No Nā Mamo, For the Children: 1992 Voyage for Education

Dennis Kawaharada

The 1992 Voyage to Ra'iatea and Rarotonga, called No Nā Mamo, For the Children, was designed to train a new generation of voyagers to sail Hokule'a, to share the knowledge and values of voyaging with students in Hawai'i and to celebrate the revival of canoe building and traditional navigation throughout the Pacific with visit to Tahiti and the Sixth Pacific Arts Festival, held that year in Rarotonga.

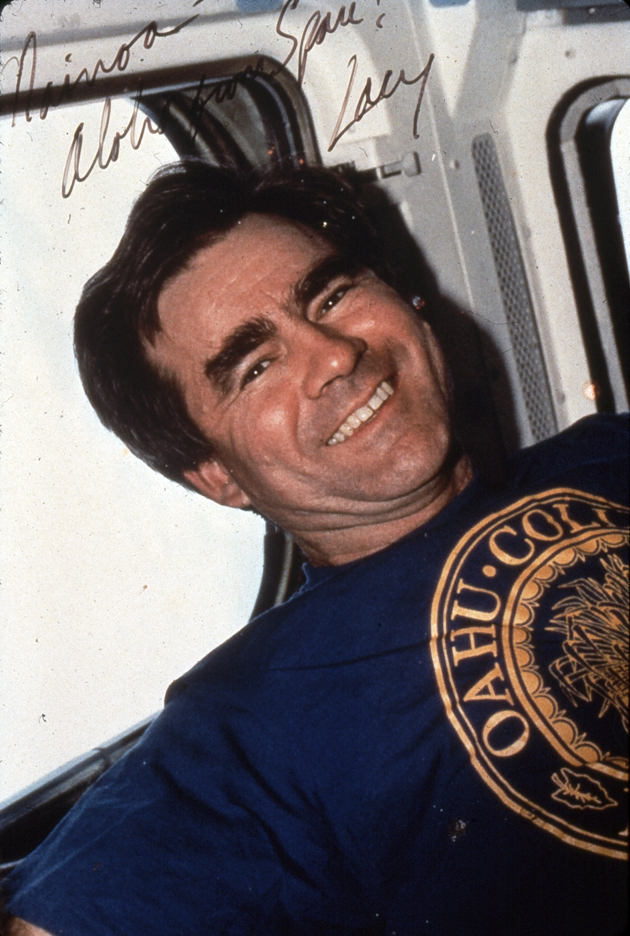

On each of the four legs of the voyage, Hokule'a had new navigators to guide her. In addition to training new navigators and crew members, PVS reached out to thousands of school children in Hawai'i through a long-distance education program. During the voyage students tracked the canoe on nautical charts, learned about their Pacific world, and used the canoe and its limited supply of food, water, and space, to explore issues of survival, sustainability, and teamwork. On the voyage back to Hawai'i, the crew of the canoe contacted the crew of the Space Shuttle Columbia flying overhead and shuttle crew member Lacy Veach, a Hawai'i native. The two vessels participated in conversations with students in Hawai'i about the importance of exploration.

The following fifty vignettes about the voyage were broadcast on KCCN Radio, from February to April 1993.

Hawai‘i to Tahiti (June 17-July 15, 1992)

1. No Na Mamo / For the Children

2. The Searoad to Tahiti

3. Honaunau

4. Departure

5. In the Northeast Tradewinds

6. The Zone of Converging Tradewinds

7. Southerly Winds

8. Seabirds

9. Landfall: the Tuamotus

10. Ancient Voyagers between Hawai'i and the Society Islands

Hawai‘i to Tahiti Crew Members: Nainoa Thompson, Sailmaster; Chad Baybayan, Co-navigator; Shorty Bertelmann, Co-navigator; Clay Bertelmann, Captain; Nailima Ahuna, Fisherman; Dennis Chun, Historian; Maulili Dixon, Cook; Kainoa Lee; Liloa Long; Jay Paikai; Chad Paison; Ben Tamura, M.D.; Tava Taupu.

Voyagers – Ancient and Modern

11. Kapena Clay Bertelmann

12. Navigator Chad Baybayan

13. Navigator Shorty Bertelmann

14. Ho'okele-wa'a: The Traditional Navigator

15. The Wind Gourd of La'amaomao

The Art of Wayfinding

16. Course Strategy

17. Holding Direction

18. Houses of the Horizon

19. Dead Reckoning

20. Anticipating Wind and Weather

At Sea

21. Dangers at Sea: The Legend of Raka

22. Dangers at Sea: Hokule'a

23. Provisioning the Canoe

24. Fishing on Hokule'a

Sailing in Tahiti (Sept. 1-Sept. 19, 1992)

25. Tautira, Tahiti (Sept. 1)

26. A Day of Rest: Sunday-Tautira

27. Sail from Tautira, Tahiti, to Fare, Huahine (Sept. 10-11)

28. Huahine: Dr. Sinoto and Archeology

29. Ra'iatea: The Heart of Central Polynesia

30. Taputapuatea: The Legacy of 'Oro

31. Taputapuatea: The Break-Up of the Friendly Alliance

32. Taputapuatea: The Lifting of the Kapu (1985)

33. Taputapuatea: Reconciliations (Sept. 16)

34. Taputapuatea: The Drum and the Hula

35. Taputapuatea: A Meeting of Navigators (Sept. 17)

36. Kapena Billy Richards

Tautira - Huahine Crew Members: Nainoa Thompson, Sailmaster; Chad Baybayan, Navigator; Keahi Omai, Navigator; Billy Richards, Captain; Gilbert Ane; John Eddy, Film Documentation; Tiger Espera; Brickwood Galuteria, Communications; Harry Ho; Sol Kahoohalahala; Dennis Kawaharada, Communications; Reggie Keaunui; Keone Nunes, Oral Historian; Eric Martinson; Nalani Minton, Traditional Medicine; Esther Mookini, Hawaiian Language; Mel Paoa; Cliff Watson, Film Documentation; Nathan Wong, M.D.

Sailing in the Cook Islands (Sept. 20-Oct. 25, 1992)

37. Landing at Mauke (Sept. 23)

38. Aitutaki (Sept. 25)

39. Rarotonga and Tangiia, the Voyager

40. Sails to Rarotonga: Pacific Arts Festival (Oct. 15-Oct. 22)

41. The Pageant of Vaka: Pacific Arts Festival (Oct. 21)

42. Kapena Gordon Pi'ianai'a

Borabora to Rarotonga Crew Members: Nainoa Thompson, Sailmaster; Chad Baybayan, Navigator; Gordon Pi`ianai`a, Captain; Moana Doi, Photo-documentator; John Eddy, Film Documentation; Ben Finney, Scholar; Wally Froseith, Watch Captain; Brickwood Galuteria, Communications; Harry Ho; Ka`au McKenney; Keahi Omai; Keone Nunes, Oral Historian; Billy Richards, Watch Captain; Cliff Watson, Film Documentation; Cook Islands Crew Members: Clive Baxter (Aitutaki); Tura Koronui (Atiu); Dorn Marsters (Aitutaki);Tua Pittman (Rarotonga); Nga Pou`a`o (Mitiaro); Ma`ara Tearaua (Mangaia); Pe`ia Tua`ati (Mauke).

The Voyage Home (Oct. 26-Dec. 12, 1992)

43. East to Tahiti (Oct. 26-Nov. 1)

44. Conversation with the Space Shuttle (Oct. 28)

45. Kapena Mike Tongg

46. Landfall: Hawai'i (Nov. 30-Dec. 1)

47. Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld

48. Navigator Kimo Lyman

49. Welcome Home Ceremonies (Dec. 5)

50. Hawaiiloa and the Marquesas-1995

Rarotongato Hawai‘i Crew Members: Sailmater Nainoa Thompson; Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld; Navigator Kimo Lyman; Kapena Mike Tongg; Watch Captain Abraham Ah Hee; Watch Captain Aaron Young (Medical Officer); Carlos Andrade (Hawaiian Language); Terry Hee (Designated Fisherman); Archie Kalepa; Suzette Smith; Scott Sullivan (Communications); Wallace Wong; Gary Yuen (Cook)

Hawai‘i to Tahiti (June 17-July 15, 1992)

1. No Na Mamo / For the Children: The 1992 Voyage of the Hokule'a

Riding the winds like a seabird and setting its heading by the stars and ocean swells, Hokule'a made its fourth voyage to the South Pacific and back in 1992. Twelve years ago, on Hokule'a's second voyage in 1980, Nainoa Thompson became the first Hawaiian and the first Polynesian since the 14th century to sail long ocean distances without modern navigational instruments. Now Thompson wanted to train a new generation of voyagers and to pass on the knowledge of wayfinding he had acquired from Mau Piailug, a master navigator from Micronesia, who had guided Hokule'a on its first voyage to Tahiti in 1976.

During the 1992 voyage Thompson was mentor to six new Hawaiian navigators and trained twenty-four new crew members. The voyage was an opportunity for the crew not just to learn sailing and wayfinding, but to relive the travels of the ancients and to visit or revisit the ancestral homelands and distant relatives in the Society and Cook Islands. Schoolchildren in Hawai'i also participated in the voyage through live daily reports from the canoe; and in the classroom, they learned about the pride and achievements of Polynesian voyaging.

Because of its focus on training and education to perpetuate voyaging for future generations, the 1992 voyage was called "No Na Mamo, For the Children."

The voyage also contributed to the revival of voyaging throughout the Pacific. Tahitians, Cook Islanders, Maoris and other islanders joined the Hawaiians in building and sailing canoes. A meeting of Polyneisan navigators on the island of Ra'iatea in September was the first in over 500 years; and a pageant of Pacific canoes in Rarotonga in October celebrated the seafaring heritage of the Pacific Islands as part of the sixth Pacific Arts Festival.

"No Na Mamo" represented a tremendous effort in cultural education and revival that, like the ancient voyagers, reached out across the Pacific.

