Twenty-Five Years of Voyaging, 1975-2000

Nainoa Thompson

The Polynesian triangle covers ten million square miles of water- in sheer size the largest nation on earth. The people who explored and settled this nation were great ocean explorers--the best of their time. Consider that there is a connection to South America-- the sweet potato--maybe it was brought from South America by Polynesian voyagers who went there and returned. We also know that halfway across the planet, in the Indian Ocean, on an island called Madagascar, there were Polynesians. And in 1992 a study of genetics found that a tribe of native Americans in Southeast Alaska called the Haida have a Polynesian genetic makeup; their traditions say that they came from islands to the South.

How did these oceanic people explore so many miles of open ocean? How did they build their canoes? How did they sail over such long distances--2500 miles--without instruments?

There have been different theories about how Polynesia was settled. In 1946, Thor Heyerdahl sailed a balsa log raft from South America to the Tuamotus. He believed that the Polynesians did not have the ability to sail against the easterly wind and current, so they must have rode the wind and current west from South America. This went against our oral traditions, which tell of great navigators and voyagers, and against the archaeological, linguistic, genetic, and botanical evidence that points to islands off Southeast Asia as the original homeland of the Polynesians. Others, like Andrew Sharp, agreed that the Polynesians came out of Asia, not South America, but that they did not have the skill to navigate more than 100 miles from land, but were blown off course by storms and drifted to new islands. So the perception in the past was not very flattering to those of us of Polynesian ancestry.

1973

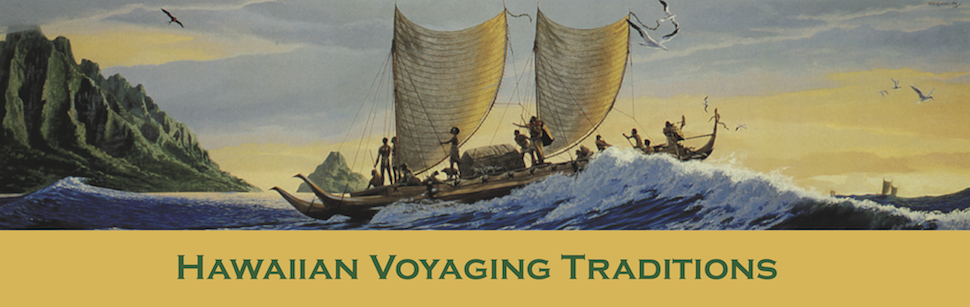

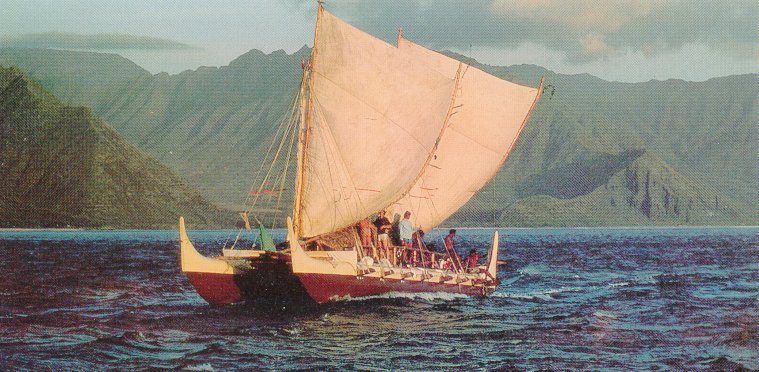

The Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) was established in 1973 by an anthropologist from California, Dr. Ben Finney; a Hawaiian artist, Herb Kawainui Kane; and a writer who loved the sea, Tommy Holmes. They wanted to show that the ancient Polynesians could have purposefully settled the Polynesian Triangle in double-hulled voyaging canoes, navigating by the sun, stars, swells, seabirds, and directional clues in nature. The only way to do this was to get out of the four walls of the academic world, build a voyaging canoe, and sail it to Tahiti. On March 8, 1975, over 24 years ago, Hokule'a was launched from the sacred beach of Hakipu'u and Kualoa on the windward coast of O'ahu.

Back in the early seventies, before Hokule'a was even built, when PVS was putting the dream together, they said, "We need to get a Polynesian navigator." The only traditional navigator known to be left on earth was a man by the name of Tevake. He came from a small island-a Polynesian outlier in Melanesia. A group from Hawai'i went down to his island to talk to him to see if he could navigate a canoe that wasn't even built. They explained the project and all Tevake said was "We'll see." Six months after that trip, the group received a letter from Tevake's daughter informing them that Tevake had got up one day, said good-bye to his whole family, went to sea in his canoe, and never came back. As in the old way, he chose his life in the ocean and it was there that he chose his death.

