learn so much from Will, but I didn't think it proper to ask him. I thought that would be an imposition, that he was so busy. But Will must have sensed my wish because he finally said, 'Why don't you come back again!' I had found someone who cared, who was willing to give up time to help another person learn!

"We spent hundreds of hours together at the planetarium. I would figure out at home what I didn't know and then come to Will at the plane-tarium with my questions. And together we would look at the different skies to find answers. Will was teaching me the fundamentals of the skies and how they can be reduced to geometry, to math, and science."

Will Kyselka paints a picture of these intense learning sessions at the planetarium.

"Canopus at the meridian," says Nainoa. The machine whirs and stars rush across the sky as I bring the second brightest star in the sky to the meridian.

"Now slow ...." Nainoa and Bruce team up to collect data, one watching the eastern horizon and the other the western for the rising and setting of bright stars. We move through the first night in ten minutes, each of them calling out the moment an important star rises or sets....

Nainoa writes in his notebook: "At 20° North [the latitude of Hawai'i], Gienah rises as the tail of Canis Major reaches the meridian. Avior is almost at the meridian when Spica and Hokule'a are rising. With Regulus at the meridian, the False Cross and Southern Cross are tilted at the same angle." (Ocean in Mind 27)

The Capsizing of Hokule'a, 1978 and the Legacy of Eddie

In 1978, the second voyage of Hokule'a to Tahiti was to take place. Nainoa was keen to learn more about the ancient way of navigation. By actually trying to navigate Hokule'a using only the stars and ocean cues as guides on this long voyage, he wished to expand on the learning gained from books, the planetarium, and the short voyages in Hawai'ian waters. The accuracy of his course was to be checked by someone with a sextant and modern instruments. Nainoa would only be given that information if they were dangerously off-course.

Nainoa hesitates and looks away. "It's only fair to mention that it wasn't all perfect and glorious. We made mistakes. I must tell you about Eddie, because he had, and still has, great influence on me; he's one of my great teachers." Nainoa tells of how Hokule'a, a few hours after leaving Honolulu harbor, capsized in the Moloka'i Channel and floated upside down, the crew clinging to her overturned hulls. For hours airplanes flew overhead between the islands but did not spot them. Fearing that they might drift ever further away from help, Eddie Aikau, lifeguard on the big surf beach of the North Shore of O'ahu and at home on his surfboard in even 30-foot waves, left on a surfboard to get help. Eddie was never seen again, Hokule'a finally found.

"Come, I want to show you something." Nainoa steps into another room and points to a picture of a young man, tanned with long hair, smiling, and looking as if about to talk with you – it is Eddie. "Eddie had this dream about finding islands the way our ancestors did. Whenever I feel down, I look at Eddie and I recall his dream. He was a great teacher. He was a lifeguard ... he guarded life, and he lost his own, trying to guard ours. Eddie cared about others and took care of others. He had great dreams, he had great passions.

"After Eddie's death, we could have quit. But then Eddie wouldn't have had his dream fulfilled. He was my spirit. He was saying to me, 'Raise those islands.' His tragedy also made us aware of how dangerous our adventure was, how unprepared we were in body and in spirit." Is it perhaps from trying to make sense of Eddie's tragic death that Nainoa has come to understand that success should not be measured by the outcome of something we do but by "reaching a new place within ourselves?"

Learning from Mau (1978-1980)

Most of all, we realized we did not know enough. We needed a teacher. Mau became essential. Mau is one of the few traditional master navigators of the Pacific left. And Mau was the only one who was willing and able to reach beyond his culture to ours.

I searched for Mau Piailug. Finally, I found him and flew to meet him. Mau is a man of few words, and all he said in answer to my plea for help was, "We will see. I will let you know." For several months I heard nothing. Then one day I got a phone call; Mau was going to be in Honolulu with his son the next day. When Mau arrived here back in 1979, he said, "I will train you to find Tahiti because I don't want you to die." He had heard somehow that Eddie had been lost at sea.

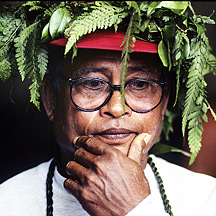

Mau. Photo by Steve Thomas

I asked him to teach me in the traditional ways. But Mau knew better. He said, "You take paper and pencil! You write down! I teach you little bit at a time. I tell you once, and you don't forget." He recognized that I could not learn the way he had learned.

[More background on Mau from the Polynesian Union speech:

Mau’s island, Satawal, is a mile and a half long and a mile wide. Population 600. Navigation's not about cultural revival, it's about survival. Not enough food can be produced on a small island like that. Their navigators have to go out to sea to catch fish so they can eat. Mau was not like me, who learned by using both science and tradition. I started at an old age, at about 21. He started at one. He was picked by his grandfather, the master navigator for his people, taken to the tide pools at different parts of the island to sit in the water and sense the subtle changes in the water's movements. To feel the wind. To connect himself to that ocean world at a young age. His grandfather took him out to sail with him at age four. Mau told me that he would get seasick and when he was seven years old, his grandfather would tie his hands and drag him behind the canoe to get rid of that. This was not abuse. This was to get him ready for the task of serving his community as a navigator.]

Mau learned to turn the clues from the heavens and the ocean into knowledge by growing up at the side of his grandfather – he had been an apprentice in the traditional way. He had learned to remember many things through chants and would still chant to himself to "revisit information."

Mau's greatness as a teacher was to recognize that I had to learn differently. I was an adult; I needed to experiment, and Mau let me. He never impeded my experimenting and sometimes even joined in.

I never knew when a lesson started. Mau would suddenly sit down on the ground and teach me something about the stars. He'd draw a circle in the sand for the heavens; stones or shells would be the stars; coconut fronds were shaped into the form of a canoe; and single fronds represented the swells. He used string to trace the paths of the stars across the heaven or to connect important points.

