1978 Voyage To Tahiti Cancelled After Hokule‘a Capsizes

At 6:30 pm on March 16, 1978, Hokule‘a left Ala Wai Harbor in Honolulu on a voyage to Tahiti. The plan was to document a round-trip navigated without instruments and to test traditional lauhala sails and traditionally preserved food.

The captain was Dave Lyman, the first mate Leon Sterling. Norman Pi‘ianai‘a was the instrument navigator (who would record the actual position of the canoe), and Nainoa Thompson the non-instrument navigator who would guide the canoe. Pi'ianai'a would check Nainoa's accuracy with instruments and give him fixes only if Nainoa was dangerously off course.The other crew members were Snake Ah Hee, Eddie Aikau, Charman Akina, Wedemeyer Au, Bruce Blankenfeld, Kikila Hugho, Sam Ka‘ai, John Kruse, Marion Lyman, Buddy McGuire, Curt Sumida, and Tava Taupu – sixteen crew members in all.

According to the Coast Guard report, the canoe left O‘ahu in 30 knot trade winds, with clear skies, 6-8 foot seas from the NNE, and 8-10 foot swells from the NE. A gale warning was in effect that day, but the weather was forecasted to be moderating within 24-36 hours from 8 am. Hokule‘a had sailed in such conditions before; it was, according to Captain Lyman, "the type of weather they were looking for on departure,” to get a fast start to the voyage.

Will Kyselka, in An Ocean in Mind, summarizes what happened as the canoe headed toward Lana‘i for South Point on the Big Island:

Swells were high, but the canoe had ridden out such seas before. However, this time it was heavily laden with food and supplies for a month's journey. The added weight put unusual stress on the canoe, making it difficult to handle. Turning off-wind eased the strain but it also caused the sea to wash in over the gunwales, filling the starboard compartments and depressing the lee hull. Winds pushing on the sails rotated the lighter windward hull around the submerged lee hull, now dead in the water. Five hours after leaving Ala Wai Harbor, Hokule‘a was upside-down in the sea between O‘ahu and Moloka‘i.

All that night [sixteen crew members] clung to the hulls of the stricken vessel, huddling to protect themselves as best they could from wind and wave. Daylight came. Airplanes flew overhead but no one saw Hokule`a. .... Most alarming, though, was the fact that the canoe was drifting away from airline routes, decreasing its chance of being spotted.

Snake Ah Hee left on a surfboard to summon aid. When a low-flying airplane appeared, he assumed that the overturned canoe had been seen, and he returned. After a long period of waiting it became clear that it was not so.

Eddie Aikau wanted to go for help. An expert waterman, he had saved the lives of many swimmers in trouble in the powerful surf of Waimea Bay on the north shore of O‘ahu. Nainoa paddled out with him a short distance to test the surfboard and waves. Eddie would go alone. The crew, clinging to the overturned hulls, watch[ed] in silence as he rode the waves into a fate not unknown to many of the people of old who sailed toward distant lands. (31)

Eddie was never seen again....

It was about midnight when the large wave hit the partially submerged canoe and turned her over. The crew was all accounted for and took shelter on the leeward hull, standing on the running board. Earlier the crew had put on foul weather gear and life jackets and had gathered up supplies. They fired flares to signal passing aircraft, but weren't noticed. The crew wasn’t able to raise anyone on the emergency radio. There was no escort boat accompanying the canoe.

The next morning, March 17, the crew could see the islands of O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, and Lana‘i. The Coast Guard report indicates rhe canoe was drifting to the west at a little under one knot, away from Lana‘i and Moloka‘i and out of the air and sea lanes. Captain Lyman and others were also concerned about the physical condition of some of the crew. Eddie asked twice for permission to paddle on a surfboard to summon help. He was denied. At 10:30 am, however, he was given permission to go. He was directed to head for Moloka‘i and use the current to assist him to Lana‘i. The crew joined hands in a prayer then wished Eddie strength and luck as he departed.