Back in Hawai'i, we were faced with the extinction of our voyaging traditions. There was no navigator from our culture left. Then there came a very special man. Without him, our voyaging would never have taken place. His name is Mau Piailug and he is from a small island called Satawal in Micronesia. He navigated Hokule'a on her first voyage in 1976.

1976

On May 1 Hokule'a left Hawai'i on a voyage to Tahiti, to retrace this traditional migratory route.

Thirty-three days after she left Maui, Hokule'a entered Pape'ete Harbor in Tahiti. Seventeen thousand people came down to greet the canoe-over half the population of the island. When the canoe got to the black sand beach, so many children climbed onto the back of the canoe that its stern sank. People couldn't see past the crowd, so they climbed into the trees. What had begun as a scientific experiment to prove a theory about the settlement of Polynesia, had touched a deep root of cultural pride in Polynesian people. It was a spontaneous reaction on the part of these people who had maintained their language and genealogies, and who knew the names of their great navigators and great voyaging canoes, but who no longer had a canoe. So when Hokule'a entered the bay she was a powerful symbol that reminded them of the greatness of their culture and their heritage and therefore themselves.

After the voyage Mau, returned to Micronesia, and with him went the knowledge of the traditional art of wayfinding. But Mau had ignited a strong interest in many members of the Voyaging Society to continue sailing and learning about navigation. We couldn't just talk or read about our culture in order to revive it-we had to live it, to practice it. Those who sailed down to Tahiti and back said we needed to continue, we needed to nurture and revive our voyaging traditions.

1978

In 1978 in response to this interest, Hokule'a again left for Tahiti. Six hours into the voyage, in the middle of the night, Hokule'a capsized between O'ahu and Lana'i. In an heroic effort, Eddie Aikau, one of Hawai'i's most experienced ocean men left on a surf board to get help for his fellow crew members. He was never seen again.

Eddie's loss was a painful experience, but it raised the standards of preparation and safety to a new level; since 1978 not a single crew member has been lost at sea.

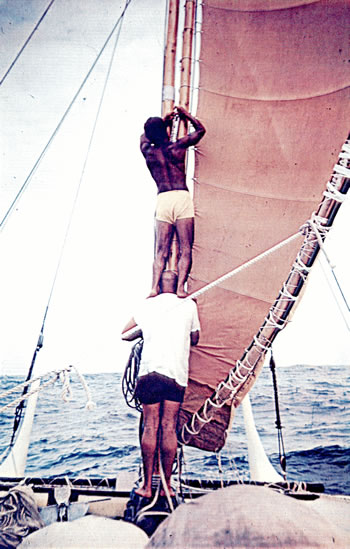

After 1978, recognizing that it was unprepared to conduct a long voyage, PVS turned to Mau and asked him to teach them about sailing and navigation. Mau agreed, and for the next two years he helped prepare the members of the Voyaging Society for the enormous task of sailing and navigating a deep sea voyage. Mau Piailug had returned to Hawai‘i as our teacher instead of our navigator. The great genius of Mau Pialug is that he could cross great cultural bridges and help us - like children taken by the hand- find our way on the sea. All of this came from a very powerful sense of caring on his part.

1980

In 1980, we sailed to Tahiti and back. The difference on this trip was that the canoe was navigated, captained, and crewed by people from Hawai'i.

1985-1987

After we got back from Tahiti, we started thinking about what to do and where would it be important to go to? Other parts of Polynesia have great canoe traditions. We wanted to take Hokule'a to these different places and meet these people. From 1985-1987, we sailed from Hawai'i down to Tahiti, through the Cook Islands, down to Aotearoa, up to Tonga and Samoa, and then against the trade winds to the Cook Islands and back to Tahiti (the route which Heyerdahl said couldn't be done), up to the Rangiroa and back to Hawai'i. A voyage of 16,000 nautical miles. It was driven by this notion that reviving our culture is important to our people.

And this, like the other voyages, was created out of dreams. The dream was to go to this place called Aotearoa ... "Land of the Long White Cloud." We started two years before the voyage, just in the planning and the preparation. To cross 1,700 miles from Raratonga to Aotearoa, even though it's shorter than the trip from Hawai'i to Tahiti, was very difficult. We left the tropics and went into the subtropics. We went into different weather systems, much more complicated weather systems than the ones we were accustomed to.

