Palmyra Training Voyage (2009)

On March 11, 2009, a new crew of Polynesian wayfinders aboard the Hōkūle‘a – the iconic traditional Hawaiian open-ocean voyaging canoe – set sail for the first time to Palmyra Atoll in the central Pacific. This month-long sail was part of the training for the young navigators, captains and crew members as well as educators and scientists who will take part in the Hōkūle‘a Worldwide Voyage.

At Palmyra, they explored the open ocean, coral reefs and land of this remote and magnificent place. Using the Internet, they interacted with students while on the atoll and brought knowledge and lessons learned back home to Hawai‘i to help all of us navigate our own future.

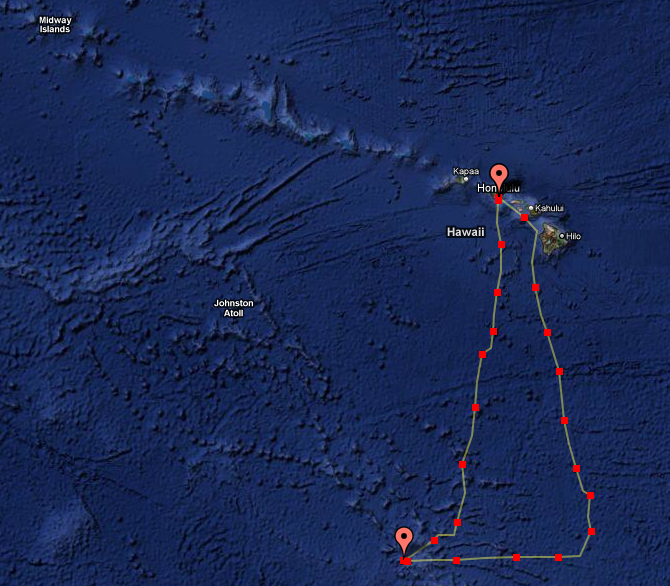

Palmyra Training Voyage. Tracking Map by Michael Shintani. The left track is the voyage down to Palmyra. The right track is the voyage back to Hawai'i.

Palmyra Atoll, located 1,000 miles south of Hawai‘i in the Line Islands, is one of the most spectacular marine wilderness areas on Earth. Its lagoons, coral reefs, and submerged lands support a complex web of life – everything from sharks, sea turtles, manta rays, and giant clams, thousands of exotic fish, to a million nesting seabirds. Palmyra is a National Wildlife Refuge – and recently included in a new National Marine Monument – protected cooperatively by The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. For more about Palmyra, see Palmyra Atoll: A Center of Study (Nature Conservancy website).

The training voyage to Palmyra was the first step in preparation for the most challenging and difficult journey yet of Hōkūle‘a – charting a course circumnavigating the globe.

News Articles

- “Next generation prepares to inherit the Hōkūle'a helm,” by Liza Simon, Ka Wai Ola Loa (Office of Hawaiian Affairs), March 2009.

Next generation prepares to inherit the Hōkūle'a helm

Palmyra, other voyages providing training for future captains

Hōkūle'a is sailing for Palmyra and beyond with a new generation of Native navigators aboard. – Photo: Arna Johnson

"Sand and varnish, sand and varnish. Hold the wood and love the canoe!" With this singsong phrase, Heather Nahaku Kalei laughingly described her introduction to the Hōkūle'a several years ago, when the iconic canoe was dry-docked in Honolulu and she worked on it as part of a class project at the University of Hawai'i. "It was great and I would have been fine if I never got past that," she recalled.

But she did. As you read this, the 23-year-old from Pana'ewa on Hawai'i Island might have already completed a sail on Hōkūle'a to Palmyra Atoll – a wildlife refuge 1,000 miles to the south that was recently included in a new national marine monument protected by The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. While there, Kalei will conduct a scientific census of Palmyra's bird population – an endeavor she will undertake as a UH senior majoring in biological systems engineering.