The best was going out on my fishing boat with Mau ... every day! I watched what he watched, listened to what he listened to, felt what he felt. The hardest for me was to learn to read the ocean swells the way he can. Mau is able to tell so much from the swells-the direction we are traveling, the approach of an island. But this knowledge is hard to transmit. We don't sense things in exactly the same way as the next person does. To help me become sensitive to the movements of the ocean, Mau would steer different courses into the waves, and I would try to get the feel and remember the feel.

Mau can unlock the signs of the ocean world and can feel his way through the ocean. Mau is so powerful. The first time Mau was in Hawai'i, I was in awe of him-I would just watch him and didn't dare to ask him questions. One night, when we were in Snug Harbor, someone asked him where the Southern Cross was. Mau, without turning around or moving his head, pointed in the direction of a brightly lit street lamp. I was curious and checked it. I ran around the street light and there, just where Mau had pointed, was the Southern Cross. It's like magic; Mau knows where something is without seeing it.

I spent two Hawaiian winters with Mau. In the summer, ninety-five percent of the wind is trades, so it's easy to predict the weather. Tomorrow is going to be like today. But in wintertime you have many wind shifts. When I had spent enough time with him, I realized that he was not looking at a still picture of the sky. If you took a snapshot of the clouds and asked him, "Mau, tell me what the weather is going to be," he could not give you an answer. But if you gave him a sequence of pictures on different days, he would tell you.

He said, "If you want to find the first sign of a weather change, look high." He pointed to the high-level cirrus clouds. "If you see the clouds moving in the same direction as the surface winds, then nothing will change. But if you see the clouds moving in a different direction, then the surface winds might change to the direction the clouds are moving. That's only the first indication, but you don't really know yet. If clouds form lower down and are going in the same direction as the clouds up high, there is more of a chance that the winds will change in that direction. When the clouds get even lower then you know the wind direction will change."

Satellite technology was in its infancy then, and many times Mau's predictions would be right and the National Weather Service would be wrong.

He used the same clouds that we use to predict the weather--mare's tails, mackerel clouds. But in his world, he practices a kind of science that is a blend of observation and instinct. Mau observes the natural world all day. That's how he relates to nature. There are no distractions, so his instincts are strong.

In November of 1979, Mau and I went to observe the sky at Lana'i Lookout. We would leave for Tahiti soon. I was concerned-more like a little bit afraid. It was an awesome challenge.

Then he asked, "Can you point to the direction of Tahiti?" I pointed. Then he asked, "Can you see the island?"

I was puzzled by the question. Of course I could not actually see the island; it was over 2,200 miles away. But the question was a serious one. I had to consider it carefully. Finally, I said, "I cannot see the island but I can see an image of the island in my mind."

Mau said, "Good. Don't ever lose that image or you will be lost." Then he turned to me and said, "Let's get in the car, let's go home."

That was the last lesson. Mau was telling me that I had to trust myself and that if I had a vision of where I wanted to go and held onto it, I would get there.

Year after year he came and took us by the hand. He cares about people, about tradition; he has a vision. His impact will be carried beyond himself. His teaching becomes his legacy, and he will not soon be forgotten.

The Voyage to Tahiti (1980)

Finally, in the Spring of 1980, the crew of Hokule'a decided they were prepared – in spirit, in health, and in seamanship – to try once more to "raise the islands" as they had set out to do two years earlier with Eddie. Nainoa was now much better prepared to find the way without instruments. Mau would be there but would only step in if he felt there was serious danger to the canoe or the crew. And this time, there was an escort boat, the Ishka.

On the significance of the 1980 voyage to Tahiti (Polynesian Union speech):

The difference on the trip in 1980 was that the round-trip trip was guided by and captained by people from Hawai'i. For our culture to really be alive, we recognized that we had to practice it ourselves. Mau Pialug made a fundamental step. He became, instead of the navigator, our teacher. An incredible feat, considering he could barely speak English. He was the one who came to Hawai'i and made this enormous cultural jump. I believe that the great genius of Mau Pialug is not just in being a navigator, but that he could cross great cultural bridges and help us ... like taking children by the hand ... find our way on the sea. All of this came from a very powerful sense of caring on his part.

Mau. Photo by Monte Costa

At the end of our voyage, Mau told me, 'Everything was there in the ocean for you to learn, but it will take you 20 years to see.' Mau is right. For me to learn all the faces of the ocean, to sense the subtle cues, the slight differences in ocean swells, in the colors of the ocean, the shapes of the clouds and the winds, and to unlock these cues and glean their information in the way Mau can, will take many years more. Initially, I used geometry and analytic mathematics to help me in my quest to navigate the ancient way. However as my 'ocean time' and my time with Mau have grown, I have internalized this knowledge, and my need for mathematics has become less. I come closer and closer to navigating the way the ancients did.

On The Voyage of Rediscovery, 1985-1987 (Polynesian Union speech):

After we got back from Tahiti, we started thinking about what to do and where would it be important to go to? Other parts of Polynesia have great canoe traditions. We wanted to take Hokule'a to these different places and meet these people. And so we started planning for the Voyage of Rediscovery ... rediscovering ourselves. We know that there were certain migratory patterns that had to take place to colonize that great nation of Polynesia. There were at least seven major legs. This is the route. It was to go from Hawai'i down to Tahiti, through the Cook Islands, down to Aotearoa, up to Tonga and Samoa, and then against the tradewinds. (The thing that Thor Heyerdahl said that couldn't be done), to the Cook Islands, back to Tahiti, up to the Marquesas, then back to Hawai'i. A voyage of 16,000 nautical miles. It was driven by this notion that reviving our culture is important to our people. Keep in mind, we didn't know anybody in most of these islands. But we just believed that it was important to take the canoe to them.