2. The Searoad to Tahiti

The route between Hawai'i and Tahiti is the longest one traveled by Hokule'a-over 2,250 miles each way. The sail to Tahiti is a challenge because the canoe must go 300 miles east against the prevailing tradewinds and the west-flowing equatorial currents in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

Oral traditions indicate that two-way voyages were made between Hawai'i and the Society Islands during the 12th to 14th centuries by such voyagers as the ali'i Mo'ikeha and the kahuna Pa'ao. Some Western scholars had doubted that such voyages could have been made in Polynesian canoes without Western navigation instruments. To convince these skeptics that such voyages were possible, Dr. Ben Finney, Tommy Holmes, and Herb Kawainui Kane formed the Polynesian Voyaging Society in 1975 to build and sail Hokule'a. Since then, Hokule'a has completed the two-way voyage to the south Pacific four times.

To get to Tahiti, the canoe heads over 700 miles in the northeast trade winds in the direction where the bottom star in Hanai-a-ka-malama, or the Southern Cross, rises from the horizon. Then the canoe makes its way slowly through unfavorable sailing conditions in the zone of converging tradewinds, where it encounters heavy cloud cover, frequent squalls, and light winds and calms called doldrums. About 200 miles north of the equator the canoe reaches the southeast trade winds, which carry it swiftly south toward Tahiti, still over 1100 miles away.

Without the exact measurements of Western instruments, the wayfinder cannot pinpoint the island of Tahiti as a destination. Rather, he targets a 400-mile wide screen of islands around Tahiti, from Maupiti in the western Society Islands to Manihi in the western Tuamotus. Once the wayfinder sights and identifies an island in this screen, he knows the direction of Tahiti and guides the canoe to its destination.

3. Honaunau

Sailmaster Nainoa Thompson planned for Hokule'a to depart for Tahiti in early June so the canoe could sail out of the hurricane zone in the northern hemisphere before the hurricane season, which begins in late June.

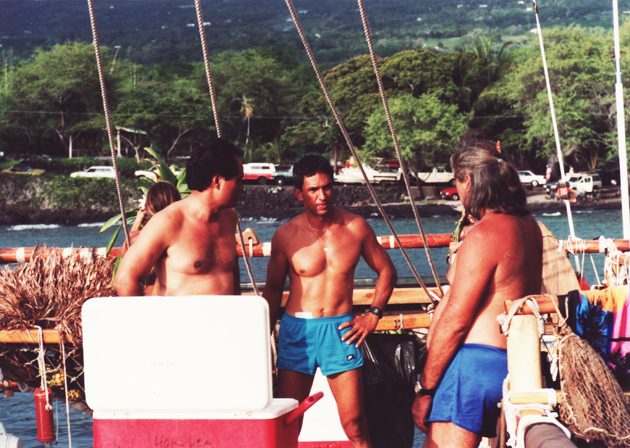

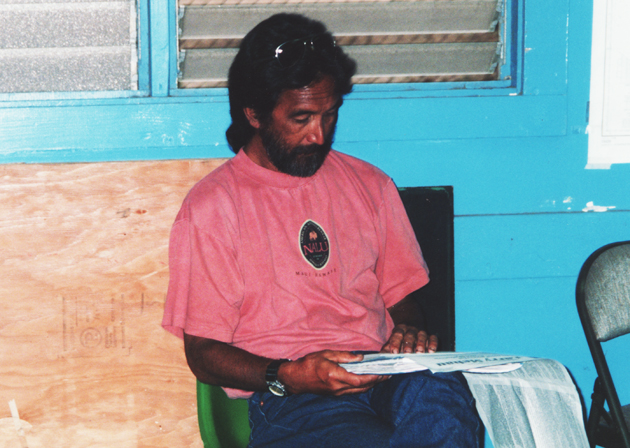

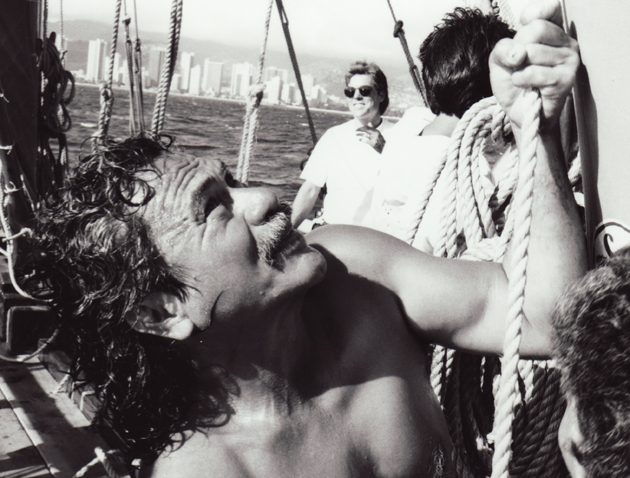

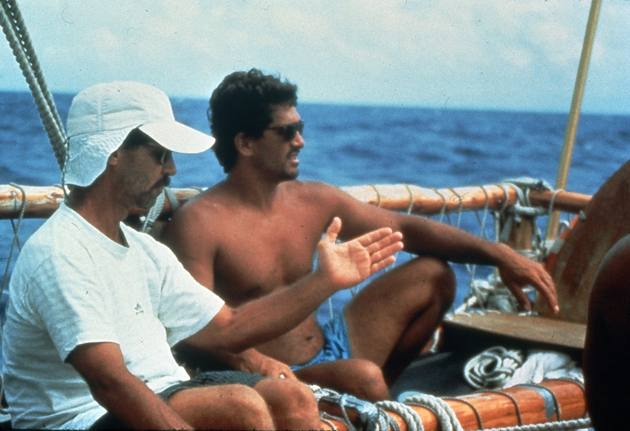

Nainoa talking with Captain Clay Bertelmann before departure.

Also, by leaving in early June, the wayfinders would have a moon in mid-June when the canoe reached the zone of converging tradewinds, where heavy cloud cover and confused seas make non-instrument navigation difficult, especially at night. The moon can be used a guide on cloudy nights, and its light on the ocean swells make them easier to see and read for direction.

After a spirited run from Honolulu with an apprentice crew under veteran crew members led by Captain Gordon Pi'ianai'a, Hokule'a arrived in Honaunau on June 13. During the year before the voyage, the canoe had been refitted and relashed under the direction of Alan Paquin and Gil Ane and was ready for its sail to Tahiti.

Honaunau was an ideal departure point from a practical point of view. Water and supplies can be loaded easily. It is also near Ka Lae, or South Point, the closest land in the Hawaiian Islands to Tahiti. The canoe planned to sail down the coast of Kona and Ka'u, then swing out at South Point into the northeast trade winds on a SSE course toward Tahiti.

Honaunau was also the place chosen for spiritual preparations for the voyage. On June 14 at Pu'uhonua o Honaunau National Park, an 'awa ceremony was conducted by Sam Kaai and Hale Makua, with the assistance of members of Na Koa, or The Warriors, and Kalai-wa'a, or The Canoe Builders, to initiate new crew members into the Hokule'a family and to prepare the crew spiritually for departure. Kaai welcomed and blessed the crew, saying, "These are the children of the living breath...They go out to the deep ocean to find out what the original song was...We're not lost. We're going home."

4. Departure

Each morning before the departure of Hokule'a from Honaunau, wayfinder Shorty Bertelmann, sometimes with his teacher Mau Piailug, went to Ka Lae, or South Point, to observe the horizon and clouds at sunrise for weather signs indicating the right wind to speed the canoe on its way.

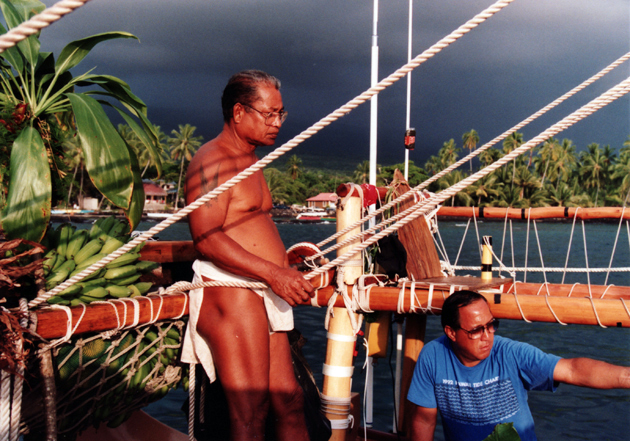

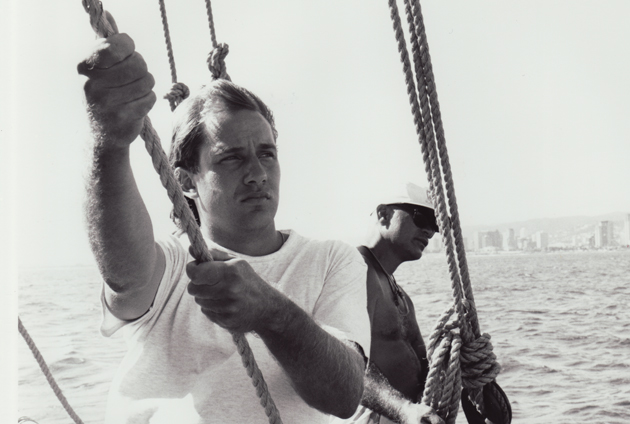

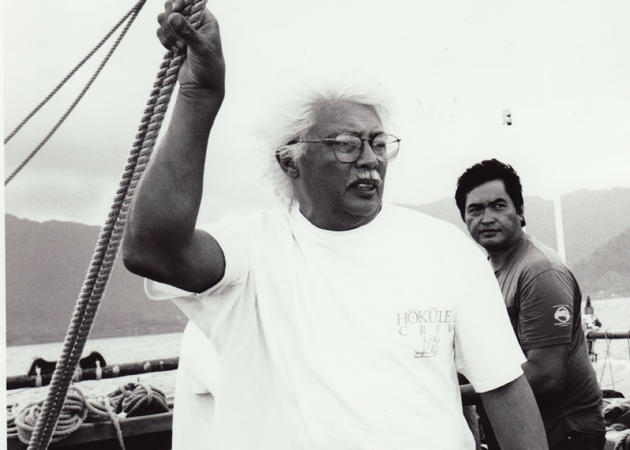

Mau and Harry Ho, Honaunau, 1992

The wayfinder looks for "smoke" at the horizon-the salty spray that wind whips off the surface of the sea; the more smoke, the stronger the wind. He watches the movement of clouds and the size and direction of the ocean swells to determine the strength and direction of the winds. He observes how far apart the largest swells are; the farther apart the swells, the farther the wind generating them. He notes the types of clouds and the color of the sky for clues to weather. He compares each day's weather with the weather on previous days to discern a pattern.