Kalei, who has sailed the Atlantic Ocean, is thrilled to be aboard the Hōkūle'a, which helped launch the Hawaiian cultural renaissance three decades ago. Referring to Micronesian navigator Mau Piailug, known for mentoring Nainoa Thompson to become Hawai'i's first modern Polynesian navigator, Kalei said: "Mau shared knowledge that was taboo. He broke with tradition because so many came to him searching, hungry to learn. He helped revive more than traditional navigation, because Hōkūle'a is more than a craft. It's a leadership community."

Kalei's remarks are right on course with a new era of Hōkūle'a, embodied in the voyage to Palmyra, which left Sand Island on March 10.

Kaina Holomalia, 24, said the Hōkūle'a builds trust and values among crew members of different backgrounds. 'We live every day to the fullest – not knowing that in a couple of hours you (may) run into a storm you're not going to come out of.' – Photo: Liza Simon

"We need to pass on the tools of leadership, so a new generation can expand Hōkūle'a as a platform not only for navigation skills but also for education, science and aloha," said Bruce Blankenfeld, captain and navigator for the Hawai'i-Palmyra crew.

To pass on the tradition, Hōkūle'a's nonprofit Polynesian Voyaging Society is supporting 12 long-distance training voyages in which 40 percent of the crew must be younger than 30.

The voyaging society hopes to train the new generation of Hōkūle'a sailors to serve as modern ambassadors of mālama 'āina and sustainability and to eventually carry these values around the world in 2012, when Hōkūle'a is slated to begin a circumnavigation of the globe at tropical latitudes.

"For three and half decades, there has been a chain of mentorship allowing more and more people to step up to the experience of the Hōkūle'a," Blankenfeld added. "I personally owe so much to Nainoa Thompson. He started so much of this by sharing his wisdom. Now I'm one of the older guys ready to pass it on. By this, I don't just mean handing out information in a one-way flow. A big piece of traditional navigation is a constant interchange of communication. (With the Palmyra novices), I wait for them to come up with the important questions. And this happens. They have these great a-ha moments of understanding from a place that has true meaning in their experience. ... They are very committed to the vision of the canoe."

Twenty-three-year-old Heather Nahaku Kalei of Pana'ewa says it would be incredible to sail aboard the final leg of Hōkūle'a's planned circumnavigation of the globe – which would allow her to sail into Hawai'i Island as she imagines her ancestors did. – Photo: Liza Simon

Asked if he thought the planned circumnavigation is ambitious, Blankenfeld, said it is but it's also inevitable, given the propensity of those involved with Hōkūle'a to turn big dreams into stunning accomplishments. In the beginning, the dream was to demonstrate that ancient Polynesians traversed even the tiniest coral atolls in the world's largest ocean by developing a system of navigation based on knowledge of stars and other celestial bodies along with wind and wave patterns. Under European domination, the ancient knowledge was not only eclipsed, it was challenged by prevailing opinions that only Western charts and instruments could lead navigators across vast seaways, suggesting that the feat of pan-Pacific settlement was random and accidental.

Palmyra was selected as the first destination, because it lies at the end of a relatively easy southward seaway. It also offers both a scientific research station and an island wilderness similar to the remote environments settled by Polynesian sailors of antiquity, who knew how to thrive on the limited resources the small splits of land offered. In other words, it is a living classroom in the concept of mālama 'āina – or its modern counterpart – sustainable environmental practices.

In 1975, Hōkūle'a – a replica of an ancient sailing canoe, successfully retraced the ancient migration route from Hawai'i to Tahiti, thus beginning a turning back of the tides of erroneous assumptions. The rest is history – or rather a revival of history that has gripped the modern imagination with newfound respect for ancient Polynesian seafaring wisdom.

"In three-and-a-half decades, the Hōkūle'a has logged over 125,000 sea miles with well over 1,000 sailors – some of whom are no longer with us," said Blankenfeld, the captain. "We started raw with guys who were just great sailors. They expanded our skills, but we can always do it better if we keep to the mantra that the Hōkūle'a is all about opportunity for expanding knowledge."

