Ku Holo Komohana: 2007 Voyage to Japan

Time Line and Map of the 2007 Voyage

On April 12, 2007 Hokule'a and its escort boat Kama Hele departed from Colonia, Yap, for Okinawa and Japan.

-

Departed Colonia, Yap on April 12; Arrived at Itoman, Okinawa on April 23

-

Departed Okinawa on April 29; Arrived at Amami on April 30

-

Departed Amami on May 2; Arrived at Uto, Kumamoto on May 4

-

Departed Kumamoto on May 7; Arrived at Nomozaki on May 7

-

Departed Nomozaki on May 8; Arrived at Nagasaki on May 8

-

Departed Nagasaki on May 11; Arrived at Fukuoka on May 11

-

Departed Fukuoka on May 19; Arrived at Oshima, via Shinmoji (overnight) and Iwaijima, on May 20

-

Departed Oshima on May 23; Arrived at Hiroshima, via Itsukushima/Miyajima (overnight), on May 24

-

Departed Hiroshima on May 27; Arrived at Uwajima on May 28

- Departed Uwajima on June 4; Arrived in Yokohama, via Muroto (overnight) and Miura (two nights), on June 9

Background and Introduction

Ku Holo La Komohana (“Sail On to the Western Sun”), Hokule‘a's 2007 Voyage to Japan, took place to honor and perpetuate historic cross-cultural connections and intercultural exchanges between Hawai’i and Japan which followed King David Kalakaua's 1881 Journey to Japan. Hokule‘a sailed to Japan from Yap, in the Federated States of Micronesia, at the completion of Ku Holo Mau (“Sail On, Sail Always, Sail Forever”), the 2007 Voyage to Satawal, arriving in Okinawa on April 23

Kalakaua's 1881 Journey to Japan

In 1881, King David Kalakaua was the first head of state to visit with Emperor Meiji after the opening of Japan in 1854. Kalakaua was elected to rule Hawai'i by the Hawaiian Legislature in 1874 and reigned until his death in 1891; Emperor Meiji ruled Japan from 1867 until his death in 1912.

King David Kalakaua (1836-1891; ruled Hawai'i from 1874 to 1891)

Kalakaua traveled from Hawai'i on the City of Sydney, Kalakaua boarded the Oceanic in San Francisco; twenty-four days later, on March 4, he and his traveling party landed at Yokohama in Edo (Tokyo) Bay, where he was greeted with a 21-gun salute and a military band playing the Hawaiian National Anthem. The king and his party were astonished that the band had learned to play their anthem. The houses of Yokohama displayed Japanese and Hawaiian flags. (Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his World, 1852-1912 by Donald Keene [New York: Columbia University Press, 2002].)

SS Oceanic

"King Kalakaua wrote back from Tokyo on March 15, 1881, 'Our reception has been most cordial and pleasant with the Emperor [Meiji]. He extended the hospitality of being his guest during our stay in the City of Tokio, occupying the same buildings that General Grant did when he was here and other distinguished guests, Prince Henri of Germany and the Duke of Genoa.' The subject of possible Japanese emigration to Hawaii received some consideration by the Japanese officials. And on February 8, 1885, the first group of Japanese immigrants (676 men, 159 women, and 108 children) came to Hawaii. Major credit for this successful endeavor was due to 'the personal friendship of the Emperor of Japan for King Kalakaua,' commented the editor of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser" ( "A Hawaiian King Visits Hong Kong, 1881" by Tin-Yuke Char).

During his visit to Tokyo, Kalakaua also secretly discussed with the Emperor the possibility of forming a league of Asian countries to oppose the domination and oppression of European countries. Kalakaua said that he would propose the league to the leaders of China, Siam, India, and Persia on his world tour, if Meiji would agree to head the league. Meiji was understanding, but pointed out that China wouldn't join if Japan was leading the league; but he would consider the King's proposal and send a response. After conferring with his cabinet, Meiji declined the offer of leadership for the initiative. (Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his World, 1852-1912 by Donald Keene.)

Still the two heads of state saw the importance of building global relationships and the value of cultural exchanges. Kalakaua requested and Meiji signed an agreement in 1885 allowing the immigration of Japanese workers to Hawai‘i.

Emperor Meiji (1852-1912; ruled Japan from 1867 to 1912)

The result has been cultural exchanges between Hawai‘i and Japan, and intercultural lives. The issei (first generation immigrants) and their descendants have contributed to the growth and well-being of a multicultural community in Hawai‘i.