Hokule'a's wayfinders wanted a northeasterly rather than an easterly wind for departure, so that the canoe could gain some easterly direction as soon as it rounded Ka Lae. On the morning of June 16, the wind was right-gusting up to 35 knots and holding a northeasterly direction. At 1 a.m. in the morning of June 17, Hokule'a was towed out of Honaunau by the fishing boat Sammy Lu. Outside the wind shadow of the Big Island, the tow line was dropped and the canoe headed south along the coast of Kona and Ka'u to begin its 2,250 mile journey to Tahiti.

The canoe was guided by wayfinders Chad Baybayan and Shorty Bertelmann; the captain was Clay Bertelmann. The sailmaster, responsible for the sail plan and sail trim, was Nainoa Thompson. Nine crew members joined them, a total of thirteen.

To observers who had gone out to Ka Lae to see the canoe off, Hokule'a, even through binoculars, looked very small against the vast blue expanse of sea and sky brightened by the morning sun.

5. In the Northeast Tradewinds

After leaving Honaunau on June 17, Hokule'a sailed south southeast for five days in strong tradewinds, with 8-10 foot seas breaking onto the canoe. It was a wet, wild ride. The canoe averaged about 144 miles per day, and made good about 700 miles, down to around 9 degrees N latitude, the northern edge of the area where the northeast tradewinds give out and thick cloud cover, squally weather, and doldrum conditions are usually encountered.

In normal 15-25 knot tradewinds, the sixty-two foot Hokule'a, rigged with two sails, travels at an average speed of four to six knots, or about four-and-a-half to seven miles per hour. At this speed the canoe covers 100-150 nautical miles per day. It can go over ten knots and over 200 miles a day in stronger winds with a following sea that allows the canoe to surf along on the wind-generated swells.

Built in 1975, Hokule'a was the first double-hulled voyaging canoe to sail in Hawaiian waters in hundreds of years. Since Hawaiians had ceased long-distance voyaging long ago, no examples of voyaging canoes were available as models for the new canoe. Hawaiian artist Herb Kane based the design of Hokule'a on drawings of canoes made by artists employed by Captain Cook and other early explorers of the Pacific; Hokule'a has been modified since then with advice from expert sailing vessel designers like Rudy Choy.

Although the Polynesian Voyaging Society wanted to use traditional materials and tools in building the canoe, the construction would have been too time-consuming as the builders relearned the ancient arts of canoe-building. Thus, the hulls were made from plywood strengthened by fiberglass and resin; the sails were made from canvas rather than lauhala; and the lashings were done with synthetic cordage rather than sennit.

6. The Zone of Converging Tradewinds

Six days after Hokule'a left Honaunau for Tahiti, the crew began experiencing the first signs of the zone of converging tradewinds-a slackening of the winds and an increase in clouds.

The zone of converging tradewinds is the region just north of the equator where the NE and SE tradewinds meet and push hot, humid equatorial air upward into massive, towering clouds. From 200 to 400 miles wide north to south, it is the cloudiest region on earth. It is also noted for its sudden squalls. The heavy cloud cover obscures the stars and sun, making navigation by celestial bodies difficult; the frequent squalls, with their shifting winds, force the canoe to tack, or change directions, making sailing and keeping track of progress difficult.

South of the region of heavy clouds and squalls, voyagers encounter light winds and doldrum conditions.

The days of sudden squalls and windless calm test the concentration of the wayfinder and the patience of the crew, but for sailmaster Nainoa Thompson, the zone of converging tradewinds has a unique beauty; its extreme, unpredictable weather is like no other weather on earth. On days when sunlight is diffused in the heavy cloud cover, the sea mirrors the light and turns golden; on clear nights, the sea surface can be so smooth that the stars and constellations are reflected in it; on nights of 100 percent cloud cover, the ocean and sky are pitch black. Sudden squalls can bring wind, rains, thunder, and bolts of lightning, which explode on impact with the water. From dead calms, to sudden squalls with gale force winds; from cloudless days and nights to days and nights of total cloud cover and total darkness-the weather challenges the voyagers' sailing skills and resolve.

(Sources: Interviews with Bernie Kolinsky and Nainoa Thompson)

7. Southerly Winds

The sailing strategy in the fickle weather of the converging tradewinds zone is to try to get out of it as quickly as possible by sailing as directly as possible across the zone. While some have suggested Hokule'a's crew paddle through the doldrums, it has never done so because paddling would require too much energy, and crew members would begin to consume too much of the limited water and food supply. Instead, the crew patiently sails the canoe south in the light and shifting winds.

In 1992, the canoe spent thirteen days in the 300 mile wide zone of converging tradewinds, bedeviled by squalls and shifting winds with a persistent southerly component. Navigator Chad Baybayan reported that the crew had to tack, or change directions, up to five times in one day. With southerly winds preventing the canoe from heading south, the wayfinders were forced to choose between going east or going west. They did not want to go west because of the danger of getting downwind of Tahiti and being forced to sail against the wind to get to the island. So the canoe sailed east, farther east than it has ever gone before.

On July 7, when the canoe finally left the zone of converging tradewinds, the wayfinders had to rethink their position. An east-flowing current runs through the zone. The canoe had spent five more days in the zone than had been originally anticipated-so how far east had the canoe actually gone? On July 8, the wayfinders decided that they had been too conservative in their estimates of easterly direction travelled and that the current had carried canoe farther east than they had allowed for in the sail plan; so they revised their estimated position, adding about 180 miles of easting. On that day, a satellite report placed them about 110 miles east of their previous estimate.

8. Seabirds

While sailing south in the zone of converging tradewinds, Hokule'a's crew reported an 'a, or booby bird, was making itself at home on the canoe. In jest, the crew nicknamed the bird "Dinner." In fact, these torpedo-shaped birds, which dive for fish and follow vessels at sea, were eaten by Polynesians and European sailors on long ocean voyages. Apparently dim-witted, these prehistoric birds can be captured by hand.

The 'a is just one of the types of seabirds Pacific voyagers encounter. Sooty terns, wide-winged albatrosses, tropic-birds with long tail feathers, and low-flying petrels and shearwaters are pelagic-that is, they spend much of their lives roaming the ocean in search of food or migrating great distances across the Pacific. They return to land once a year to nest. Other birds, like the 'a and the 'iwa, or frigate birds, are land-based, but are capable of staying out at sea for long periods, the 'iwa, with its distinctive kinked wing and V-shaped tail, by floating on the wind; and the 'a by resting on floating debris, buoys, vessels, or even the backs of turtles, where they have been observed sleeping.

Two special birds-the noio, or noddy tern, and the manu-o-Ku, or fairy tern-aid Hokule'a's wayfinders in landfinding. The flight of these land-based birds indicates the way to land because they fly out from land in the morning to fish, and return to land in the afternoon or evening. The noio, dark brown or black, with a white cap and sharp beak, ranges about 40 miles from its home island; the manu-o-Ku, pure white, with black eyes, ranges farther, up to about 120 miles from its home island. When the wayfinders are looking for land, they watch for these birds in the morning and afternoon to estimate how far and in which direction an island might be.

(Source: Craig S. Harrison, Seabirds of Hawaii)

9. Landfall: the Tuamotus

Hokule'a found the southeast tradewinds on July 8 and picked up speed on its southerly course, making good between 120-200 miles a day. As it approached the latitude of the Tuamotu Archipelago, captain Clay Bertelmann posted a forward watch to look for land.

The Tuamotous are a chain of 78 coral atolls stretching over 1200 miles from east to west. They were nicknamed "The Dangerous Isles" by early European explorers of the Pacific because ships ran aground on the sunken reefs of the hard-to-see atolls. The highest points on these atolls are the tops of coconut trees-about 60 feet in height. The tree tops can be seen from the deck of the canoe as a thin scratch on the horizon from seven to eight miles away; or from ten miles away if the observer climbs the mast.

But land can be detected by a wayfinder before it is actually sighted. The first sign may be land-based birds like the manu-o-Ku, or fairy tern, and the noio, or noddy tern. Swells from the direction of an island wrap around an island so the pattern of swells changes. Swells going towards the island bounce off the island back toward the canoe. If the island is upwind, human, animal, or plant smells and drifting land vegetation may reach the canoe. Other clues include special cloud shapes over islands; a green blush on the bottom of clouds above the islands in the daytime; or a glow above an island created by sunlight or moonlight reflecting up from the white sand and smooth water of a lagoon. Underwater lightning may also point the way to land.

On July 13, the Hokule'a crew sighted and identified Mataiva, the westernmost island in the Tuamotus. From this sighting, they knew that Tahiti was about 170 miles to the south southwest. With native-born Marquesan Tava Taupu taking over navigation, the canoe found Tahiti and landed at Papeete on July 15. The voyage from Hawai'i had taken 29 days.

(Source: Lewis, We, the Navigators)

10. Ancient Voyagers between Hawai'i and the Society Islands

Hokule'a's fourth voyage, like its first three voyages, was a re-creation of two-way travel between Hawai'i and the Society Islands during the 12th to 14th centuries. These ancient voyagers sailed for many reasons, sometimes for exploration or adventure, at other times out of necessity.