Hokule‘a, 1985-87

The trip from Hawai'i to Aotearoa in 1985, like other voyages, was created out of dreams. The dream was to go to this place called Aotearoa ... land of the Long White Cloud. We started two years before the voyage, just in the planning and the preparation. To cross 1,700 miles from Raratonga to Aotearoa, even though it's shorter than the trip from Hawai'i to Tahiti, is very different. We were leaving the tropics and going into the subtropics. We were going into different weather systems that we were not accustomed to. It was the first time that Hokule'a would be going into much colder water, different environments, much more complicated weather systems.

We took two years to plan. What is the strategy? How are we going to navigate without instruments? One of our real important places to "hit" were the Kermadec Islands. Because if we could find these islands, we would know where we are. Instead of this trip being 4,500 miles from Hawai'i, through Tahiti and the Cook Islands, our trip would be only 450 miles.

As Aotearoa is so much father south than Hawai'i, the star patterns relative to the horizon are very different. We needed to go and study those star patterns. I knew that from an academic point of view, I had to train this way. But I also knew from an instinctive point of view, I needed to see this land before I came on the canoe. The only person I knew in Aotearoa, prior to going down, was a man that you all know, Mr. John Rangihau. And Ilima Piianaia was the one who introduced me to him. And John Rangihau, for those in Hawai'i who don't know, is very respected - - one we would call a kahuna, one who possesses great mana. I asked him in my kind of foolishness, "Mr. Rangihau, I need to go to Aotearoa, and I need to study the stars in the northern part of your island. I looked at a map, and I located a place called Tereinga. It has a light house. Can you pick me up and drop me off there? I'll live in the light house; I'll take my own food. And when I'm pau, can you pick me up?" had no idea what I was doing. I knew no one but him. And he said, "okay, I'll do that."

So I flew to Aotearoa. I was 29 years old. Went through customs and no John Rangihau. I remember these moments, very special moments. Remember, I didn't know anybody. All of a sudden I see this very friendly lady with a banner with my name on it. And she's waving it above her head. And I was saying, oh boy, things are not going the way I throught they would. We went outside in the parking lot, and she put me in the back of her car. She had mattresses and pillows in back of the car to make it into a bed. And that was just one of the many, many gestures of caring that I had there. I was thinking, okay, we're going to go to Tereinga. This place with a light house. That's all I knew. And she said, "Oh no, we're going to someplace else. We're going to Aurere. But they didn't know where it was. So we were going around Mangonui for a while, then we finally went to this place called Aurere."

This connection to people, this building of relationships was probably the most powerful thing in all of my voyaging. Hector, Busby was confused as to why this small little Hawai'ian was going to be with him to look at the stars. But when we talked about the canoe, he understood. He said, "I know what you're going to do is important. Do what you must do, and I'll help you all the way." You see, from that message, voyaging is not about one person. It takes many, many people. This connection with Hector ... began a relationship that changed my life.

Hector Busby. Nainoa is half visible over Hector's shoulder.

It enriched it in a way that I could never imagine. I went back home renewed and studied harder. There became a much greater purpose of going to Aotearoa than just for science and culture. It was about connecting people. We went down to Rarotonga. Hector was there. We did not have the kind of weather conditions we needed to go. Safety was a priority. We had tropical cyclones near Rarotonga, and New Zealand was experiencing a late winter with their subtropical lows. The two worst conditions we wanted. I was frankly afraid. I was afraid to go because there were so many people's lives at stake. And I was in my early thirties, and I did not have the confidence and the maturity to be handling that kind of pressure. My dad said, "You make the best decision you can make, and we will all follow that." And Hector said, "Don't worry. When you go, you will be there because your ancestors are with you." Two very powerful concepts from those that I would consider parents to me. And we did leave. And Rarotonga in the stern took about six hours to have her go below the horizon. It was an incredible, incredible voyage, the special moments. We had an incredible crew. A crew of common people, bonded around a common vision, from all walks of life.

One special moment -- we were trying very hard to target the Kermadec Islands. The night before this photograph was taken, we saw the stars in a very unusual pattern that gave me a lot of confidence that I knew where I was. Because of the clarity of the sky, I held the direction west. That's where I thought the islands were. The next day because we were looking into the sun which made the water sparkle, we didn't see a pod of whales coming .. . sperm whales. I guess there were about 18. We sailed right into the middle of the pod. I don't know why, but one of the whales -- I guess it was a mother who became separated from its calf, turned from the north, from our starboard side and swam at us with such force that she raised her whole head out of the water. And came right to the hull of the canoe. And at the last moment, turned down and turned its tail and -- instead of ramming us, which would have permanently damaged the canoe, she just kind of nudged us to the south. My scientific background, that had no value. I was just lucky we were still floating. And we kept heading towards the setting sun. That afternoon, a squall came out of the north. Not an ordinary one. It was like this, where the cloud touches the water. And so was the lightning. Fork lightning coming out of the south, our winds dropped, the clouds came upon us. And then I said, lets turn south. Forget the Kermadec Islands, this is too dangerous since we're at the highest part of the water and the lightning becomes very dangerous. We headed south and we sailed in this mist. No storm, but in a mist. But we just sailed, not towards the stars, but away from the lightning in the north. I gave up this notion of finding the Kermadecs because I felt we were going the wrong way.