Hokule'a's voyage to Japan will nurture multi-generational, multicultural family ties and provide an opportunity for cultural exchanges, with Hawai'i sharing with the Japanese the story of Hokule'a and the renaissance of Hawaiian culture and pride. The voyage will also celebrate Hawai‘i’s cultural diversity, honor our ancestors, encourage stewardship of our environment, and contribute to global peace by fostering cultural understanding and appreciation.

Kalakaua's Global Vision

King David Kalakaua (1836-1891) is well known today as a patron and revivalist of Hawaiian culture and arts, including the hula, chanting, and oral narratives. Less well known is his global vision, accompanied by his efforts to establish international relationships between his kingdom and foreign governments. During his reign as monarch (1874-1891), he worked to maintain the independence of Hawai'i by learning as much as he could about how other nations developed and remained strong in a competitive global environment. He was the first monarch in history to travel around the world.

At the start of his world tour, in 1881, King David Kalakaua traveled from San Francisco to Yokohama and met with Emperor Meiji; the king was the first head of state to meet with the emperor after the opening of Japan in 1854. Kalakaua saw in Japan an island nation that was modernizing and able to remain independent despite the proximity of larger nations like China and Russia. He was impressed by Japan’s military forces and technology adapted from the West and conceived of the idea of an alliance with Japan for the protection of his kingdom against foreign powers. He proposed a future marriage between the five-year old Princess Ka’iulani and Prince Komatsu of the Japanese imperial family.

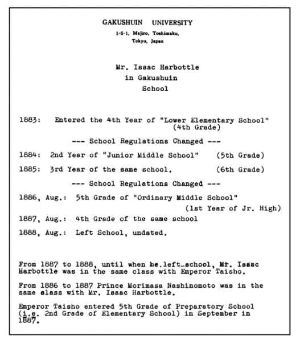

Although the imperial family had already arranged a marriage for the prince, Kalakaua continued to build ties with the Japanese. He started Hawai’i’s first study abroad program and sent young Hawaiian scholars to Japan (and China, Britain, Scotland, Italy, and America). The two students he sent to Japan were James Haku’ole and Isaac Harbotttle, brothers, 11 and 10 years old, who grew up in Kipahulu Maui. The two boys arrived in Japan in 1882 to study the Japanese language and culture at Gakushuin University, also known as the Nobles School (Kuwazoku Gakko), with the aim of using their knowledge to assist in international affairs and the establishment of an immigrant worker program. This program was established in 1885 and led to the immigration of Japanese workers to Hawai’i.

Isaac Harbottle (1871-1948)

Harbottle attended Gakushuin University from 1883-1888.

From 1887-1888 he was a classmate of Prince Yoshihito, who later became Emperor Taisho.

Emperor Taisho (1879-1926; ruled Japan from 1912 to 1926)

In 1887, a group of haole businessmen, with support from a contingent of US Marines, took control of the government of Hawai’i and presented Kalakaua with a new constitution restricting his powers. The students in the king’s study abroad program were summoned home the next year. Kalakaua died in 1891 while on a rest trip to San Francisco, California. Two years later, in 1893, the haole faction forced the abdication of Kalakaua’s sister, Lili’uokalani, who had succeeded him as the ruling monarch and who had drafted a new constitution aimed at restoring the Hawaiian monarchy’s power and authority to govern the kingdom.

Japanese Immigration to Hawai'i, 1868-1924

One outcome of Kalakaua’s 1881 visit to Japan was an agreement between the Hawaiian and Japanese governments in 1885 to allow Japanese immigrant laborers to travel to Hawai’i for plantation work. Although an earlier group of Japanese immigrant workers had arrived in 1868, for 17 years thereafter, the Meiji government prohibited emigration of workers due to reports that workers were treated harshly. For nine years after the 1885 agreement, twenty-nine Japanese government-sponsored groups were sent to Hawai’i before the agreement was terminated in 1894. However, private labor contractors continued to bring Japanese workers to Hawaii’i until 1924, when immigration from Japan was banned by the U.S. government, which controlled Hawai’i as a Territory. The ban was based on fears that the increasing Japanese population in Hawai’i and on the West Coast of America would threaten American political control.

Despite the long hours, the low pay, the hard work, and the harsh conditions of plantation life, many of the Issei stayed on in Hawai'i rather than return to Japan.