When we arrived there, we were invited to this special occasion at the marae at Waitangi. We learned that the marae houses the ancestral spirits of the Maori people as well as the living. We watched grandchildren and grandparents dance together and sing together. We were greeted in the traditional way because that was the way it's supposed to be done. We understood that in these houses were not just people, but their genealogies. They trace their ancestry back to the canoes that brought them to Aotearoa. That is very powerful. The marae houses not just their past and present, but their future. And because they are connected to the past, it's much easier for them to see what kind of future they want to voyage to. This was another part of our work toward renewal.

Sir James Hinare got up and spoke. He told us that we had proven that it could be done, that his ancestors had traveled great distances in voyaging canoes to settle Aotearoa. This was a very special moment for him, a very special occasion, and he laughed and he cried. We recognized from him that we come from a powerful heritage and ancestry. The voyaging canoe is just one instrument to connect to that heritage. Sir James Hinare also made an incredible statement: because the five tribes of Taitokerao trace their ancestry and their family from the names of the canoes, and because the people of Hawai'i came by canoe, therefore by our traditions, we must be the sixth tribe of Taitokerao.

1990-1993

In recognition of the impact of voyaging on the revival of Hawaiian culture, the Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program, an organization working to strengthen the Hawaiian community based on its common history and heritage, contracted PVS to construct a double-hulled, voyaging canoe made entirely of natural materials. A 9-month search of the Island of Hawai'i's koa forests resulted in nothing-not a single koa tree large enough or healthy enough for the hulls of a voyaging canoe was found. The ancient Hawaiians built hundreds of voyaging canoes from koa trees, but in 1990, given the decline of Hawai's native forests, we were unable to build even one.

This taught the Voyaging Society a powerful lesson: the health of our culture is strongly tied to the health of our environment. Fortunately for the project, there was another historical source of wood for canoes-drift logs from the Pacific Northwest. In an extraordinary act of kindness, the native people of Southeast Alaska gave two, 400-year old, spruce logs to the Society to build a voyaging canoe. The effort brought together community groups, organizations, and countless individuals who contributed more than 500,000 hours to build and sail the canoe. The canoe, named Hawai'iloa, was completed under the leadership of Wright Bowman, Jr.

Launched in 1993, Hawai'iloa, represented a new level of community involvement in voyaging, a new appreciation for Hawai'i's environment, and the start of a deep friendship with the native peoples of Southeast Alaska.

1992

Pacific island nations come together every four years to celebrate their visual and performing arts. In 1992, the festival was to be held in Rarotonga. The Prime Minister of Rarotonga said, "Let's dedicate the festival to our historic voyaging ancestors," and he asked that each island group bring a model of its canoe to display. And somebody said, "No, we will sail our canoes." And you know Polynesians how they are! That challenged everyone else. So they decided to build canoes. New canoes were being built in Aotearoa, Rarotonga and Tahiti.

They called Hawai'i and asked for assistance and it was a great opportunity for us to repay - in a small way - the kindness we found all through the South Pacific. They had taken care of Hokule'a as if it was their own canoe. It also gave us the opportunity to move into a new area - education. We recognized the importance of education in the revival of our culture. So Hokule'a voyaged to Rarotonga that year to join the celebration. She was one of seventeen canoes that participated in the festival. We asked that each canoe bring a stone from its home island. It was the beginning of a sharing of knowledge that is Pacific-wide.

Spring 1995

The voyage to the Marquesas and back in 1995 was not just about Hokule'a, but about the children of Hokule'a - the newly built Hawaiian canoes Hawai'iloa and Makali'i; Te 'Au O Tonga and Takitumu from Rarotonga; and Te 'Aurere from Aotearoa. We all went to a place called Taputapuatea in Ra'iatea, formerly the cultural center of Polynesia, where navigation and genealogy were taught. This was perhaps the most appropriate place to start the voyage that would take these canoes to the Marquesas and on to Hawai'i.

We trained navigators for five years. Recognizing that for our culture to be strong, if navigators are an important part of that, then we have to build strength in numbers. Six canoes made the voyage from the Marquesas to Hawai'i, over 2,200 miles of open ocean. Five were guided by navigators from their own islands, trained to navigate in the ancient way. We staggered the departures from the Marquesas, so that each canoe was by itself. If we were all together, one canoe would be leading, and everybody else would be following. So each canoe sailed on its own and they all made landfall in Hawai'i. The navigation training worked. But what's more interesting is that the voyage showed that the process of education can work to accelerate learning when you combine tradition and science, and when you have people who are motivated -- compassionate enough to work hard and commit themselves to a difficult task as this is.