Next morning, I was sleeping from exhaustion and was not even awake. We had run right into the Kermadecs through the night. We had passed one of the islands. And these are the islands right here, the Kermadec Islands. It was like a gift. Sometimes the navigation is far out of our own hands. Other things guide it. From my background and from science and math, it doesn't make a lot of sense, but in my intuition it does. And these special moments are what make voyaging the most important. And from there we knew where Aotearoa was. The rest of the voyage was relatively easy. You see us guys in this gear? Survival gear, we're at 30 south. We, throughout the whole voyage, talked about how incredibly strong and the quality of endurance of Maori people. Consider that they occupied islands south of Aotearoa at 60 degrees south. That's equivalent for us to go sail to Alaska without foul weather gear. And that is not something that we could do. I tried my hardest one night to experience the cold, and we were only halfway there, 30 degrees south. We remember the chants of legends and genealogies speaking of white floating islands and birds that fly on the water, icebergs, penguins. We were in awe of the strength of those ancestors.

We arrived in Aotearoa. I remember this moment with Stanley Conrad from the North Land, chosen by his people to represent Aotearoa. Stanley came as a young man, and he performed extremely well. And his tremendous concentration on this land. Because I believe that Stanley Conrad came to the canoe in Rarotonga as a boy, and he arrived home. And this home would be defined, yes; as a physical place. He crossed 1,700 miles, but he crossed it in a canoe like his ancestors. And that notion of home is something that was very deep inside of him. And that he just sat there and watched. Said nothing. I think because the experience was too powerful for him. It certainly was for us. When the Maoris greeted us outside in the swells, we heard them chanting before we saw them. And then we could see the canoe rise on the top of the crest, and settle back down in the trough. It was awesome.

Waitangi Canoe. KS Archives

To me, it was such an important time for Stanley standing there in the rear as for us. The joining of two canoes was the joining of two cultures. These two cultures have common ancestry. This is not a union of people. It's a reunion. And these experiences have made the voyages so important. And there was Hector Busby fulfilling his promise that he'll be there all the way. Hoping and praying for us like others. Like any parent would. was very happy to see him that day, because we completed the dream that he said that our ancestors would support.

And then we were invited to this special, special occasion, to the marae at Waitangi. And we were quickly educated that the marae houses wellness for your people. We watched grandchildren and grandparents dance together and sing together. We were greeted in the traditional way because that was the way it's supposed to be done.

We understood that in these houses, it houses not just people, but it houses the genealogies, how you trace your ancestry back to the actual canoe that brought you to Aotearoa. And in my life, until Kamaki started to do his work, and renew the power of our genealogies, I couldn't do that. And I felt very disconnected from where I came from. I can see how close and connected you are to your ancestry. That is very powerful. The marae houses not just your past and where you are today. Because you are connected to the past, I believe that it's much easier to see what kind of future you want to voyage to. This was another part of our own work towards renewal.

And Sir James Hinare got up and spoke. He said a number of things. He said that you've proven that it could be done. And you've also proven that our ancestors had done it. This was a very special moment for him, a very special occasion, and he laughed and he cried. I recognized from him that we already come from a powerful heritage and ancestry. The canoe, on its voyages, is just one instrument to connect that. Sir James Hinare also said an incredible statement ... because the 5 tribes of Taitokerao trace their ancestry, their family, from the names of the canoes, and because you people from Hawai'i came by canoe, therefore by our traditions, you must be the sixth tribe of Taitokerao. We didn't know what to make of that, such a powerful statement. But I do know -- remember in my point of view, the most powerful things are these relationships. In a few sentences, Sir James Hinare had connected us to you. And he said that all the descendants from those who sailed the canoe are family in Taitokerao.

When we were leaving Aotearoa, again, we had very bad weather conditions. Conditions where we couldn't leave on schedule. We had to wait 22 days. Hilda, Hector Busby's wife, said, "When you're in my land, I am your mother and you are my children. Because of that, children need to be cared for. So I will stay with you all the way." Twenty-two days we were housed. Twenty-two days she fed us three times a day. Twenty-two days she washed our clothes. We were cared for like family. I believe that much of the definition of my quality of life is determined by the kinds of quality relationships I have with others. I believe that to consider this notion to sail to Aotearoa as a dream, and to go there as a single individual to sleep in the lighthouse, I could never have imagined how important it is to be with people. And this is why I think this conference is so important. It's sharing ideas. Sharing hopes and aspirations for a better future.

On Samoa to Tahiti, 1986 (Hui Lama speech):

Thor Hyerdahl had said that it was impossible to get from western Polynesia to eastern Polynesia - to Tahiti - because of the easterly trade winds. He thought that vessels could not tack against it. We trained for two years and we waited for the most optimal weather patterns. We cut down our crew. We cut down our water. We made the canoe light so that it would perform better. We hoped to make the voyage in 35 days. The key was the preparation. We went to Samoa and waited for the weather. We had planned for a 35 day voyage, the longest ever, and we did it in seven days.

On The Voyage to Rarotonga, 1992 (from the Hui Lama speech):

The Pacific Arts Festival in 1992 was the joining of Pacific island nations every four years to celebrate the visual and performing arts. It was selected to be held in Rarotonga in 1992. The prime minister of this historic island said, "let's dedicate it to our historic voyaging ancestors" and he asked that each island group bring a model of their canoes to display. And somebody said, "no, we will sail our canoes." And you know Polynesians, how they are! That challenged everybody else. So they decided to build their canoes. They called Hawai'i and asked for assistance and it was a great opportunity for us to pay back - in a small way - the kindness we found all through the South Pacific. They took care of Hokule'a like it was their own. It also gave us the opportunity to move into a new area - education. We recognized the importance of education in the revival of our culture. In the end, seventeen canoes participated.

We asked that each canoe bring a stone from their native lands.

It was the beginning of a sharing of knowledge which has now become Pacific-wide. I want you to know that when they were planning the Pacific Arts Festival two festivals before this, they did not invite Hawai'i because they thought that the Hawai'ians had sold out their culture to tourism.