They began to raise families. (Bachelor workers sent for brides from their homeland; others brought their wives with them.) Both men and women worked on plantations, contributing to the great wealth produced by the sugar industry.

"By the 1930s, Japanese immigrants, their children, and grandchildren had set down deep roots in Hawaii" (See “Hawaii: Life in a Plantation Society,” at the Library of Congress website.)

The Nisei (second generation of Japanese abroad) grew up in a bicultural environment; they were taught to respect their ancestors and ancestral culture and attended Japanese language schools and Buddhist temples; at the same time, they were U.S. citizens educated in American schools. When the war between Japan and America broke out in 1941, many Nisei volunteered for U.S. military service and distinguished themselves for bravery and loyalty to America. (See the Go For Broke National Education Center for information about the service of Nisei soldiers in the100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the Military Intelligence Service.)

Before, during and after the war, the Issei and their descendents moved from the plantation and into the economy of the multiethnic society that was developing in the islands. They worked with and among other ethnic groups, including Hawaiians, Whites, Chinese, Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, and Koreans to contribute to the political, economic, social, and cultural life of a multicultural community. In Recollections (1993), Hawaiian writer John Dominis Holt captures the rich, vibrant world of multicultural Honolulu in the first half of the twentieth century:

As I recall Hawai'i before statehood, computers, and nuclear warheads, it was a world of great eating and drinking bouts, flavored by the introduction of customs and habits of the diverse peoples who came to settle in Hawai'i. The exotic foods of Asia, Europe, and America and the salty, fatty cuisine that became labeled as Hawaiian were eaten by all. The old fish market downtown flourished with foods of all kinds and became a sort of esplanade, a gathering place, for both fashionable and ordinary people alike. Everyone went to market, not only to shop, but to meet friends.

The Chinese gave great dinners of stuffed oysters, shrimp Cantonese, egg rolls, broiled squab, hum hah pork, lop cheong, sweet-sour cabbage and meat, kau yuk, and many other delicacies.

The Hawaiians celebrated by giving lu'au, replete with kalua pua'a (pig cooked in an imu, or underground oven), various types of raw fish and limu (seaweed), chicken or squid fixed with taro leaves and coconut milk, and sweet potatoes. The feast was topped off with rich, custard-filled cream cakes and washed down with soda pop of all flavors. The tables were decorated with fern leaves, hibiscus flowers, bananas, papayas, breadfruit, and mangoes.

The Portuguese cooked great pieces of pickled pork. They produced marvelous breads and a tasty doughnut called malasadas for feast days and Holy Ghost celebrations.

The Japanese, at New Year’s, would spend a half-year’s wages on wonderfully decorative and imaginative delicacies. Sweet rice-paste cakes called mochi were filled with a black bean mixture called black sugar. Fish was prepared in the most stylish and incredible ways; a simulated net carved from a great turnip would cover a whole fish. This splendid display would be given a final embellishment of flower-like decorations carved from carrots and radishes.

The Puerto Rican people feasted on cundudis, pigeon peas and rice, and pateles made with mashed green bananas that served the purpose of corn meal in a tamale. They also served deliciously flavored roasted bits of beef or pork.

At wedding celebrations, the Filipino people roasted whole pigs over a spit and prepared a strongly spiced dish made from chicken or pork, called adobo. It was a marvelous sight to come upon a little house in the cane field camps of the sugar plantations and find the golden-crusted carcass of a hog being patiently turned on a spit over hot coals. It was even more rewarding to stay and be offered bits of the barbecued pork, especially the skin, roasted crisp with the consistency of peanut brittle.

Holt also remembers of Japanese flower seller who lived in his neighborhood:

The flower lady, Mrs. Yamashita, lived above us in a well-run, attractive house. A widow, she grew flowers with the help of her sons—pleasant, likeable, young men, who all graduated from the University of Hawai'i. Mrs. Yamashita arrived carrying her basket and wearing a large hat. She grew mainly African daisies, fragrant carnations, and varieties of chrysanthemums. Always, Mummah bought several bunches of African daisies, which sat giddy and delicate, in a cut-glass vase on the dining room table. Carnations went into another cut-glass vase to sit on a pedestal of koa. Chrysanthemums, when we could afford them, went into a squarish Chinese vase and were placed on one of the remaining tall, thin Chinese plant stands. Mrs. Yamashita was all business, telling us only the briefest details of how her sons and one daughter were faring at school.