The voyager Mo'ikeha and his brother 'Olopana are said to have returned to their ancestral homeland of Tahiti after a flood destroyed their lands in Waipi'o, Hawai'i. Mo'ikeha came back to Hawai'i after an unhappy affair with his brother's wife, or because his brother was jealous of his growing wealth. After settling in Kaua'i, Moikeha taught his son Kila navigation and Kila sailed to Tahiti and brought back another of Moikeha's sons, La'a, the Sacred One. Eventually, the two sons of Mo'ikeha took their father's bones back to Tahiti for burial. Later, Kaha'i, a grandson of Mo'ikeha, is credited with introducing ulu, or breadfruit, to Hawai'i.

Voyaging benefitted the Polynesians by expanding the resources and options for small, isolated island communities. People could leave home if their islands suffered from famine, overcrowding, or wars. Less populated islands could be settled. Contacts with families, friends, and allies could be maintained. New knowledge, technologies, arts, and food resources could be exchanged. The kahuna Pa'ao, on the other hand, was said to have brought about greater social inequality, oppression, and conflict to Hawai'i, for he introduced from the Society Islands such things as human sacrifice, the red feather girdle as a sign of royal authority, the pulo'ulo'u kapu sign, the prostrating kapu, and the feathered war god Kaili.

After the 14th century, voyaging ceased for 600 years. It was revived in modern times by Hokule'a. The new voyagers had a new purpose: cultural revival and recovery. Voyaging has helped to bring back the extensive knowledge of land, sea, and sky that was once part of the Polynesian heritage; it has also helped bring back the traditions and practices that allowed resources to be used, yet conserved and protected.

(Sources: Fornander, "The History of Moikeha" Vol. 4, 112-158; Kamakau, Tales and Tradtions of the People of Old 3-5, 97-100, 105-110; Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology 352-375; Buck, Vikings of the Pacific 259-262)

Voyagers – Ancient and Modern

11. Kapena Clay Bertelmann

On the 1992 voyage to Tahiti, Hokule'a's kapena, or captain, was forty-seven year old Clay Bertelmann of Waimea, Hawai'i. Kapena Bertelmann first sailed with Hokule'a from Hawai'i to Tahiti in 1985; in 1986, he voyaged from Samoa to the Cook Islands, and in 1987, from Tahiti to Rangiroa. 1992 was his first voyage as kapena.

Bertelmann got involved with Hokule'a in 1978, the year the Tahiti-bound canoe was swamped in high seas and capsized. The canoe lost crew member Eddie Aikau, who left on a surfboard to get help and was never seen again. The loss of life made Bertelmann aware of the awesome responsibility of a kapena, and for 14 years, he was reluctant to accept a leadership role on the canoe. In 1992, however, Bertelmann accepted the responsibility for his family, especially his five children. The cultural recovery and strengthening that were the goals of the voyaging project were important to him. "We have an opportunity to learn what our ancestors did and how they did it," he explained, "and also an opportunity to share this with the younger generations."

Shortly before the 1992 voyage, his uncle Sonny took Bertelmann to a heiau in North Kohala and pointed out stones aligned in the directions of different destinations in the Pacific. Although Bertelmann had used this heiau as a landmark for crossings of the 'Alenuihaha Channel, this was the first time he was told of its navigational significance. For Bertelmann, this knowledge was part of the cultural recovery that was occurring, and also an acknowledgement that the time was right for him to take on the responsibility of kapena. Once he accepted the responsibility, he felt the burden of concern for bringing back safely each of his crew members to their families. The burden did not leave him until he landed in Honolulu on a flight from Tahiti in July with the last of his returning crew.

(Sources: Interview with Clay Bertelmann; Becky Ashizawa, "Hokule'a Poised for Tahiti Run," Star-Bulletin, June 15, 1992, A-1+)

12. Navigator Chad Baybayan

On Hokule'a's fourth voyage to Tahiti, Chad Baybayan shared navigation duties with Shorty Bertelmann. The thirty-five year old Baybayan first sailed with the canoe from Hawai'i to Tahiti and back in 1980. During the 1985-87 Voyage of Rediscovery, he sailed from Tahiti to Aotearoa and back, and from Tahiti to Hawai'i.

Baybayan was inspired to learn the art of wayfinding on the 1980 voyage to Tahiti while observing Nainoa Thompson practice the art. While Baybayan navigated on some short interisland trips in the South Pacific in 1986, 1992 was his first chance to navigate on a long voyage.

Before the voyage began, he felt the pressure of the challenge. However, he and Bertelmann did a superb job of guiding the canoe. The estimated positions reported each morning on KCCN Hawaiian Radio closely paralleled the canoe's actual course. While the navigators were about 170 miles farther west than they thought they were toward the end of the trip, they were well within the margin of error of their 400-mile-wide target screen in the Tuamotu and the Society Islands. The canoe hit the target screen dead center at the island of Mataiva.

Baybayan says that the most difficult part of the voyage was the doldrums, where shifting winds and heavy cloud cover made sailing and wayfinding difficult. The canoe, he says, had to tack five times in one day as the wind direction kept shifting. The shifting winds confused the swell pattern. "When you become confused by the swells," he explained, "you have to confirm your judgment by the movement of clouds on the horizon and the feel of the wind on your body." He estimates he slept only three hours a day on the 29-day voyage. Baybayan says the voyage was a matter of personal, family, and ancestral pride: "The statement we wanted to make was that we are the descendants of some very courageous and intelligent people."

(Interviews with Chad Baybayan; Bob Krauss, "Huahine turns out in warm welcome for Hokule'a Crew" The Sunday Star Sulletin & Advertiser, Sept. 27, 1992)

13. Navigator Shorty Bertelmann

Before Hokule'a left on its fourth voyage to Tahiti, 44-year old Shorty Bertelmann, like his co-navigator Chad Baybayan, wondered if he was fully prepared for the challenges of wayfinding on a long ocean voyage. Preparation involved not just memorizing nautical charts and star patterns, but watching the weather daily and thinking about the kinds of sailing decisions his teacher Mau and Nainoa would make at sea in response to the weather.

Bertelmann, the brother of kapena Clay Bertelmann, first saw Hokule'a in 1975 when it sailed into Kawaihae Harbor while he was helping to rebuild the walls of Pu'u Kohola heiau. Soon after that he met Mau and Nainoa. Bertelmann sailed from Hawai'i to Tahiti in 1976, when he began to learn navigation from being with Mau. In 1980 and 1985, from Hawai'i to Tahiti, he served as captain. He continued on the Voyage of Rediscovery from the Cook Islands to Aotearoa in 1985, from Samoa to the Cook Islands in 1986, and from Rangiroa to Hawai'i in 1987, serving as captain on each of these legs.

Bertelmann says the greatest challenge of the 1992 voyage was remaining continuously awake to keep track of the course of the canoe and watch the every-changing weather. By the time the canoe reached Tahiti, he had gotten the knack of catnapping in 3-4 minutes snatches, so he could regain his concentration-a technique he learned by observing Nainoa.

The highlight of the trip for Bertelmann was sighting a school of dolphins. On the voyage to Tahiti in 1985 Mau had sailed with Bertelmann, and they sighted a school of dolphins at about 10 degrees north latitude. Before the 1992 voyage, Mau, who was not going, told Bertelmann to look for the dolphins because they lived in that area of the ocean and would visit the canoe again. At about 10 degrees north, Bertelmann spotted the dolphins. It confirmed his faith and trust in Mau and the ancient tradition of navigation Mau represented. When he saw Mau again in Hawai'i, Mau asked him "Did the dolphins come visit you?" and Bertelmann answered, "Yeah."

(Source: Interview with Shorty Bertelmann)

14. Ho'okele-wa'a: The Traditional Navigator

Ho'okele-wa'a, literally "to sail, steer, or guide a canoe," was the title given to navigators of ancient times. Orals traditions record the names of some of these experts in astronomy, weather, winds, and sailing. Kamohoali'i, the shark god, guided his sister Pele's canoe to Hawai'i. Makali'i, "Eyes of the Chief," an expert in kilo hoku, or star-lore, guided the canoe of Hawaii-loa. Kane'apua was the name of the ho'okele who guided the O'ahu chief Wahanui to Kahiki and back; like Makali'i, Kane'apua "knew all the stars of the sky." Kamahualele guided the canoe of Mo'ikeha.

After the great age of long-distance voyaging ended in the 14th century, Hawaiian canoes sailed interisland. The best known ho'okele of this era was Paka'a, who was in charge of sailing and navigating the canoes of Keawenui-a-'umi, a ruling ali'i of the Big Island during the 16th century.

Paka'a's knowledge of sea and sky was extensive. According to historian Samuel Kamakau, Paka'a knew the coastlines of all the islands and the winds of each island, "the directions they blew in and the way they affected the ocean." He knew "how to manage a canoe out of sight of land," and "how to right a canoe that had overturned at sea." He was trained to read the signs of nature. "He knew how to tell when the sea would be calm, when there would be a tempest in the ocean, and when there would be great billows. He observed the stars, the rainbow colors at the edges of the stars, the way they twinkled, their red glowing, the dimming of the stars in a storm, the reddish rim on the clouds, the way in which they move, the lowering of the sky, the heavy cloudiness, the gales, the blowing of the ho'olua wind, the a'e wind from below, the whirlwind, and the towering billows of the sea."

(Sources: Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii 36; Kamakau Tales and Traditions of the People of Old.)

15. The Wind Gourd of La'amaomao

The traditional navigator had to know not just kilo hoku, or star lore, but the winds and the directions from which they blew. According to legend, the 16th navigator Paka'a could not only predict the wind and weather, he could actually control them with a wind gourd bequeathed to him by his kupunawahine La'amaomao, the wind goddess, whose name "Distant Sacredness" suggests the divine breathe which emerges from holes in the far horizon. This gourd held the dozens of winds of Hawai'i, and Paka'a could call forth the winds he wanted by chanting their names. The gourd contained the bones of La'amaomao.