Knowledge from the exploits of the Hōkūle'a, the Hawai'iloa and other ancient canoe replicas has become systemized, making possible the academic courses within the University Hawai'i system, including the Honolulu Community College Marine Education Training Center at Sand Island. Some on the Palmyra voyage have been trained at the center; others are quite green. The common denominator, said Blankenfeld, is that they've demonstrated qualities of kindness, respect and hospitality. With self-deprecating humor, Kalei explains that in lieu of a formal selection process: "They figure out if they can live with you at sea. You work hard, keep your ears open and your mouth closed. Not that anyone is mean to you. Everyone is amazing."

In turn, Blankenfield says of the young sailors: "The new generation has grown up around the vision of the canoe. They've been inspired by it. They grasp life is a voyage: you map it out, find the strength to weather the pitfalls and get past the storms. They also have a lot to teach us."

Captain and navigator Bruce Blankenfeld explains to novice crew members how traditional Polynesian navigators were able to estimate longitude based upon knowledge of currents and other clues from nature. The class took place aboard the Hōkūle'a before it set sail March 10 for Palmyra Atoll, 1,000 miles to the south. – Photo: Liza Simon

Preparing to set sail

On a windy morning in early March, when storm conditions once again trumped a planned departure for Palmyra, Blankenfeld was on the deck of the Hōkūle'a fielding crew members' questions on everything from the rigging of lines to the ancient reckoning of longitude – not an easy matter, it turns out, but still do-able according a system developed by Polynesians. Somewhere in the discussion, he finds a way to reinforce one of his pet themes, professionalism: "If you see anything out of place … make a note in your captain's log in a quiet, humble way, because these are the kind of things we use in the end to remind ourselves how well we did and how much better we can do," he tells the crew.

"Uncle Bruce teaches with aloha. He corrects out of deep love and you never feel bad about yourself," said Kaleo Wong. A master's candidate in Hawaiian language at UH, Wong has sailed on previous PVS journeys. The experience heightened his respect for his Hawaiian ancestors, he said. He admires them for being able to read the sky for signs of storms before departure – not relying on the green light from the National Weather Service, as is done nowadays.

While the ancients may have had it tougher, most would agree that life is as Spartan as it gets aboard the Hōkūle'a. Sleeping spaces are above storage holds and beneath nothing more than canvas cover. There is constant rocking, and for many, seasickness. IPods are permitted but, sorry, no radios or watches are allowed aboard, since time must be inferred – as ancient wayfarers did, by keenly observing signs in the sky. Meals consist of nutritious but little fresh fare, carefully planned by UH nutrition experts. Then there is the daily grind of four-hour watches, when a crew member is responsible for everything from checking the steering to reporting on crew morale. To simulate life in the open ocean, the Palmyra crew spent several months making practice runs to neighbor islands.

"The real challenge is becoming attuned to the open ocean," said Kalei, quoting Hōkūle'a voyaging alumnus Carlos Andrade, who also taught her navigation at UH. "He used to say that on land, we get in our little 'box' cars and drive to our 'box' offices and back to our 'box' homes." Compared to this, voyaging on the open ocean offers a chance to rejuvenate the senses, making the limitations of life on board a small sacrifice to pay.

Captain and navigator Bruce Blankenfeld trains novice crew members in traditional Polynesian navigation. – Photo: Liza Simon

Hōkūle'a has taught hard lessons also, like through 1978 disappearance of Eddie Aikau, who vanished at sea in an attempt to get help for this crew mates, after the Hōkūle'a capsized south of Moloka'i. Safety precautions were bumped up after the tragedy, though for many of the 20-somethings on the Palmyra voyage, Aikau's story holds great resonance and sets the bar for selfless determination that makes traditional seafaring well worth so many challenges.

"When you stay out on the middle of the ocean and not seeing any land you get a sense of how small you are in this big earth and you feel humbled at being at the mercy of nature," said 24-year-old Kaina Holomalia, one of the more experienced crew members on the Honolulu-to-Palmyra journey. "It builds trust and family values. We all from different backgrounds, but we live every day to the fullest – not knowing that in a couple of hours you (may) run into a storm you're not going to come out of."