(See “Sacred Forests” for J.D. Holt's role in the story of Hawai‘iloa, the voyaging canoe.)

Hokule'a's navigator, Nainoa Thompson, remembers the learning he received from Yoshio Kawano, the milkman, while growing up in the 1950's in Niu Valley:

Nainoa grew up on his grandfather's dairy and chicken farm in Niu Valley-when the valley was still all country. It was Yoshio Kawano, the milkman, who introduced the ocean to Nainoa. Dawn would often find Nainoa sitting on Yoshi's doorstep, waiting for Yoshi to take him fishing. Yoshi would bundle Nainoa into the old car, and off they'd go to fish in the streams or on the reefs. He came to be at home with the ocean, feeling the wind, the rain, the spray against his body. To the five-year-old Nainoa, the ocean was huge, wild, free, and open. The ocean and the wind were always changing; this was so different from the serenity of the mountains and the farm. Nainoa came to sense and feel the tune of the ocean world, develop-ing a personal relationship with the sea. These early experiences, Nainoa thinks, were an essential preparation for becoming a navigator: "We learn differently when we are young; our understanding is intuitive and unencumbered."

Nainoa learned from Yoshio; he learned from Dad, from Mom, from Grandma and Grandpa; he learned from those who loved him and showed him kindness. Nainoa thrived.

Cultural Exchanges: Things Hawaiian in Japan

Hula

In the 1960’s as tourism from Japan expanded in Hawai’i, things Hawaiian have grown in popularity in Japan, and things Hawaiian have become a part of Japanese culture. Among two of the most popular aspects of Hawaiian culture transplanted to Japan are hula and Hawaiian music. In 2005, a Honolulu Advertiser article reported that hula halau (schools) are flourishing in Japan and an estimated 300,000-400,000 people were involved in hula. (“Japan hooked on hula,” July 11, 2005).

Japanese Hula Dancers, by Rebecca Breyer, Honolulu Advertiser, July 11, 2005

Hawaiian Music

Hawaiian music has been popular in Japan much longer. Keith and Carmen Haugen point out in “Japan & Hawaiian Music” that “Hawaiian music in Japan dates back to 1881 when a Japanese band played “Hawai‘i Pono‘i” at Yokohama Harbor, to welcome … King David Kalakaua. Hawaiian music was performed at the Yokohama World’s Fair in 1923 and was adopted by some musicians in Japan. In the 1930’s, Hawaiian musicians toured Japan. After the disruptions created by World War II, the popularity of Hawaiian music resumed and continues today. There are musicians and clubs dedicated solely to playing Hawaiian music. In the 1970’s, with the revival of Hawaiian music in Hawai‘i led by slack key artists like Gabby Pahinui, slack-key (as opposed to the earlier steel-guitar based music) also became popular in the Japanese musical scene.

Hawaiian Songbook, from "Japan & Hawaiian Music."

Surfing

Driving along the coast in Kumano in the summer of 2004, I was surprised to see small crowds of surfers offshore wherever there were breakers. Surfing has spread to the coastal areas of Japan blessed with waves, not just in the southern semi-tropical islands of Okinawa, Kyushu, and Shikoku, but Honshu as well, and even Hokkaido. Some favorite spots on Honshu include Atsumi Peninsula in Aichi Prefecture, Chiba, and Shonan in Kanagawa. The surf isn't at the same level of quality or size as in Hawai'i, but surfers everywhere make the best of what they are given. The best surf is generated by typhoons in the southwestern Pacific during the summer months, when the weather is also hot and the water warm. Surf Japan.com has descriptions of breaks as well as some travel tips. The Outside Japan website hosts a surf columnist, albeit an Australian, not a local (no doubt because the column is written for those who read English).

Surf at Atsumi, from “Atsumi Peninsula Surf Beaches.”

Voyaging

Before passing away in 2005, Tiger Espere, a crew member of Hokule'a, top big-wave rider, and expert fisherman from Hawai'i, spent time in Japan teaching Hawaiian culture in Kamakura, Japan and verifying “the ancestral connection between Japan's pre-Buddhist settlers and native Hawaiians” (a mission given to him by Tahitian elders). He established the Japan-Hawaiian Voyaging Society and was planning to build a voyaging canoe to reconnect the two cultures.

Tiger Espere, Steering Hokule'a, Mokokai' Channel. Hawai'iloa to starboard.