Both the 1992 and 1995 voyages emphasized education, an important tool essential to sharing the experiences and values of voyaging with a larger audience. In addition to training new navigators and voyagers, PVS reached out to thousands of school children in the Department of Education through a long-distance education program. During the voyage students tracked the canoe on nautical charts, learned about their Pacific world, and used the canoe and its limited supply of food, water, and space, to explore issues of survival, sustainability, and teamwork. On the 1992 return voyage PVS educational programs reached as far as the Space Shuttle, as Shuttle crew member Lacy Veach, a Hawai'i native, participated in conversations about sustainability and exploration with the canoe and Hawai'i classrooms. In addition to these programs, PVS also began navigation and sailing courses at the University of Hawai'i and Windward Community College.

Summer 1995

Within days of arriving in Hawai'i after the 1995 voyage, Hokule'a and Hawai'iloa were shipped to Seattle. Hokule'a sailed south along the West Coast, reaching thousands of people who no longer lived in Hawai'i, but longed to share in the canoe's legacy. Hawai'iloa sailed north to thank the native peoples of Southeast Alaska for their gift of spruce trees. This was an opportunity for PVS to give back to them, but at each stop the canoe and crew were overwhelmed with gifts and kindness. These native people were responding to the fact that, like them, the Hawaiians were working to recover their native traditions.

This Northwest Voyage taught PVS a great deal about another culture's efforts to renew its traditions, and about their determination to care for natural resources, in order to build a healthy future for their people.

Renewal of Pride in Culture and Heritage

In the wake of her accomplishments, Hokule'a has helped to renew the pride that Hawaiian people have for their culture and heritage. In turn this has made a contribution to raising the self-esteem of Hawaiian people.

Recognizing that self-esteem and health are inextricably linked, a cooperative effort emerged in 1996 between The Queen's Health Systems and the Polynesian Voyaging Society. It was called Malama Hawai'i – "Caring for Hawai'i." Native Hawaiians have the worst health and socioeconomic indicators of any ethnic group in Hawai'i, and for years Queen's was been working to improve these statistics. Malama Hawai'i's first project was the 1996-97 Statewide Sail, a 10-month, 2,000 mile journey, in which more than 25,000 school children and community members visited or sailed on Hokule'a. The Sail was an effort to "connect" with Hawaiian communities, in order to find ways to support efforts to improve their health. What Malama Hawai'i found was cultural renewal taking place within these communities. Every community that Hokule'a visited celebrated its strengths with pride, and did not define itself by negative statistics. The Statewide Sail helped Malama Hawai'i to understand that the lives of the next generation of Hawaiians are already being shaped by this spirit of cultural renewal, and because of it we believe that in the future they will not be burdened with the same negative health and socio-economic statistics of the past.

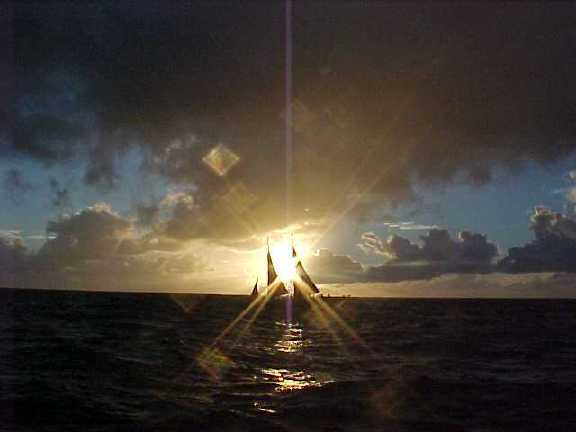

What began in 1973 as a scientific experiment to build a replica of a traditional voyaging canoe for a one-time sail to Tahiti, became an important catalyst for a generation of cultural renewal and a symbol of the richness of Hawaiian culture and of a seafaring heritage which links together all of the peoples of Polynesia. No one could have imagined that by the end of the century, Hokule'a would have sailed more than 100,000 miles reaching every corner in the Polynesian Triangle, and the West Coast of the United States. [In 1999, Hokule‘a voyaged to the island of Rapanui, in the far southeastern corner of the Polynesian Triangle.]

In 1973 there were no Polynesian voyaging canoes; today there are six with others under construction. In 1973 there was only one deep-sea navigator that PVS knew of; today there are nine, with several more in training, along with 135 experienced deep-sea sailors in Hawai'i alone-ensuring that the Hawaiian people will never again lose their traditions of voyaging and navigation. Over the last 25 years, the family of the voyaging canoe has grown to more than 525,000 men, women and children who have participated in PVS programs of education, training, research and dialogue.

The voyaging revival, through Hokule'a and her children, is what the 25th Anniversary Celebration of Hokule'a will be about. March 6, 2000 will mark 25 years since Hokule'a was launched at Kualoa. We will gather again at Kualoa to honor the kupuna, teachers, and many others who contributed to her achievements.