The idea of a magical wind gourd, which also served as a wind compass, is traditionally Polynesian. One scholar notes that in Mangaia in the Cook Islands, "the high priest possessed a magic calabash, a miniature universe, which had 32 holes bored in a circle at equal distances around its middle." Each hole represented "the openings on the horizon through which the thirty-two winds of the compass were supposed to blow. When a voyage was planned to a distant island the priest was told to stop up all the holes in the calabash except the one in the direction from which the voyagers desired the wind to blow." Doing this would insure a favorable wind for the voyage.

In the Kalakaua version of the story of the voyager Mo'ikeha, a male La'amaomao is given the title "Director of Winds." This La'amamomao accompanied Mo'ikeha to Hawai'i from Kahiki and settled at Hale-o-Lono on the island of Moloka'i, where he was worshiped as an 'aumakua of the winds. Elsewhere in Polynesia, the wind deity is also male-Ra'a in the Society Islands, Raka in the Cook Islands, and Raka-maomao in New Zealand.

(Sources: Nakuina, The Wind Gourd of La'amaomao; Kalakaua, "The Triple Marriage of Laamaikahiki" in The Legends and Myths of Hawaii, 122; Makemson, The Morning Star Rises, 147)

The Art of Wayfinding

16. Wayfinding: Course Strategy

Hokule'a is guided by a system of wayfinding, or non-instrument navigation, devised by sailmaster Nainoa Thompson. It combines ancient techniques of navigation used throughout the Pacific with modern scientific knowledge. The wayfinding requires knowledge of the positions and geography of islands, the seasonal changes of weather and ocean currents between the islands, the character of winds and swells, the rising and setting points of stars and other celestial bodies, the habits of seabirds, and other phenomena of nature.

Before each voyage, the sailmaster devises a sailing plan and draws a reference course-the most efficient route between two islands, given the sailing capability of the canoe and the average winds, currents, and weather conditions along the route. However, the conditions encountered are never average, and the canoe normally departs from the reference course, sailing in the directions the wind will allow it to sail. After the voyage begins this reference course becomes a reference line, like the 0 degree longtitude line; the wayfinder mentally plots his position east or west of the line in units called houses, equal to 24 miles. When the wind carries the canoe east or west of the line, the wayfinder knows he'll have to eventually close the distance when the winds allow him to.

The sailing strategy also involves windward landfall. This means arriving at one's destination on its upwind side, so the canoe can sail downwind to its destination. If the canoe were to arrive on the downwind side of its destination, it would have to sail against the wind to reach its destination. That would mean tacking, or zigzagging back and forth into the wind, trying to make forward progress. The canoe can sail up to 200 miles in a day with the wind; against the same wind, the canoe would be lucky to sail 10 miles in a day.

17. Wayfinding: Holding Direction

After he devises a sailing plan, the sailmaster of the canoe chooses a tentative departure date to minimize the chances of encountering hurricanes and stormy weather. As the canoe sets sail on the first day of favorable winds, the wayfinder holds his course by backsighting on the island, lining up two landmarks astern. After the landmarks disappear below the horizon, the wayfinder depends on celestial bodies for directions.

The stars, the sun, the moon, and the planets rise in the east and set in the west at specific points on the horizon. The wayfinder has memorized the directions of these points. When he sees and identifies a star rising or setting, he knows what direction it is in and can determine all the other directions. For example, if he faces Mintaka in Orion's Belt, which rises due east, he knows west is on the opposite side of the horizon behind him, and north is to his left, south to his right.

The wayfinder also knows that the rising and setting points of celestial bodies change. The positions of all stars except those which rise due east and set due west change with changes of latitude. The rising and setting points of the sun change with the seasons. The moon, the closest celestial body to the earth, is the most changeable; its rising and setting points change nightly. The rising and setting points of the planets change more slowly since they are much farther away than the moon.

When clouds hide the stars, the wayfinder uses the ocean swells and the wind for direction. He keeps the canoe at a particular angle to the swells and the wind; the pitch and roll created by swells moving under the canoe help him feel the canoe's course. However, the swells and wind cannot be used by themselves for direction because their directions may change. The wayfinder must determine their direction from the rising and setting points of celestial bodies.

18. Wayfinding: Houses of the Horizon

To memorize the rising and setting points of two hundred stars, Nainoa Thompson has pictured the stars as inhabiting 32 directional houses, or segments, evenly spaced around the circle of the horizon: 'akau, or north; hema, or south; hikina, or east; and komohana or west are the four corners of the horizon. These four houses divide the horizon into four quadrants, which are named for winds that blow from these quadrants: The northeast quadrant is called Ko'olau; the northwest Ho'olua; the southwest Kona; and the southeast Malanai.

In each quadrant are seven houses:

- La, or sun, where the sun spends a good part of the year

- 'Aina, or land, where the zenith stars of Hawai'i and Tahiti rise and set

- Noio, named for the noddy tern, whose flight at sunrise and sunset indicates the direction from and to their home island

- Manu, or bird, the symbol of the canoe as it flies over the ocean swells on the wind

- Nalani, the chiefly one, named for Ke ali'i kona i ka lewa, "The chief of the southern skies"-the star Canopus, which rises and sets in this house

- Na Leo, or the voices of the stars which speak to the voyager

- Haka, or empty, the portions of the sky around the north and south celestial poles that are relatively devoid of bright stars useful in navigation.

In each of the thirty-two directional houses, stars and other celestial bodies wake up or rise, and go to sleep, or set.

He also knows as he travels north or south of the equator, stars, like people, will move houses, the northern stars moving north and the southern stars moving south. As the observer travels toward the north and south poles, the orbits of more and more stars appear above the horizon. The stars no longer rise or set, but begin to circle the celestial poles like the hands of a clock.

(Source: Kyselka, An Ocean in Mind, 95-97)

19. Wayfinding: Dead reckoning

Besides determining the heading of the canoe, the wayfinder also keeps track of how fast the canoe is going, how far it travels each day and where it is along its route. This technique of navigation, called dead reckoning, was used throughout the world before clocks, sextants, and almanacs, and later satellites, allowed a navigator to determine his position and heading precisely in terms of longitude and latitude.

The wayfinder knows his heading from celestial bodies. He compensates for leeway, or the angle at which the wind pushes the canoe off its heading. He calculates his distance travelled by multiplying the speed of the canoe by the time period the canoe travels at that speed. An experienced voyager can estimate speed by the amount of turbulence created by the canoe surging through the water and by the wind pressure against his skin; the less experienced can time bubbles or objects going past the canoe.

The wayfinder uses the sky as his clock; from one sunrise or sunset to another is 24 hours. Stars circling the celestial poles take twenty four hours to complete a circuit. The sun and stars that rise near east and set near west take twelve hours to go from horizon to horizon; or six hours from the eastern horizon to the meridian directly overhead, halfway across the sky, and six hours from the meridian back down to the western horizon.

The speed of the canoe fluctuates with the speed of the wind; and the heading of the canoe may change as well, so mental calculations of course made good can become quite complicated. Keeping track of the canoe's direction, speed, and distance travelled for up to 35 days at sea is the most mentally demanding part of wayfinding.

20. Wayfinding: Anticipating Wind and Weather

The wayfinder not only keeps track of his direction and distance traveled each day, he also tries to anticipate weather. He knows predominant weather patterns in each season for each region he crosses. Because he can only sail in the direction the winds allow him to sail, the wayfinder must exploit wind direction and shifts to get where he wants to go.

The wayfinder scans the horizon for signs of approaching weather. Puffy cumulus clouds indicate fair weather. Low gray clouds bring a fine drizzle. Thickening and darkening high clouds suggest a squall line or weather front is approaching, and that heavy rain or thunderstorms accompanied by high surface winds may follow. Cloud movements, shapes, and colors and the slant of the rain are clues to the speed and direction of the accompanying wind.

Satawal navigator Mau Piailug says if the clouds of an approaching squall are black, the wind isn't strong; if the clouds are brown, the wind is strong. High clouds mean not much wind, but maybe lots of rain. Low clouds bring lots of wind. As the squall line approaches, if the ocean beneath the clouds is black and the water is getting bumpier, a real strong wind is coming; if the ocean beneath the cloud is the same color as the ocean nearby, the wind is not strong.

Swells can help the wayfinder anticipate the strength and direction of wind far off; the larger the swell, the stronger the wind generating it; the wider the distance between swells, the farther off the wind. The wayfinder is always looking for signs of the ever-changing, invisible body of the wind making its presence and character known in the waves and swells, the clouds, even the flickering of stars. Whatever kind of wind and weather is coming, the wayfinder prepares his crew and canoe for it to use it to their advantage.

(Source: Kyselka, An Ocean in Mind 145)

At Sea

21. Dangers at Sea: The Legend of Rata

The ancient voyagers faced numerous dangers when they ventured out to sea in their canoes. The Tahitian story of the voyager Tumu-nui, king of Tahiti, lists eight dangers: isolated-coral-rock, sea-monster, long-wave, short-wave, fish-shoal, animal-with-burning-flesh, crane-empowered-by-Ta'aroa, and giant-clam-opening-at-the-horizon. On a voyage to visit his daughter on an island to the east, Tumu-nui was swallowed by the giant clam. The giant clam also swallowed the four brothers of Tumu-nui and a brother-in-law, Vahieroa, all of whom sailed to recover the bones of Tumu-nui. Finally, Tumu-nui's nephew, the giant Rata, son of Vahieroa, took up the quest of recovering the bones. The spirits of the upper woodlands built Rata a magic canoe and sailed it on the mountain breezes down to the lagoon, where he found it at sunrise beneath a rainbow.

After offerings to the land and sea gods, Rata received approval for his voyage from large sharks. He sailed past dangerous reefs, perhaps of Tuamotu islands, survived the long and short waves, and finally confronted the giant clam.