On The Building of Hawai'iloa,1990-1995 (Polynesian Union speech):

It took five years to build a voyaging canoe out of native materials. Hokule'a is made mostly of modern materials. We started in our koa forests and ended up finding that in the last 80 to a 100 years, 90% of our koa trees have been cut down. The ecosystems which once supported this healthy forest is in trouble. We could not find a single koa tree that was big enough and healthy enough to build one hull of a canoe.

We went elsewhere; we went to Alaska. We knew trees from the Pacific Northwest drifted to Hawai'i, and our ancestors cherished them. We asked the Alaskan native Indians, people we didn't know, "Can we have two trees to build a canoe?" They didn't know us, but they responded immediately without hesitation and said yes. You tell us what you need. So we told them the specifications. And they said they would search. And they did, six weeks into the most remote parts of their forests. And then they called us up and said, we have the trees of your specifications. We're not going to cut them down unless you come up here and tell us it's okay. Because we believe that our people are connected to the natural environment, that the trees and the forests are family to our people. And we're not going to take the life of a family member unless we know this is what you want.

So we flew up to Alaska. We got a helicopter from Ketchikan and went west 80 miles to this remote forest. This was exactly what we wanted in our dimensions. When they asked us, shall we cut these trees down, I told them no ... we can't do that. Everybody got real quiet. I couldn't explain myself. We went back on the helicopter, no one talked. We flew back to Honolulu. The trees remained in the forest. Something was wrong. I didn't know what it was. I talked to Auntie Aggie Cope. I talked to John Dominis Holt, our elders who were on the Board supporting this project to build the canoe called Hawai'i Loa. Why did I not cut the trees down? It was because for us to take the trees out of Alaska, to some degree, we're walking away from the pain and the destruction of our forests. We could not take the life form of another tree unless we dealt with that abuse in our own homeland. The answer was clear. Our elders told us, you know what the answers are and it's very simple. To deal with the abuse you need to renew it. The only answer before you cut down somebody else's trees is to plant your own. We started programs at Kamehameha Schools, and now we've now planted over 11,000 koa seedlings. So that in 100 years, the next two generations, we'll have maybe forests of voyaging canoes.

Then we went back to Alaska, and we cut the trees down. The Alaskan people are very interesting. They said, you take these trees. It is a gift to you, but do not ask us how much it cost. And do not ever bring them back. Because then it's not a gift. We estimate the cost to be about a third of a million. They cut them down, they took them out of the forest, they shipped them to Hawai'i. Consider these trees. This is in the Bishop Museum. These trees were -- one was 218 feet tall, 418 years old, weighed 100,000 pounds.

Now what do we do? This was what the project was about. It was finding a focus, a vision of building a voyaging canoe that people could feel was special enough to bring all their resources together. Because we knew for us to do this like in ancient times, it would take the effort of a healthy community to build a voyaging canoe. We brought in the best --Wright Bowman, Jr., whom I consider the best canoe builder in Hawai'i. His job was to pull a 4,000-pound hull out of a 100,000-pound tree.

Bow carving the spruce log to shape a hull for Hawai‘iloa

We needed 10 lauhala sails. We asked our weavers to help us build our sails, our native weavers, and they told us, "No, we're not going to do that because the job is too big, and if we make a mistake, maybe you'll die." They didn't want to be responsible; that's the old way. We asked them to please try. And after about a month of coaxing, they said "Yes, we will try." These two ladies, Mrs. Nunes and Mrs. Akana, made the first sail big enough for a voyaging canoe, probably in 600 years. The thing that impressed me most was that it took them 13 months. We estimate about 280,000 weaves for the sail. When you take up the panels and put it up against the light, you can barely see a pinhole through it. These two ladies had reached what we felt we were searching for the most - - that is pursuit of excellence in our people, in our traditions, in our heritage. And it's because of the great concern they had for our well-being that they put in so much care into weaving those sails.

The building of Hawai'i Loa brought together people -- we estimate half-a-million man hours were spent building the canoe. No metal parts, three miles of lashing. In the end it was a journey of people coming together because they shared a common vision, common values. They worked together for something they believed was special, not just to themselves but to their whole community.

We then sailed and trained for two years. We sailed 2,000 miles in Hawai'i before we left. We made huge mistakes. We took the canoe out and sailed it. Our first day we almost got run over by a container ship outside of Waikiki because we couldn't turn it around. We recognized we made some big mistakes in our computer design and took it back out of the water. There was an imbalance between the hull design and our sails. The only answer was to turn the canoe around. We took all the three miles of lashings off, relashed it, sailed it backwards, it worked perfect.

Hawai‘iloa was not the only canoe being built. Hector, on his own and I think it’s through dreams, believed that Aotearoa needed their own canoe. He took the lives of two kaure trees and built Te Aurere and started on this great journey of reviving the traditions, thereby reviving the dignity and the pride of a culture, a people. Te Aurere was part of a whole revival throughout Polynesia.

On The Voyage to the Marquesas, 1995 (Polynesian Union speech):

The voyage in 1995 was not just about Hokule'a , but rather the children of Hokule'a -- Hawai'i Loa, another canoe called Makali'i, two canoes from Tahiti, two from Rarotonga, and Te Aurere from Aotearoa. We all sailed to a place called, Taputapuatea in Raiatea ... a place of great teaching in navigation, the most appropriate place to start this voyage that would take these canoes to the Marquesas. Some, believe it is the homeland to the first people to come to Hawai'i.

Hawai‘iloa sailing off of Honolulu

We trained navigators for five years. Recognizing that for our culture to be strong, if navigators are an important part of that, then we have to build strength in our numbers. These are the six canoes that made the voyage from the Marquesas to Hawai'i, over 2,200 miles of open ocean. Five of them, navigated by navigators from their own islands, trained to sail them in the ancient way. These colors that you see here correspond to the routes that they sailed.