Thing Japanese in Hawai'i

As the Japanese immigrants and their descendants became a integral part of the modern culture of Hawai’i in the 20th century, things Japanese became part of the multicultural landscape of Hawai'i, culural practices like bon dances, lantern ceremonies, and New Year’s mochi pounding, and foods like sashimi, tempura, musubi (rice balls, wrapped in dried seaweed) and shave ice. The Hawaiian writer John Dominis Holt describes in Recollections (1993) a Japanese business household and New Year’s celebration in the multiethnic neighborhood of Kalihi in the early 20th century:

In Kalihi we were plunged into a strange world, multilingual and ethnically diverse. At the other houses where we had lived one never heard the neighbors and rarely saw them; now it was unavoidable for us to see and hear our closest neighbors every day. We came to know extremely well those within an over-all area of six city blocks. Chinese and Japanese families ran the neighborhood stores on King Street and kept small vegetable farms on Kam IV Road. The older members of the Chinese families spoke their native tongue almost exclusively. The great Japanese merchant U. Yamane also had an establishment on King Street. His store was crowded with imports from Japan, canned goods, and pickled vegetables packed in large tubs. I can still see the long radishes colored yellow called takwan being pulled out of their wooden buckets and weighed when purchased. Mr. Yamane was a short, stocky man who came as a merchant with early immigrants from Japan. He was impressive looking, with a short-cropped moustache and short hair. He usually wore grey suits and would remove his coat and tie as the day’s activities progressed. The commodious Yamane home sat facing King Street opposite the family’s variety store. Their yard, the largest in the neighbhood, was filled with fruit trees—mango, avocado, lichee and soursop. Their parties at New Year’s were magnificent affairs where one saw a long, low table groaning with Japanese food specialties. I always marvelled at the boiled or raw carp covered with nets carved from daikon and the Imari platters of sashimi surrounded by “flowers” carved from various vegetables. My father loved those Yamane parties, as the Scotch, bourbon, and sake flowed for most of two days.

“Japanese Traditions” at the Japanese Culture Center of Hawai’i website describes things Japanese in Hawai’i. (The cultural habits and dialects of the immigrants originated in their late 19th and early 20th century rural homelands in Western Honshu, Kyushu and Okinawa; so some local Japanese practices and words that have continued to be used in subsequent generations might strike the young Tokyo traveler today as quaint or curious.)

Intercultural Lives

During decades of interaction and exchange between Hawai'i and Japan, people of Japanese ancestry have become involved in Hawaiian langauge and culture, and people of Hawaiian ancestry involved in Japanese culture.

Patience Namakauahoaokawenaulaokalaniikiikikalaninui Wiggin Bacon

Born on Feb. 10, 1920, in Waimea, Kaua'i, of Japanese ancestry Bacon was orphaned at birth and brought to Honolulu, where she was adopted by Henry and Pa'ahana Wiggin; their daughter, Mary Kawena Pukui, a major 20th century scholar and teacher of Hawaiian language and culture, became Bacon's hanai mother. Bacon learned Hawaiian language, hula, chants, and other aspects of Hawaiian culture from her hanai mother and has spent a lifetime sharing this knowledge through educational programs while serving as a cultural resource specialist at Bishop Museum. The first part of Bacon's Hawaiian middle name means ‘haughty eyes of Kawenaulaokalani’; the second part was given by her grandmother to protect Bacon, connecting her with Pele. (From “The Auntie of Bishop Museum” by Zenaida Serrano, Honolulu Advertiser, August 17, 2005).

In 2004, Bacon was named a Living Treasures of Hawaii in a program sponsored by Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii to celebrate contributions to the islands' cultural heritage. In 2005, the Bishop Museum honored Bacon with the Robert J. Pfeiffer Medal for her dedication to the advancement of Hawai‘i’s cultural heritage, including the language and hula. Bacon was also the recipient of the first Mary Kawena Pukui Award given by the West Honolulu Rotary Club to honor a person not of Hawaiian ancestry who has made a significant contribution to the Hawaiian community through their chosen vocation or field of endeavor. (“Hall of Fame Member, Pat Bacon, Honored By W. Honolulu Rotary Club,” at the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame and Museum website.)

Photo by Deborah Booker, Honolulu Advertiser, August 17, 2005.