Peter Buck describes what happened next: "As the ship glided over the edge of the lower valve, the purple fringe, like monster tentacles, undulated forward and lapped against the sides of the vessel. The shining inner surface of the upper valve... loomed above them, poised for the downward plunge. Before it could fall, however, Rata and his men with one accord drove their spears ...[and] completely severed the great muscle that held together the upper and the lower valves. The huge upper valve that towered above the mast of the ship remained poised on its locked hinge, motionless and impotent. The body of the giant clam was cut open and in the interior were found the undigested bones of Tumu-nui and those who had followed after him."

Rata eventually destroyed six of the eight dangers of the sea, so that today, only two, long-wave and short-wave, indestructible elements of the ocean, remain to challenge voyagers.

(Source: Buck, Vikings of the Sunrise 92-97)

22. Dangers at Sea: Hokule'a

The most potent danger faced by the modern-day voyager are high winds and seas, which could flood the hulls, capsize the canoe, or break the mast or boom. Careful storm sailing procedures are designed to prevent these mishaps from occurring.

Closing the sails in heavy seas

Other dangers include fire, man overboard, and serious injury or illness. A medical doctor is usually included among the crew to handle medical problems or emergencies.

Crew safety is the highest priority. The crew is screened for good health, physical conditioning, and the ability to swim and stay afloat in the open ocean. The crew is trained to handle the canoe in rough ocean conditions, and the canoe is stocked with safety equipment, including water-pumps, fire extinguishers, life jackets, safety harnesses and nets, and a man-overboard float tethered to the stern of the canoe. Radio equipment allows for communication with an escort boat or land stations. In 1992, Hokule'a was escorted by Kamahele, a steel ketch built by and under the command of Alex Jakubenko, who also skippered the escort boat for Hokule'a's 1980 voyage.

The 1992 voyage was a relatively safe one. Two experiences during the 1985-87 Voyage of Rediscovery illustrate life-threatening situations and how they are handled. While sailing from Aotearoa to Tonga, a crew member fell overboard in the night when his safety harness broke while he was leaning over the side of the canoe. Luckily navigator Nainoa Thompson saw his hat float by and sounded the alarm. Part of the crew scrambled to stop the canoe by letting the wind out of the sails; the others threw in the man-overboard float. The crew member swam to the float and was pulled back to the canoe.

On the voyage home in 1987, a crew member developed a skin infection; as he was allergic to penicillin and none of the other medicines on the canoe worked to stop the infection, the captain finally had to radio for help and the injured crew member was taken off the canoe by the U.S. Navy.

(Source: Interview with Bernie Kilonsky)

23. Provisioning the Canoe

Like an ancient voyaging canoe, Hokule'a is relatively a self-contained environment. It has to take with it what the crew needs to survive for the number of days at sea, though food and water can be supplemented by fish and rain caught during the voyage.

The canoe has a displacement of about 12.5 tons. It weighs 7 tons with its rigging, so it can carry an additional 5.5 tons-which would include the weight of the crew, as well as the weight of provisions, supplies, and personal gear.

On long voyages the crew is limited to thirteen or fourteen people; the canoe packs enough food and water for the crew, plus something extra. On 1992 voyage to Tahiti, for example, which was estimated to take about 30 days, the canoe left with 35 days of food and water.

Food consists mainly of canned, packaged, and dried foods, and weighs about a ton. About one-and-a-half tons of water are stored in five-gallon plastic jugs. The crew eats three meals and is allotted one quart of water per day. During the voyage, the captain monitors how much is being consumed. If the voyage is taking longer than expected because of unfavorable winds, the food and water are rationed. However, dehydration can be a problem in hot, humid weather, so water has been rationed only twice in the history of Hokule'a voyaging. Rainfall, caught in tarps, helps replenish the water supply.

The quartermaster must evenly distribute the weight of the supplies and be careful not to overload the canoe because uneven distribution of weight or overloading would reduce the canoe's manuveurability and increase the possibility of swamping. On the 1992 voyage, quartermaster Harry Ho and the captains supervised the provisioning and loading of the canoe.

(Source: Crew Training Manual; Manifest of the Hokule'a)

24. Fishing on Hokule'a

The only way to supplement food supplies on an ancient voyaging canoe at sea was to catch fish, and possibly birds. Fishing was a matter of survival. In the same tradition, fishing is more than just a pastime on Hokule'a. A good-sized fish provides a day or two of food for the crew and allows the crew to conserve its supply of food and lengthen the time the crew can survive at sea.

Ono, flanked by mahimahi

One crew member on board the canoe serves as a designated fisherman, responsible for putting out the lines at sunrise, bringing in the catch with the assistance of other crew members, and pulling in the lines at sunset. On the 1992 voyage, Nailima Ahuna,Tiger Espere, Terry Hee, and the Cook Islanders who joined the Hokule'a crew in Ra'iatea served as head fishermen.

Hokule'a trails four 400 pound-test fishing lines, with lures attached. Two of the lines extend out from each side of the canoe on bamboo poles to prevent the lines from tangling. The canoe needs to be travelling at around 6-7 knots for good results. The crew catches a range of open ocean fish, including aku, ahi, mahimahi, ono, and a'u, or marlin. On the 29-day voyage to Tahiti, 35 fish were caught; on the 35-day voyage home, 27 fish were caught, including a 150-pound and a 200-pound marlin.

The catches are especially appreciated by the crew because fish is the only fresh food eaten after the fresh fruits and vegetables have been consumed, usually within the first few days. The fish is eaten raw, marinated for po-ke, or fried. The leftover fish parts and bones are used to make soup. Leftover strips of meat are dried from the rigging, then put into buckets as snacks for the crew.

(Source: Journal of Mike Tongg; interviews with Nailima Ahuna and Bruce Blankenfeld)

Sailing in Tahiti (Sept. 1-Sept. 19, 1992)

25. Tautira, Tahiti

Two days after landing in Papeete, Tahiti, on July 15, Hokule'a sailed to the village of Tautira, where the canoe would be tied up at a small harbor for two months, awaiting the continuation of the voyage for education in mid-September.

Tautira is a small town at the end of the paved road on the northeastern end of the island of Tahiti. Its location and character reminds one of Hana, Maui; like Hana, it's at the opposite end of the island's urban and tourist development and retains a rural and fishing life-style.

Sol Kahoohalahala on the shore of Tautira, 1992

The Polynesian Voyaging Society and Hokule'a have a special relationship with Tautira. The canoe first stopped there for festivities in 1976 during its voyage around the island Tahiti. Before the 1980 voyage to Tahiti, Puaniho Tauotaha, a canoe-carver from Tautira, made several canoes in Hawai'i and demonstrated the ancient art of canoe carving to interested members of the Voyaging Society.

Puaniho Tauotaha. KS Archives

The Maire-nui Canoe Club of Tautira, once the champions of all Tahiti, have raced in Hawai'i, and some clubs in Hawai'i have adopted their training and racing techniques. And before sailing back to Hawai'i in 1987, the Hokule'a crew stayed in Tautira waiting for the right winds; the friendships established then have lasted over the years.

House in Tautira, c. 1987. KS Archives

On September 1, 1992, a new crew under Kapena Billy Richards arrived in Tautira to continue the Voyage of Education. The crew was charged with doing repair and maintenance on the canoe and loading the canoe with water and food supplies, then sailing it to the islands of Huahine and Ra'iatea, where a ceremony was planned at the marae of Taputapuatea. During its one-and-a-half week stay in Tautira, the crew was divided into three groups, and each group was hosted by a family (Puaniho and Mahine Tauotaha; Terevaura and Octaze Tihoni; and Robert and Mary Wahler); Tautira town mayor Sonny Matehau and his family provided breakfast and dinner for the crew each day.

26. A Day of Rest

The week-and-a-half stay in Tautira was busy for the Hokule'a crew. A leak in the starboard hull had to be located and plugged. Cracks in the fiberglass had to be repaired. Wear and tear on the mast footing and booms had to be sanded and varnished. An additional navigator's platform had to be built. The radio and other electronic equipment had to be reinstalled. The canoe had to be loaded with supplies and water.

Tiger Espere, Tautira

Sunday, however, was a day of rest. In the morning, the crew members accompanied the families hosting them to church, to worship and to enjoy the superb singing of the choirs of Tautira. In the afternoon, the crew relaxed or went sightseeing, swimming, or hiking. Two boatloads headed for the pali along the coast south of Tautira. There among the shadows of the hau trees along the narrow shore beneath the steep, lush green cliffs are petroglyphs that attest to the voyaging traditions of Tautira. On one large moss-covered stone an image that resembled a canoe with a sun on its sail, the rays of light radiating out like spokes. On another stone were three images of the radiating sun-one rising, one standing overhead at noon, and one setting-essential positions for the navigator in determining time and direction. On a third stone were curved lines suggesting the wings of seabirds in flight.

Offshore is a small motu, or island; between the motu and shore, crew members went spearfishing, or dove for shellfish. Kapena Billy Richards noted there was more fish the last time he was there in 1976, and speculated that the development of houses along the coastline was killing the reef. As the crew motored back in the glowing warmth of the afternoon sun, Tahitian Robert Wahler taught the crew how to pry open the shellfish and pull out the meat, which was sliced into pieces and eaten raw.

27. Sail from Tahiti to Huahine

Hokule'a departed from Tautira for the island of Huahine on the morning of September 10. The send off was an emotional one. A few days earlier a stone statue had been placed on the shore of Tautira Bay to commemorate a marae named Taputapuatea that once existed nearby, an offshoot of the marae in Ra'iatea. Townspeople and schoolchildren gathered around the stone god to bid farewell to the canoe with songs and dances. After last hugs and exchanges of gifts, Hokule'a set sail with a light southeast tradewind at its stern. Huahine lay about 150 miles to the northwest.

On this sail, the canoe was navigated for the first time by Keahi 'Omai.