Crew member Kikili Hugho recalls the experience in an interview with Jan Tenbruggencate of the Honolulu Advertiser:

We were like hours away from losing people. Hypothermia, exposure, exhaustion. When [Eddie] paddled away, I really thought he was going to make it and we weren't. That's how bad it was, that we were doomed. (Honolulu Advertiser, March 16, 2008)

At 3:30 pm, a ship passed but did not see the overturned canoe. That night, however, at about 8:47 pm, flares from the canoe were spotted by the last Hawaiian Airlines flight from Kona. The plane circled overhead and flashed its landing lights, then reported the sighting to the U.S. Coast Guard. Hugho told Tenbruggencate:

We were close to dying out there. At 7:15 or 7:30 [pm] we started looking at the Kona direction for the last flight coming out of Kona. The flight left Kona slightly late, and the pilot altered the flight path to compensate. It was a miracle find, a miracle rescue.

Based on the pilot’s report, the Coast Guard dispatched a helicopter, which found the overturned canoe at 9:27 pm, at 20° 53.5 N, 157° 36' W – about 30 miles south of Makapu‘u on O‘ahu, 23 miles southwest of La‘au Point on Moloka‘i and 35 miles west of Keanapapa Point on Lana‘i. It was reported that all crew members except Eddie were still with the canoe. The Coast Guard launched a search and rescue effort immediately, joined later by the Civil Air Patrol, private boats, and a civilian helicopter hired by the Aikau family.

At 1:20 am, on March 18, the Coast Guard cutter Cape Corwin arrived at the overturned Hokule‘a, which had drifted to 20° 53.5 N, 157° 39' W, about two miles to the west of where it was first sighted by the helicopter. It was decided to wait until first light before attempting to right the canoe and tow her back to Honolulu.

At 5:11 am, a strobe light was seen by a Hawaiian Airlines pilot about ten miles SW of Moloka‘i and a Coast Guard C-13 was sent to the spot but did not see the strobe.

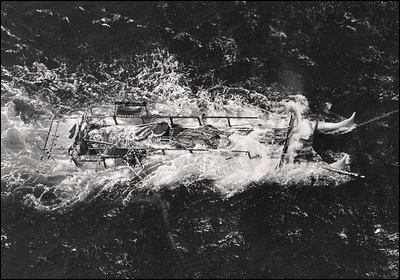

That morning, the canoe was righted and towed to Ke‘ehi Drydock.

Aerial photo of Hokule‘a being towed back to Ke‘ehi. Advertiser Photo Library

At 3:20 pm a civilian helicopter reported seeing Eddie’s surfboard at 20° 47 N, 157° 41' W, about 5.5 miles southwest of where Hokule‘a had been sighted by the Coast Guard helicopter, but the seas were too rough to retrieve the board. The Coast Guard continued its search until March 23.

The loss of a crew member was devastating, but the voyaging community was determined to carry on. Nainoa Thompson reflects:

After Eddie's death, we could have quit. But Eddie had this dream about finding islands the way our ancestors did and if we quit, he wouldn't have his dream fulfilled. Whenever I feel down, I look at the photo of Eddie I have in my living room and I recall his dream. He was a lifeguard ... he guarded life, and he lost his own, trying to guard ours. Eddie cared about others and took care of others. He had great passions. He was my spirit.

He was saying to me, "Raise Hawaiki from the sea." But his tragedy also made us aware of how dangerous our adventure was, how unprepared we were in body, mind, and spirit.

The tragedy brought a heightened concern for safety to the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Henceforth, the canoe would not voyage without an escort boat with which she would maintain regular radio communication. The hatch covers were made watertight. (Chad Baybayan recalls working on Hokule‘a in an Alu Like program, raising the gunwales of the canoe and laminating wood to make a stronger boom.) Finally, safety checklists and procedures were developed, and training programs were made more rigorous; crew safety became the primary concern in preparing the crew for a voyage.