Holomalia, who also serves as watch captain, grew up in Wai'anae, where he said he gave in to temptations of drugs and dropped out of school in the ninth grade. "But lucky my grandfather them was real deep into fishing, diving for tako," he said. "They make net, patch net, fish. So I learned plenty as a kid. Not like at school with them telling me George Washington was my history."

When the Myron B. Thompson School opened an ocean-focused learning program in conjunction with the Polynesian Voyaging Society, Holomalia said he "jumped on it." Now enrolled in HCC's Marine Education Training Center and employed in a commercial maritime business, Holomalia thanks Hōkūle'a for showing him latitudes that once and for all changed his attitude.

"One lesson Hōkūle'a taught to me is that the ocean connects us. In Yap (after the 2006 Hōkūle'a journey between Japan and Micronesia), the captain said, 'When you guys get back to Hawai'i think of us on the canoe; put your feet in the water and we're just on the other side,' " recalled Holomalia, adding that this also opened his eyes to the need to mālama the ocean. "It makes me mad to see 'ōpala in the water. I go pick it up now."

Kalei, the 23-year-old from Pana'ewa, echoes the sentiments of crew mates when she says Holomalia seems primed to take the helm at some point in the vessel's global jaunt. Kalei might not be ready just yet for a worldwide voyage, but it's crossed her mind how incredible it would be on the final leg to return home Hawai'i Island and bask in the red glow of Kīlauea, as she imagines her ancestors did on their first voyage from Tahiti. She, too, has felt the tug of the mentorship role, since becoming involved with the Hōkūle'a. All those tapped for the training mission have "adopted" elementary school classes, making presentations about the Hōkūle'a vision to youngsters. "The knowledge is being perpetuated," said Kalei, who mentored students at Hālau Kū Māna charter school. "You can see this from the questions kids ask. The kids are so on it.”

- “Hokule'a ready for Palmyra,” by Dan Nakaso, Honolulu Advertiser, February 27, 2009.

The voyaging canoe Hokule'a is scheduled to leave Hawaiian waters tomorrow for Palmyra Atoll, a preliminary step in an ambitious plan to circumnavigate the planet and train the next generation of captains and crews in the ancient ways of Polynesian navigation.

Exactly when Hokule'a sets sail on its eight- to 10-day voyage south across 1,000 miles of open ocean depends on weather conditions, especially the winds.

But its arrival and planned six-day stay at Palmyra Atoll will mark the first arrival by an ocean vessel since then-President George W. Bush designated the atoll one of three new Pacific marine monuments on Jan. 6.

"It's a fascinating place," said Barry Stieglitz of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "I wish we had the opportunity to get everyone there. I believe the crew members of the Hokule'a will be very, very pleased to have an opportunity to go.

"It has an incredible human history: shipwrecks, failed financial ventures, World War II military history and even some murders that have been well known here in Hawai'i."

The arrival of a traditional Hawaiian canoe at Palmyra using ancient navigational techniques will bring together two distinct visions, said Suzanne Case, executive director of The Nature Conservancy of Hawai'i.

"One vision of and for people and learning. ... The other vision of place and nature and wildness and wholeness as it can and should be. The view into our deep past of a great people with the Hokule'a and a great place at Palmyra Atoll allows and creates and renews our vision for the future. Taking these voyages and protecting these places are epic undertakings requiring commitment, compassion and courage. With these visions we'll heal ourselves and our peoples and our places all around the world."

The Palmyra trip is just the first of 12 deep-sea training cruises and sea trials this year designed to test and prepare Hokule'a and its crews-in-training for a potential voyage around the world, which could include the dangers of modern-day pirates.

PREPARING FOR FUTURE

Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, initially rejected the idea of sailing Hokule'a around the world when his late father, former Bishop Estate trustee Myron "Pinky" Thompson, began suggesting it in the early 1990s.

Nainoa Thompson yesterday announced Hokule'a's plan to circumnavigate the planet and train the next generations of captains.

But now, with his 56th birthday approaching on March 11, Nainoa Thompson said it's time for Hokule'a's most ambitious plan ever in its 34-year history, to help heal the environment and train the next generation of navigators and captains.