We put transponders to locate positions of the canoes for documentation and safety. We staggered the departures from the Marquesas, so that each canoe was by itself. If we were all together, one canoe would be leading, everybody else would be following. So everybody sailed on their own. If you look at these tracks, it's interesting to note that the navigational system works. But what's more interesting, to me, is that the process of education can work to accelerate learning when you combine tradition and science, and when you have people who are motivated -- compassionate enough to work hard and commit themselves to a difficult task as this is.

I think this is a very powerful image of Te Aurere sailing off Honolulu; she was joined on that day by the five other Polynesian voyaging canoes that had made the journey from Nukuhiva to Hawai'i with her:

This slide to me is about fulfillment of dreams. Not just dreams, but powerful beliefs that what you're doing is important, it's worth the commitment -- that even though you're committing to the risk of maybe even death. I dedicate this to Hector Busby ... his vision, and his commitment to his people. I've seen the struggle. This is not an easy thing to do. And I honor him with this simple little image of our home and his canoe in our waters.

On the West Coast and Alaska Tours, 1995 ( Polynesian Union speech):

We took our two canoes to Seattle on a Matson ship. Hokulea went south to educate. There are more Hawai'ians living away from Hawai'i than are living here. And they've made those choices because of many reasons. But you talk to these people. Their heart and their spirit is in a place that they always call home. Their house, their residence may be here. But their home is in Hawai'i. We couldn't bring the 185,000 people back to Hawai'i, but we could take our canoes there. Hokule‘a sailed down this coast to do what you are doing today. To connect. To build better relationships, to share ideas.

Hawai'i Loa went to Seattle and then went north to Alaska, to an island right over here called Shelikof. We visited 20 different Native Alaskan villages.

Hawai‘iloa arrives in Juneau, 1995. Lilikala Kame‘eleihiwa chanting to the welcoming crowd.

We took Hawai'i Loa there on this 1,000-mile journey up the coast to thank them, and to let them, more importantly, know that we did not abuse the gift that they gave us when they cut down those trees. The only way we could do that was to take the canoe to them. We weren't giving it back. We were showing to them what was already theirs. It was an incredible voyage.

Alaska is rich in resources. It has 500 times more land than we have in Hawai'i, and half the population. The people are very healthy because they still can sustain themselves within the resources of the place that they live in. I thought the people were very different. They come from a different place, speak a different language. And from my, I guess, ignorance thought, that we were very different people. I was wrong. These people share the same kinds of concerns and hopes and aspirations as we do. They believe that it is very important for the health of their people, to rebuild their culture, to rebuild their traditions. The canoe coming there was again a vehicle to connect people.

On the Significance of Voyaging in his life (Polynesian Union speech):

Our crew and I sailed with about 135 of them. Common people. They do uncommon things. On the Hokule'a, I had the privilege to be with these people, about 750 days. Never heard a loud argument. Never heard somebody raise their voice. And it's because these people know they're involved in something special. They represent more than just themselves and their families and their community. They represent the pride and honor of a whole nation, and they're simply not going to not fail in reaching their destination. Under the worst living conditions I've seen the best in humanity. I've been honored to be with these people. The canoe itself is a vehicle, this tool of incredible learning. And it's like going to Aotearoa. It takes you as a platform to very special places, very special moments, meeting very special people in a very powerful way. Our people and those who come here should know the richness of our heritage. And not only know that, but respect it. If we're to protect what we believe is special about our islands, we have to educate our people as to why its special. These canoes are just a mere fraction of what's valuable in these islands. And I just am very glad to be a part of that ... and our islands.

Even though we can sail two years in the South Pacific, we never feel the canoe and the crew are home until they see the image of our islands when it rises out of the sea. This is Mauna Kea, our highest mountain.

And we call that like our ku‘ula. It's our guardian. Because we can see it the farthest away. The arrival into the Hawai'ian Islands -- been on the canoe five times and every single time it's the same. Our crew -- normally when there's high levels of achievement made, people jump up and down and they scream and yell and everything else. Not on this canoe and not on this image. Everybody's silent. Nobody says a word. And I think it's because ... when they sail home, initially there's a response of relief because the danger is over. The crew and the canoe is safe. But there's also the very powerful sense. It's like a new definition of what home is. That to risk their lives, to bet their families that they will make it back, to take the time off from their work, is far outweighed by what they represent. This new definition of home is part of the renewal that we need as a people to be able to respect the place we come from, and therefore respect ourselves.

And the ocean. For me. It's interesting. I guess -- I don't know how to put this, but as a Hawai'ian in this complex, complicated, somewhat foreign world that I find myself, I sometimes have very difficult time seeing a picture of who I am. Does that makes sense? I don't know who I am sometimes in this world. But I know that picture very clear when I'm on the ocean and when I'm navigating. Because the ocean keeps you honest, and it's governed by very simple natural laws.

It can be as tranquil as it can be, and it can just take the life of those who are unprepared. When I'm navigating, I can step in through these moments -- and they're just moments of layers of time, like a window into our past. And it's like you and your maraes. I get connected somehow, much deeper than what I think, deeper into where I feel spiritually. That for me has been a great teacher in terms of my sense of what's important in life.

I really believe that we are a product of our experiences. We are a part of the influences of things that we go through our lives, and we on the canoes recognize that we come from very, very special experiences that made our lives very special. But you know what? That's not true for all our people. If you take a look at the socioeconomic and the health indexes and statistics of our time, not all our people have those great experiences. Our people are in trouble. We die younger, Native Hawai'ians, we die younger. We make less money. We have more people in our prisons. And we are less educated in this world. Why is that? Why would such a rich people, such great explorers, the best in the world, 3,000 years of evolution -- not just exploring on canoes, but living in a healthy, balanced, sustained place. What happened?