Keahi Omai. Photo by Kapulani Landgraf

He backsighted on the peak of Maire-nui in Tautira for most of the day, keeping it dead astern. As evening fell the stars Hokule'a (Arcturus) and Hikianalia (Spica), setting ahead of the canoe, provided clues to direction. Later, Ka-maile-mua and Ka-maile-hope (Alpha and Beta Centauri) setting on the port beam were guides. Because the night sky was often cloudy, the steersmen also used the ocean swells to orient the canoe, two swells from the northeast and one from the southeast rolling under the canoe from stern to bow. For confirmation of the canoe's heading, 'Omai waited for the appearance of the constellation Iwakeli'i, or Cassiopeia, which he expected to rise off the starboard beam about two hours before midnight. The appearance of this constellation confirmed his course. After midnight, a whole set of navigation stars called Ke Ka o Makali'i ("The Canoe Bailer of Makali'i") rose in the east behind the canoe. While these stars were rising, 'Omai sighted Huahine faintly lit by moonlight in the direction pointed out by sailmaster Nainoa Thompson. Before sunrise, he also sighted in the light refracted over the eastern horizon the outline of the island of Tahiti, which had already disappeared from view.

In the morning, the green hills of Huahine appeared dead ahead of the canoe; the excitement of landfall was tempered, however, by a radio report that Hurricane Iniki was heading for Kaua'i.

Kapena Billy Richards with Gil Ane, peeling pamplemousse (grapefruit) and laughing, offshore of Huahine. They just played a game of bowling, in which the pamplemousse served as balls.

(Source: Interview with Keahi 'Omai)

28. Huahine – Dr. Yoshihiko Sinoto and Polynesian Archaeology

The island of Huahine, 150 miles northwest of Tautira, was the first stop on the second leg of Hokule'a's Voyage of Education. As the canoe approached the harbor of Fare, it was greeted by four six-man racing canoes and a motorized double-hulled canoe. The welcome continued on shore with speeches, dancing, and singing. Schoolchildren from Huahine were given a tour of the canoe, and crew members later visited a school to talk to the students about voyaging traditions.

While in Huahine, the canoe was anchored off the Bali Hai Hotel, near the site of an important archeological discovery. In 1979, Bishop Museum Archeologist Yoshihiko Sinoto found the remains of an ancient voyaging canoe-two 23-foot planks from the hull, a 12-foot steering paddle with a six-foot blade, and a 36-foot mast. These remains were embedded and preserved in the swampy land overgrown with hau trees and rushes near the hotel. The canoe parts were dated between 850-1000 A.D.

Dr. Sinoto excavating a voyaging canoe on Huahine

When Hokule'a arrived on Huahine, Dr. Sinoto and his staff were there to restore the Mata'ire'a Hill Complex at Maeva on the north end of Huahine, an area where the chiefs of Huahine used to live along the fish-rich lagoon and in the fertile uplands.

Unlike on most islands in Polynesia, where the chiefs lived in separate valleys or districts, the chiefs of Huahine lived together in one area after the island was unified under one ali'i family. At Maeva are concentrated dozens of closely situated marae, house foundations, burial platforms, and agricultural terraces. The mile-long trail through the complex begins at a wall where the people of Huahine resisted the French marines who landed on the island in l846. The trail goes past the Marae Mata'ire'a-rahi, an ancient community marae shaded by a huge sacred banyan tree, and culminates at the Marae Paepae Ofata, built on a dry, fern-covered hillside with a spectacular view of the lagoon and its fish runs, the coconut-tree lined shore and offshore island, and in the distance, Huahine-iti, the southern half of the island.

(Source: Interview with Elaine "Muffet" Jourdane)

The lagoon at Maeva, from Marae Paepae Ofata

29. Ra'iatea: The Heart of Central Polynesia

Hokule'a left Fare on Huahine before dawn on September 16. Its next stop was the marae of Taputapuatea in the district of Opoa on the southeastern end of the island of Ra'iatea. Ra'iatea is eighteen miles east of Huahine, easily seen across a channel, with the downwind islands of Taha'a and Borabora beyond Ra'iatea to the northwest.

The shore of Taputapuate, in the district of Opoa, Ra'iatea

Ra'iatea, anciently called Havai'i, is considered the homeland of central Polynesian ali'i culture and a major center of Polynesian religion and learning. On this island in the district of Opoa, Peter Buck tells us, "The priests...gathered the warp of myth and the weft of history together and wove them into the textile of theology." The general pattern of Polynesian religion was developed there, with a Sky father (Atea or Wakea) and an Earth mother (Papa) giving birth to children who had special functions: Tane, or Kane, foresty and craftsmanship; Tu or Ku, war; Ro'o, or Lono, peace and agriculture; Ta'aroa, or Kanaloa, marine affairs and fishing; and Ra'a, or La'a, wind and weather. In the district of Opoa, houses of learning were established, where scholars could study religion, genealogies, heraldry, and oratory, as well as astronomy, geography, and navigation.

From this island in central Polynesia, the pattern of ali'i culture was carried abroad on voyaging canoes by adventurers, conquerors, and colonizers-west to the Cook Islands and Aotearoa, or New Zealand; south to the Austral Islands and Rapa; east to the Tuamotus, the Marquesas, and Rapanui, or Easter Island, and north to Hawai'i.

Image from Peter Buck’s Vikings of the Pacific, p. 88

Laniakea on O'ahu's north shore is the Hawaiian form of Ra'iatea; at Laniakea was a heiau named Kapukapuatea, which was a navigation heiau, like the marae of Taputapuatea in Ra'iatea; at Poka'i Bay in Wai'anae is Ku'ilioloa heiau, also associated with navigation and built by the same priest who built Kapukapuatea. Perhaps Kapukapuatea in Laniakea was founded with a stone taken from the marae of Taputapuatea in Ra'iatea, as was the custom. Since Kapukapuatea no longer exists, a stone from Ku'ilioloa in Wai'anae was carried on board Hokule'a in 1992, as a gift for the return home.

(Source: Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, 87-90; Handy, History and Culture in the Society Islands, 87)

30. Taputapuatea – The Rise of 'Oro

The district of Opoa in Ra'iatea eventually became the center for the worship of the war god 'Oro. 'Oro, son of Ta'aroa, or Kanaloa, is said to have been born in Opoa. The marae of Taputapuatea became dedicated to him. Human sacrifices, first made to Ta'aroa to free the island from a severe drought, increased when the more demanding god 'Oro began to be worshiped.

The cult of 'Oro spread to other islands of the region, sometimes through peaceful persuasion, but more often through conquest. An international alliance eventually formed in the region, and its meeting place for religious observances and political deliberations was Taputapuatea. From the eastern and southern islands, called Te Ao-uri, or "Blue lands," came canoes from Huahine, Tahiti, Mai'ao, and the Austral islands; from the western islands, called Te Ao-tea, the "White lands," came canoes from Rotuma, Taha'a, Porapora, Rarotonga in the Cook Islands and Aotearoa, or New Zealand. On an appointed day, the canoes entered the sacred pass of Te Ava Moa in double file, the canoes of the blue lands on the south side and the canoes of the white lands on the north side.

One of the meanings of "Tapu-tapu-atea" is "Sacrifices from abroad." On the deck of each canoe were offerings to 'Oro, including human sacrifices, laid out alternately with ulua, shark, and turtle. The canoes were brought ashore using human corpses as rollers. On shore, the human sacrifices were drilled through the head and hung by sennit from the trees while the gods of each of the islands were brought into the inner sanctum, where an image of 'Oro was kept-a figure woven of sennit covered with red and yellow feathers and wearing a girdle of red feathers; then the most sacred of all the rites took place, the pai-atua, or assembly of the gods.

At the time of these sacred rites, kapu were enforced, and a hush came over the land; no fires were lit, no food eaten. After the ceremony was over, the kapu were lifted, and the people could breathe freely and eat again.

(Sources: Henry, Ancient Tahiti, 119-125; Handy, History and Culture in the Society Islands, 86-91)

31. Taputapuatea – The Oppression of 'Oro

According to oral traditions, Tahiti and the other upwind islands in the Society group were created from the land between the islands of Ra'iatea and Taha'a. The story goes that kapu were imposed on the the district of Opoa in preparation for a ceremony for 'Oro worship: no cock could crow, no dog bark; no person or pig could leave its dwellings. The wind died off and the sea grew calm. However, a young girl named Tere-he went bathing in a river. The gods drowned her for breaking the kapu. A giant eel swallowed her and was possessed by her soul. The angry eel tore up the land between the two islands and swam off. This gigantic fish swam to the east and became the windward island of Tahiti; its back fin formed the mountain of Orohena, which dominates the western end of Tahiti. Another fin fell off and became the island of Mo'orea. Other bits of the fish became the islands of Meti'a, Te Tiaroa, and Mai'ao-iti.

Anthropologist Peter Buck interprets this story as meaning that the people who settled these windward islands, and who later migrated to other islands like Hawai'i from them, had fled Ra'iatea because of the oppressive, tyrannous rule of the priests of 'Oro. Perhaps the drowning of Tere-he was an actual event that caused her people to flee. It wasn't the land that swam away, but the people who sailed off in canoes.

Eventually, the international alliance that centered on 'Oro worship at the marae of Taputapuatea also fell apart in bloodshed. The priest of the white lands to the west was slain by a high chief of the blue lands to the south and east. The priest of the blue lands was struck down in retaliation, and the two sides parted, never again to reconvene their meetings at the marae.

(Sources: Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, 76-78; Henry, Ancient Tahiti, 126-7)

32. The Lifting of the Kapu – 1985

When Hokule'a first visited Tahiti in 1976, the crew took the canoe to Taputapuatea on the island of Ra'iatea to pay homage to the voyagers who had set forth from there during the great migrations of the 12th to 14th century. However, Hokule'a came to the marae through the shipping channel near the port town of Uturoa rather than through Te Ava Moa, "The Sacred Pass," through which the ancient canoes traditionally came to the marae.