"I was on the edge of a time when 50 years ago one could — in relative terms — say that Hawai'i's oceans were healthy," Thompson said yesterday. "At the same time one of my great lifelong, so-far regrets is that all I did in the last 50 years was witness the decline and didn't do anything about it.

"If we are a society that is committed to the well-being of children not born, then reversing the trends of degradation of our environment is a priority. It's not an option. It's an obligation to children. Fundamentally, that's why we sail. I don't have much tools. I just have a canoe and some extraordinary people and we'll do what we can."

'YOUNG LEADERSHIP'

Hokule'a will embark on its 37-month, worldwide journey of 31,000 nautical miles and 40 countries only if it can first develop a minimum of 12 crews.

The crews, consisting of 12 people each, will take turns sailing the canoe and no one will be asked to be at sea for longer than 30 days, Thompson said.

"For the well-being of Hokule'a to be able to be a tool for the future, you have to have young leadership," Thompson said. "Us old guys are getting old. ... You need young people to be involved because it's their world."

So 40 percent of the crew members have to be under age 30, Thompson said, such as captain-in-training Kaina Holomalia of Nanakuli.

Kaina Holomalia of Nanakuli is a captain-in-training and will be part of the crew heading to Palmyra Atoll. He is also a prime candidate to become one of six new captains for a planned worldwide voyage.

Holomalia, 24, dropped out of Nanakuli High School in the ninth grade and got tempted by "what Wai'anae is known for," he said.

"Hokule'a saved my life in a lot of ways," Holomalia said. He called Hokule'a "a mother that took care of me in times of need."

Now Holomalia plans to work as a watch captain on the trip to Palmyra Atoll, where he hopes to see for himself what healthy reefs and giant schools of fish look like.

Then, Holomalia dreams of sailing Hokule'a up the Leeward Coast as one of its new captains, to introduce the canoe to hundreds of elementary school children and — perhaps — inspire them as the canoe continues to inspire him.

The Leeward Coast is "where she is much needed," Holomalia said.

Holomalia is a prime candidate to become of one of six new and young captains that will be necessary for a worldwide voyage, Thompson said.

"We need Kaina more than Kaina needs us," Thompson said. "He's an investment in the future."

- “Weather again delays Hokule'a,” by Advertiser Staff, Honolulu Advertiser, March 9, 2009.

First, too much wind and too much rain delayed the launch of the Polynesian voyaging canoe Hokule'a for its 1,000-mile training journey south to Palmyra Atoll.

Then after conditions improved on O'ahu, Hokule'a still remained at its berth at the Marine Education and Training Center on Sand Island yesterday because of too little wind.

"It was really windy for several days," said Pauline Sato, who will be sailing with the 12-member crew. "Now they're seeing a weather pattern that includes a big trough, meaning no wind for 800 miles."

Pauline Sato and Heidi Guth bring lei aboard Hokule'a on the canoe's 34th birthday (March 8).

That would mean no wind for 800 miles of a 1,000-mile trip in a canoe sailing by ancient navigational techniques.

The eight- to 10-day trip to Palmyra is designed as one of a dozen sea trials to test Hokule'a and train new crews for a possible 37-month voyage around the planet.

Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, told the crew yesterday that "this voyage is about training," Sato said. "Waiting for the right wind is part of the training. With the ancient people, if the right wind or weather wasn't there, they didn't go for months."

But the delay gave friends of Hokule'a a chance to celebrate its 34th birthday yesterday with lei, which they draped on its bow and on other parts of the ship, including its wooden male and female ki'i figurines.

Hokule'a is not expected to launch today, either, Sato said.

But tomorrow, she said, could bring "the right wind and the right situation."

- “Finally, Hokulea sets sail on 1,000-mile journey to Palmyra Atoll,” by Advertiser Staff, March 10, 2009.

After 10 days of delays, the voyaging canoe Hokulea was set to embark this afternoon on its 1,000-mile sail to Palmyra Atoll.

Hokulea was expected to sail between 4 and 5.