I don't understand it all, it's way beyond me. Something happened in the last 219 years, with the introduction of relationships from the outside. I want to ask you to consider this thought. One of the things that happened to our people is that their population declined. Take a look around and count 20 people. The projections suggest that there were 800,000 pure Hawai'ians prior to the European arrival. Over 100 years later there's only 40,000. That means that of the 20, 19 died.

Queen's Hospital was built to stop the dying race. It was built with a vision to take care for its people. It was built for the challenge of its time. But then why, today, even though our population's numbers are rising, is our health statistic so poor. I think when the outside comes in and dominates a culture of people, you end up with cultural abuse. And we know the effects of abuse on a single individual. And how it degrades one's self-esteem, how it lowers the immune system. It's not very hard to understand why our people would tend to be the most unhealthiest race in Hawai'i, than any of the other races in its own homeland.

What do we do? I think we do what we are doing. I think good things, incredible things are going on. I think that it's very simple to me that if the abuse is the problem, then rid the problem. And replace abuse with renewal. This is what this conference is about. This is a part of so many people's work to renew the pride and the dignity of our people. Make them strong so they can have the will to guide their own lives. I'm not trying to minimize how difficult that task is. I do know that it's going take the work of many.

This is a very special slide to me:

This is Jacko Thatcher. The individual that was chosen to be the navigator of Te Aurere. They did not choose a real good seaman. I think in the wisdom of the people that made the selection in Aotearoa, they chose an educator in order that he would teach their children. I remember training Jacko, because of his lack of experience, he was not very confident. He was very afraid. I would always feel this sense of uncomfortability. He did not think he could make the voyage. And yet he always said, "I'm willing to try." This slide is very interesting. To me, it symbolizes pride in a non-vainful way. It's a renewal of oneself. This is Jacko Thatcher doing the haka, his traditional dance on Hawai'ian soil, when he brought Te Aurere to Hawai'i, guided by the stars. There were two people that have always influenced my life in different ways. One is Kenny Brown. He says you want to help your people strengthen their spirit. And my dad would say, you want your people to be healthy, raise their self-esteem. And I didn't know till recently that they were saying the same thing. We have to have our people be able to believe in themselves and be strong enough to do that. And it's from these people that I understand that in some way voyaging, even though it's just a fraction of all the work that needs to be done, is connected to health in a very spiritual way. It's just a great privilege to be able to be around these elders who have the wisdom to help our generation do the work. When you have healthy individuals, you end up with healthy families. This initiative of healthy communities come from healthy families.

At the Kualoa homecoming, people came together. This is healthy. Just wondering where do we go. I don't know. I think that the work you do is kind of like the stuff that we do. We need a common vision which we can attach all our hopes and aspirations to. We need to have common values to keep us steering in the right direction towards that destination. Because in the end, as individuals, we will not be able to do very much. Together, we can do much more. It is critical to the health of our people. Our part in the Voyaging Society working with Queen's is to take what we know, our experience, what we can do, things that we've learned on the ocean, and go influence our children. If we're to say that the ills of our society is because our people have been abused by society, my simple thinking is that we need to renew that with nurturing, caring influences. Somehow we've got to find a way that we can replace the abuse with caring. That make sense? Think what you'd change. I don't think our people are necessarily sick. I think it's the parts of our society that influence sickness.

On Planning for Rapa Nui 1998 (from the Hui Lama speech):

On our voyage to Rapa Nui we are going to make five legs, change the crew five times.

Moai (stone images) on Rapanui. Photo by Sam Low

Right in this area here, near the equator, it's called the Intertropical Convergence Zone. The Doldrum area. Very cloudy. Going to Tahiti we just sail down there as close to the wind as we can. And this is a problem. But on the voyage to Rapa Nui we (are going to Nuku Hiva so) we have to go this more distance upwind (to the east) to the Marquesas and this more distance upwind to the island of Mangareva. The reason that we have not yet made the voyage to Rapa Nui is not that we didn't want to, but we didn't know how. We have to go 1400 miles directly into the wind. Going downwind would take us about 12 days or so. Multiply that by five (because of tacking) and now you are up to sixty days. How in the world could our ancestors have done this? We are going to the land of the people who I think were - if we assume that the colonizers of the largest nation on earth were the greatest explorers of all time - this particular leg had to be the most difficult one of them all. I go there in great honor of the people who found this place.

To go up wind we have to tack and it takes about five times more time to get upwind than it does to get downwind. You got to know your crew. What can they do? What can they not do? How much can you push them? What is the edge of human endurance? These voyages are not easy trips We have to get Hokule'a to sail closer to the wind than it normally does. In drydock we reduced the weight of the canoe by about 4000 pounds. She's lighter, will sail harder into the wind.

Going down to the Marquesas. This is a navigator's nightmare here (in the doldrums). We have always tried to exit this as fast as we can but now he is going to have to stay in there - whatever it takes - to get up (into the wind) that distance to the Marquesas. It's not an easy task. Then tack down to the Marquesas and change the crew. Then on to Mangareva - we have got to get this easting again, maybe two hundred miles, not too bad, probably take us five days. Then we tack down to Mangareva and avoid this shield of very dangerous atolls (Tuamotus). Then we are going to change the crew again and begin this next trip to Rapa Nui. Let me put it this way, if you mathematically figured it out, if you took the canoe's performance and factored in the wind conditions, the probability of getting there is near zero if you just try to tack it. So we are going to make this incredibly complicated voyage. We are going to take the smallest crew ever. We are going to cut our food rations in half. We are going to cut our water rations in half. We would ordinarily take 400 gallons on this trip but we are going to take 210. Just to cut the weight down. We will depend on catching rain. Increase speed, go higher into the wind. We get to Pitcairn and will go into Bounty Bay - if we can anchor. But if the wind is in the wrong direction it is not a safe anchorage.