According to the traditions of the cultural group Pupu Arioi, the last canoe to leave Taputapuatea was Hotu Te Nui. It sailed to Hawai'i and left behind a kapu on the sacred pass. Since that time-centuries ago-all the canoes from Mo'orea which had tried to sail to the marae had failed to reach their destination. The Pupu Arioi believed that only when a canoe from Hawai'i returned to the marae through the sacred pass could the kapu be lifted. The group conveyed this message to the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

So it was that in 1985, on the Voyage of Rediscovery, Hokule'a lifted the kapu which prevented the Mo'orea canoes from reaching Taputapuatea. After a fire-walking ceremony for purification and other ceremonies on the island of Mo'orea, Hokule'a sailed to Ra'iatea under Navigator Nainoa Thompson and Kapena Gordon Pi'ianai'a. A rainbow appeared ahead, and the canoe glided toward its center, as if guiding itself, as it sometimes does when the wind is on its beam. The steering paddle was taken out of the water and tied down. Eventually Ra'iatea appeared beneath the rainbow. Crew member John Kruse reported everyone got "chicken skin." When the crew landed, the people of Ra'iatea greeted the returning descendants with song.

(Sources: Kane, "The Seekers"; Letter from the Pupu Arioi to the Polynesian Voyaging Society 1985)

33. Reconciliations – 1992

In 1992, Hokule'a left Fare harbor on Huahine bound for Ra'iatea in the early morning of September 16 to participate in a ceremony planned at the marae of Taputapuatea.

The skies were dark with rainclouds, and although a large swell was coming from the southeast, the southeast trades were being held off by a weather front to the west. Because of the light winds, the canoe was towed across the channel by its escort boat Kamahele. As the canoe approached Ra'iatea, misted in rain and under layers of dark grey rainclouds, a rainbow arched above the sacred pass.

From offshore, the crew sighted an 'iwa, or frigate bird, the shadow of 'Oro, soaring above the marae. Na'ia, or dolphins; honu, or turtles; and mano, or sharks, were also sighted as the canoe approached land. All of these were signs of reconciliation to take place. On board Hokule'a were Hawaiians and Tahitians, descendants of some of the Ra'iateans who had fled the oppression of 'Oro 500 years earlier; also on board were Cook Islanders and Maoris, descendants of the people whose priest had been slain at Taputapuatea.

Hokule'a was paddled through Te Ava Moa.

The crew landed and was challenged, then greeted by the Ra'iateans after the good will of the visitors was established. As the crew marched toward the marae past the nine-foot high stone of chiefly investiture, a heavy downpour began.

Investiture Stone

One observer pointed out a stone called the queen, and another one known as the bird. "The queen," she said, "has not spoken since the ancient navigators deserted Taputapuatea. Today she is weeping tears of joy because they have returned. Her tears are washing away the kapu that have kept us from the marae. Now the bird is flying out through the sacred pass to spread the word to all the people of Polynesia."

Marae at Taputapuatea

A prophecy was fulfilled: according to oral tradition, the kapu imposed when the last canoe of people fled the marae 500 year ago could only be lifted when the descendants of those who had fled returned in search of knowledge and for peaceful and spiritual purposes. Now that the descendants were returning, the people of Ra'iatea who had been silenced by the kapu and who were spiritually asleep were reawakened. The children could laugh again, and the people sing. The heavy downpour seemed to signify that the ancient period of human sacrifice, which had begun with the attempt to persuade the god Ta'aroa to end a severe drought, was finally at an end.

(Sources: Interview with Nalani Minton; Bob Krauss, "Canoe gathering enriches island culture," The Sunday Star Sulletin & Advertiser, Sept. 27, 1992)

34. The Pahu Drum and the Hula

The crew of Hokule'a arriving at Taputapuatea in 1992 brought the gift of a drum, fashioned by Keone Nunes of Wai'anae from a coconut trunk, the drumhead lashed on in the tradtional style. The drum, called "Poki'i," "younger brother or sister," was a descendant of the drum introduced to Hawai'i centuries ago by La'a-mai-kahiki, son of Mo'ikeha, some say from Ra'iatea, others say from the northwest region of Tahiti ruled by the 'Oropa'a or Olopana clan. The drum, for the Ra'iateans and Tahitians, was a sacred gift because its beat represents the heartbeat of the land and the people.

Drawing by Melanie Lesset

According to the Fornander version of the La'a-mai-kahiki story, the drum was brought on La'a-mai-kahiki's second visit to Hawai'i. He was returning to Hawai'i to get the bones of his father Mo'ikeha for burial in the southern homeland. As his double-hulled canoe approached Ka'u, the people heard the beating of a drum and the playing of bamboo flute for the first time. La'a-mai-kahiki moored his canoe at Kailiki'i in Ka'u, where the people greeted his canoe as the canoe of the god Kupulupulu. They prepared a feast and invited the voyagers ashore. When La'a-mai-kahiki went to Kona, he was again feted. He was said to have introduced to Hawai'i at this time both hula dancing and drumming. La'a-mai-kahiki continued on to Kaua'i, then toured all the other islands, teaching the arts of drumming and dancing. With his brother Kila, he eventually took his father's bones back to Tahiti.

In 1992, the Kamehemeha Schools dancers who performed at Taputapuatea under the direction of Randie Fong and Kalena Silva performed hula to the pahu drum as a tribute to the Tahitians who had introduced the drum and the hula to Hawai'i. The performance was another connection in the cycle of the return of the descendents to the ancestral homeland.

(Sources: Interview with Keone Nunes; Fornander, "The History of Moikeha,"112-162)

[Kamakau's version of the story of La'amaikahiki has the canoe landing at at Na-one-a-La'a, the sands of La'a, in Kane'ohe, O'ahu, rather than Kailiki'i. A man named Ha'ikalama tricks La'a into showing him the drum so he can make a likeness of it.]

35. A Meeting of Navigators at Opoa

The district of Opoa on the southeastern end of the island of Ra'iatea was one of the centers of Polynesian migration. At this center of learning, ancient navigators leaving for distant islands met to exchange knowledge.

In 1929, during a Bishop Museum expedition, Anthropologist Peter Buck visited the marae of Taputapuatea in Opoa. There among the ruins he lamented the lost of the Polynesian spirit:

I had made my pilgrimage to Taputapu-atea, but the dead could not speak to me. It was sad to the verge of tears. I felt a profound regret, a regret for – I know not what. Was it for the beating of the temple drum or the shouting of the populace as the king was raised on high? Was it for the human sacrifices of olden times? It was for none of these individually but for something at the back of them all, some living spirit and divine courage that existed in ancient times and of which Taputapu-atea was a mute symbol. It was something that we Polynesians have lost and cannot find, something that we yearn for and cannot recreate. The background in which that spirit was engendered has changed beyond recovery. The bleak wind of oblivion had swept over Opoa.

On the morning of September 17, 1992, over sixty years after Buck's visit, a meeting of navigators, the first in over 500 years, took place in the cafeteria of the community center at Opoa, where the crew was housed, near the marae of Taputapuatea.

Four navigators from Hawai'i, seven from the Cook Islands, and one from New Zealand discussed their sail plans and course strategies for voyages they were about to make, or had already made. It was a final class in navigation and a rite of initiation for those embarking on their first voyages. The meeting was presided over by navigator Nainoa Thompson; also in attendance was his teacher Mau Piailug, the master navigator from Satawal in Micronesia. The meeting was a way of showing Piailug that his knowledge of wayfinding was being passed on to others, that this knowledge, once planted by his teaching, had taken root, branched, leafed, flowered, and was now bearing fruit. Taputapuatea, which may mean "sacredness radiating outward," had once again become a place of learning. After spending 17 years recovering the ancient knowledge of voyaging and navigating, Thompson had begun to recreate what the anthropologist Buck had lamented was lost forever-the "living spirit and divine courage that existed in ancient times."

(Source: Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, 85)

36. Kapena Billy Richards

Hokule'a's Kapena in the Society Islands was Billy Richards, a crew member on the canoe's first voyage to Tahiti in 1976. During that historic voyage he and other Hawaiians came into conflict with the haole crew members. The conflict stemmed from two very different views of the voyage: for the haole, the voyage was a scientific experiment to learn the techniques by which Polynesians had explored and settled the Pacific; for the Hawaiians, the voyage was an highly emotional journey toward cultural reawakening. The crew's frustrations in preparing for Hokule'a's first long voyage, and the hardships and inequities during that voyage aggravated their differences. After landfall, both sides vented their frustration and anger, which eventually erupted in physical hostilities on board the canoe.

Bill Richards. Photo by Kapulani Landgraf

Richards was portrayed as one of the instigators of the clash, so although he had been chosen as the kahu of the canoe prior to its departure from Hawai'i, the Polynesian Voyaging Society did not allow Richards to sail on Hokule'a when it made its first visit to Taputapuatea in the summer of 1976. Instead, Richards was taken to the marae by a man from Huahine who had been hanai to his family. Richards participated in the ceremony at Taputapuatea first by making sure that everything was pono with the spirit of the marae, and then by reciting the names of his fellow crew members, for he was also there to represent them. Still, his presence was not looked upon with favor by the Voyaging Society.

Now Hokule'a's Kapena, Richards saw the 1992 sail from Tautira to Taputapuatea as the closing of a circle-the completion of his 1976 voyage. The anger was gone. In 1985, he had sailed as a watch captain on Hokule'a from Rarotonga to Aotearoa with Dr. Ben Finney, one of the targets of his anger in 1976. Although some were concerned he still felt some hostility toward Finney, Richards assured them that he had already made things right through self ho'oponopono.

In September of 1992, as the rain poured down on the marae of Taputapuatea, Kapena Richards saw a cleansing occuring; the rain was washing into the purifying sea the centuries-old blood of past human sacrifice; for him, the cleansing had already taken place within.

(Source: Interview with Billy Richards)

Sailing in the Cook Islands (Sept. 20-Oct. 25)

37. Landing at Mauke