Native Hawaiians in Sumo: Jesse Kuhaulua, Chad Rowan, and George Kalima

In the 20th century, three native Hawaiian wrestlers entered and rose through the ranks of sumo, one of the most traditional of Japanese sport. The first was Jesse Kuhaulua, who wrestled as Takamiyama:

“Jesse Kuhaulua was born in Happy Valley, Maui, Hawaii in June 1944 to a Hawaiian father and a Japanese mother. In 1964, at the age of nineteen, Kuhaulua left Hawaii for Tokyo, and became the first American to enter the world of professional Japanese sumo. In March of 1964, Kuhaulua made his debut under the name of Takamiyama and began what would be a twenty year career. In 1968, Takamiyama was promoted to the Makuuchi division representing the highest level of Japanese sumo. Before his career was over, Takamiyama achieved the rank of sekiwake, the third highest in sumo, and established records for most consecutive tournaments (97) and most consecutive bouts (1425). The highlight of his career occurred in 1972, when he defeated Champion Asahikuni to win the Emperor’s cup and become the first foreign-born sumotori to win a championship. Upon his victory, a Japanese ambassador read a congratulatory message from President Richard Nixon, marking the first time that English words were spoken to a Japanese sumo audience.”(From the biography of Takamiyama at the American Sumo Association website; see also “Takamiyama one of sumo’s iron men,” by Ben Henry, Honolulu Star Bulletin, October 6, 1999); and "Jesse Kuhaulua" by Ferd Lewis Honolulu Advertiser, July 2, 2006).

Takamiyama’s success paved the way for other wrestlers from Hawai’i to enter sumo, including Saleva’a Atisanoe, of Samoan ancestry, who wrestled as Konishiki and who achieved the rank of Ozeki in 1987; native Hawaiian Chad Rowan, who wrestled as Akebono and who in January 1993, after a mere 30 matches, became the first foreigner to attain sumo’s highest rank of Yokozuna, the sixty-fourth grand champion in sumo history (see "Akebono" by Ferd Lewis Honolulu Advertiser, July 2, 2006); native Hawaiian George Kalima, who wrestled as Yamato and attained the rank of Maegashira in 1997; and Fiamalu Penitani, of Samoan-Tongan ancestry, who wrestled as Musashimaru and who became a sixty-seventh Yokozuna in 1999. “The Last Sumotori” by Ferd Lewis provides an overview of the achievements of sumo wrestlers from Hawai'i (Honolulu Advertiser, Saturday, October 2, 2004).

Sekiwake Takamiyama / Yokozuna Akebono /Maegashira Yamato

Photos from the American Sumo Association website

Esther “Kiki” Takakura Mookini

In 2006, author, researcher, translator and teacher Esther “Kiki” Takakura Mookini received the Mary Kawena Pukui Award from the West Honolulu Rotary Club, given to honor a non-Hawaiian person who has made a significant contribution to the Hawaiian community through their chosen vocation or field of endeavor. (“Rotary to honor historian,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 2, 2006).

Aunty Kiki was born in Pa’ia Maui, in 1924. Of Japanese ancestry, she married Edwin Mookini, who served as Chancellor of the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo (1975–1978). Kiki taught Hawaiian history and language at Kapi‘olani Community College and has translated several literary and historical texts from Hawaiian into English. In the 1990’s, her great love for Hawaiian culture led her to become involved with the voyaging canoe Hokule‘a as an educational consultant, crew member, and volunteer in the building of Hawai‘iloa.

In 2005, she was the first recipient of the Pa‘a Mo‘olelo Award from the Hawaiian Historical Society: “Mookini’s contributions to Hawaiian culture include service as a teacher and as a translator. In particular, her translations of historically significant works have made available bilingual texts for students and the general public. They include books such as Anatomia, 1838; various Hawaiian legends such as The Wind Gourd of La‘amaomao; and documents such as District Court Minutebooks. Her contributions to a variety of reference resources, including the Hawaiian Language Dictionary, Place Names of Hawaii, and The Hawaiian Newspapers have aided countless researchers and students.” (From “The Pa‘a Mo’olelo Award: Esther T. ‘Kiki’ Mookini Receives the First Award.”

Photo of Aunty "Kiki" from “Rotary to honor historian,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 2, 2006.