Depending on the wind conditions, we have two strategies. One is to try and tack it against the southeast trade winds and we would need to get some very favorable wind shifts in order to do that. But this is a long brutal job. Going into the weather all the time. It's rough on the canoe. It's wet. The other choice is to get to Pitcairn and go south. Go south of the trade wind belt and get through what they call the horse latitudes into the counterpart of the trade winds some place below thirty (degrees south) where the winds shift westerly so now the winds will be coming behind us. So our idea is to take about 6 to 8 days to get through the horse latitudes and sail across here five hundred miles and then tack back up north. [The second strategy was later abandoned as too dangerous, as the westerlies below 30 degrees south are generated by winter storms that could overwhelm the canoe.]

Now, what is so fascinating about Rapa Nui to me is that it is smaller than Ni'ihau, lower than Ni'ihau. How in the world did our ancestors do it? They were the greatest navigators of all time. Sailing across there (down low around 35 degrees south) you can imagine that being able to judge speed and time is critical. We want to come up to a point that is the distance equal to that between the big island and Niihau?. We know the Hawai'ian Islands. We have a feel for that distance. We want to compact? them and make sure that we didn't sail past that island. And then set up a series of tacks using the stars to tell latitude and tack enough so that we will cross this whole ocean area in a search pattern.

Again, there are four parts of this, one to get to Pitcairn- to get as close as we can to Rapa Nui from a known spot that we will leave from. So at Pitcairn we can forget all that we have memorized up to then, tack south, get into the westerlies, sail east, turn up (north), and get to a point one Hawai'ian Island chain distance from our target and then search. We think it will take a long time. I don't even want to predict how long it will take. But it is going to be quite a challenge.

The two biggest issues that we have never dealt with are sailing into the wind for such a long time and the tiny target that we are trying to hit which will force us to employ a search strategy that we have never used before. As we sail west it is important to know when to turn, if we turn too soon we will end up tacking into the wind and it will take too long, if too far, we will be sailing toward South America.

On Depature for Rapanui (September 20, 1999, interview with Sam Low, documentor on the Rapanui Voyage):

In the last few days, I have just tried to get quiet, calm and to study--that is how I prepare. I am thinking all the time about home, about the voyage, the weather, the crew, about what we have to do to make this work.

Sailing east for Rapanui. Photo by Sam Low

I think about home a lot because that's why we do this. We love our homes, we love our people, we love our culture and our history, and we want to strengthen them--this is our opportunity, our chance to do something to support all those who care about these things. I want to thank all the people who gave so much to allow this voyage to take place, but who are not here now. They allowed us to take the risk, to do all of this.

I want to thank all the families and children involved for giving us the chance to go. This voyage is about people--it's about all our people.

When I think back on my life, it's clear that I had no way of knowing that I would be here now doing what I am doing. When I began studying in school and gaining knowledge, sometimes I doubted the importance of that effort. But it's the knowledge that I gained with the help of so many taeacher that is allowing me to do what we are about to do.

So I just hope that all our children will keep on pursuing knowledge because none of us know where we are going, but at some point in our lives, that knowledge will allow us to jump off into the unknown, to take on new challenges, and that's what I consider before every one of these voyage...the challenge. Learning is all about taking on a challenge, no matter what the outcome may be. When we accept the challenge we open ourselves to new insight and knowledge.

When we voyage, and I mean voyage anywhere, not just in canoes, but in our mind, new doors of knowledge will open. and that's what this voyage is all about..it's about taking on a challenge to learn. If we inspire even one of our children to do the same, then we will have succeeded.

On Finding Rapanui (October 10, 1999, interview with Sam Low)

The voyage is pau and this gives me almost an empty feeling. But everyone should be proud of this accomplishment. We have traveled to the last corner of the Polynesian triangle and that achievement is not just ours - it belongs to everyone who has donated a portion of the millions of man hours spent taking care of the canoe over the almost 25 years since her creation.

Sailing off of Rapanui

We worked hard to prepare for this voyage but it was not just academic preparation and physical training that got us here. It was my plan to continue sailing southeast and tack back northeast at sunset - but the wind shifted northeast and if we tacked we would have been going back the way we had come. So instead I decided to follow the wind around and in the morning the island was off our port bow. The wind brought the canoe here. It's about mana. Hokule'a has latent, quiet, sleeping mana when she is tied up at the pier in Honolulu. But when the canoe is sailed by people with deep values and serious intent the mana comes alive - she takes us to our destination.

The mana is inside all of us. It's tied to our ancestry and our heritage. Sometime, in the press of daily life, we neglect it. But when we come aboard this canoe and commit our spirits and souls and lives to a voyage like this one, I think we all feel it. I know I do. This is a very privileged moment for all of us - we have stepped inside that realization of mana on this voyage.

When we go back to our special island home, we need to remember this moment. Mana comes from caring and commitment and values. We malama our canoe and she takes care of us. When we return to Hawaii we need to remember to malama our islands just as we do this canoe. We need to commit ourselves to the values that give life meaning. This canoe is so special - and our island home is also very special - if we learn to care for our land and our ocean they will also take care of us.

On Mau's Legacy (Polynesian Union speech)

When I did my first voyage and came home in 1980, Mau said everything you needed to know about navigation is in the ocean, and it is all there for you to learn. But because of your age, you'll never see it all. He said if you want Hawai'i to have a navigator that knows it all and sees it all, send your children.