Yosihiko H. Sinoto

Archaeologist Yosihiko H. Sinoto has contributed greatly to our knowledge of the Polynesian roots of Hawaiian culture. Born in Japan in 1925, the son of a plant geneticist, Sinoto developed an early interest in archaeology while collecting artifacts from a prehistoric village site near his school outside of Tokyo. Sinoto left Japan in 1954, planning to study American Indian paleolithic culture at the University of California-Berkeley. On the way, he took a detour to South Point on the Big Island where the Hawaiian and Pacific anthropologist Kenneth Emory was digging at an archaeological site. Emory recognized Sinoto’s training and skill in archaeology and persuaded him to stay on to help. Dr. Sinoto agreed to remain for a semester, which turned into a lifetime.

Dr. Sinoto is currently Senior Archeologist in the Hawaiian and Pacific Studies Department at the Bishop Museum. He is noted for his development of a fishhook chronology to date Polynesian archaeological sites. He has worked throughout Polynesia. His most remarkable discovery, on the grounds of the Bali Hai Hotel on the island of Huahine (see photo right), was the only remnants of an ancient voyaging canoe ever found—wooden planks and parts of a steering paddle and mast—buried in wet sand and preserved. The steering paddle suggests that the original one was about the same size and shape as the paddle developed in modern times to steer Hokule‘a. Sinoto has also worked on restorations of ancient sites, including a remarkable village of chiefs situated in an area called Maeva on Huahine.

Dr. Sinoto received the Robert J. Pfeiffer Medal from the Bishop Museum in 2006, for dedication to the advancement and perpetuation of Hawai'i's cultural heritage. He has also been honored with a Tahitian knighthood for his contributions to Tahitian archaelogy and resotration; and a membership in Japan's Order of the Rising Sun for his lifetime contributions to Polynesian prehistory.

Dr. Sinoto on Huahine, excavating the mast of an ancient voyaging canoe; from “Devoted to making discoveries,” by Mary Kaye Ritz, Honolulu Advertiser, Sunday, April 9, 2006.

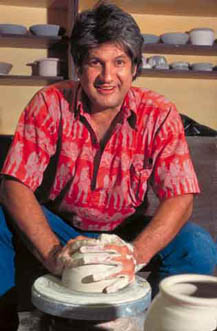

Kauka de Silva

Kauka de Silva, born in Hilo, Hawai'i, is a native Hawaiian ceramic artist and sculptor, who studied his art at Pratt Institute, University of Redlands, and Waseda University (Japan), as well as in Aizu Wakamatsu, Japan, under master mingei potter Takita, who was a student of Hamada Shoji and "classmate" of Shimaoka. Mingei pottery is "people’s art"; "mingei" refers to traditional craft objects made for daily use and enjoyment. Mingei involves years of training and intensive study. Local clays are used to make pottery that is intended for everyday use. Glazes are earthy and matte, colors are natural, such as indigo blue, rust red, forest green and chestnut brown. It is said that the simplicity of the design gives mingei pottery its true beauty. At the same time Kauka's clay works express his Hawaiian ancestry and the Hawaiian environment through their motifs, colors, and forms.

His work has been widely exhibited locally, nationally and internationally in places such as the Mingei-kan (Mingei Museum), the St. Louis Museum, the Stuttgart National Museum, the Honolulu Academy of Arts, Renwick Gallery, Parsons Gallery, and the Hawaii State Art Museum. His pots and sculptures are in numerous private and public collections such as The State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, the Mitsukoshi Collection, the Peabody Museum, the Honolulu Academy of Arts, and the Parsons Collection. Kauka’s studio “Huli Honua Pottery” is located in Hau’ula, Oahu.

A professor of art at Kapiolani Community College, Kauka is master teacher as well (Excellence in Teaching Award from the University of Hawai'i system, 2004). Since 1994, he has been passing on his art to student-apprentice Randall Ho.

Kauka de Silva. Photo by Carl Hefner

Jennifer Kehaulani Oyama

Symbolic of the intercultural, multiethnic character of Hawai’i that emerged in the 20th century is Jennifer Kehaulani Oyama. In April 2003, 21 year old Jennifer Kehaulani Oyama, of half Japanese ancestry, mixed with Portuguese, Polish, Irish, Spanish and Hawaiian ancestries, won the Miss Aloha Hula title at the 40th Annual Merrie Monarch Festival in Hilo, considered the premiere hula competition in the world. She is a member of Halau Na Mamo O Pu`uanahulu, led by kumu hula Sonny Ching. She was also in a three-way tie for first place in the Hawaiian language competition after reciting 3 chants. Oyama began dancing hula at age 5 and joined Halau Na Mamo O Pu`uanahulu in 1994.