The canoe had endured delay after delay because of combinations of cloudy, rainy weather and small-craft warnings.

Since Hokulea's navigators sail without instruments, clear skies are essential in setting the canoe's initial course.

The Polynesian Voyaging Society says the month-long sail will train young navigators, captains and crew members as well as educators and scientists who will explore the open ocean and coral reefs surrounding the remote atoll.

Hokulea crew member Eli Witt checked the rigging of the canoe today in preparation for departure to Palmyra Atoll this afternoon. Witt will handle communications during the voyage.

- “Hokulea gets dolphin, manta ray escort into Palmyra,” by Advertiser Staff, March 19, 2009.

The voyaging canoe Hokulea arrived at Palmyra Atoll this morning, nine days and 1,000 miles after setting sail from Honolulu.

Hokulea launched from the Marine Education and Training Center on Sand Island on March 10 to begin its 1,000-mile voyage to Palmyra Atoll.

Hokulea's crew reported being surrounded by about 400 melon headed whales as it approached the atoll and escorted into the atoll's main channel by a pod of dolphins and a school of manta rays.

This voyage was intended to help train a new generation of non-instrument navigators.

Polynesian Voyaging Society lead navigator Nainoa Thompson shared his delight in the crew's success.

"This is an amazing day," Thompson said in a news rlease. "These young people have done wonderfully under really difficult conditions.

"This experience is truly transformational and I know that we are seeing the future not only of PVS, but of our island home."

As the first long distance training mission for Hokulea's scheduled worldwide voyage in 2012, the crew sailed to one of the world's most pristine marine and land environments.

As a part of this training they experienced the true fatigue of open ocean voyaging, the complexity of finding a small speck of land in an endless ocean and the rare chance to visit an environment that holds many lessons about how to better care for the places in which we live.

"One of the most valuable aspects of this training is the actual time on sea," said Palmyra voyage captain and navigator Bruce Blankenfeld. "To put deep-sea mileage … days, even weeks … on the canoe living and functioning as an ocean person in an everyday real setting. Its benefits are incalculable."

"There's been a heightening of our senses and awareness of what's going on around us," said Nahaku Kalei, one of the young voyagers. "From learning about the star lines to sail manipulation and understanding weather and ocean patters, we've learned to adjust."

Meeting the crew on Palmyra will be a second training crew which will navigate a return trip to Hawaii.

- “Hokule'a reaches Palmyra,” by Dan Nakaso, Honolulu Advertiser, March 20, 2009.

An "endless pod of porpoises," schools of manta rays and an estimated 400 melon-headed whales escorted the Polynesian voyaging canoe Hokule'a into the pristine waters of Palmyra Atoll yesterday as its young crew wrapped up a nine-day, 1,000-mile journey south from Honolulu using traditional navigational techniques.

The crew tied the arriving Hokule'a to a mooring in the Palmyra lagoon yesterday. From left: Kaina Holomalia, Keala Kai, Chris Baird, captain/navigator Bruce Blankenfeld and Pauline Sato. The voyage was a training cruise and a new crew will train on the return trip. Photo: Mike Taylor

Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, was back in Honolulu yesterday wrestling with conflicting emotions: Disappointed that he could not enjoy the sight of Palmyra and all its marine life for the first time with his beloved Hokule'a — and proud that the canoe and its crew made the trip without him.

"The Palmyra success is that I'm not there," Thompson said.

He plans to make his first trip to Palmyra tonight by plane, along with the bulk of a new crew that will sail Hokule'a back into Hawai'i waters.

During the one day that he'll be on Palmyra, Thompson plans to dive in the waters of the atoll and expects to see a mass of sea life unimaginable in the main Hawaiian islands.

Then-President George W. Bush on Jan. 6 designated the atoll part of one of three new Pacific marine monuments.

The journey also represents the first deep-water, open-ocean voyage this year to train a new generation of young crews to take Hokule'a around the world on a 37-month voyage.

Sailing to Palmyra. Photo: Mike Taylor

In all, Hokule'a is expected to make a dozen interisland and deep-sea training cruises this year.

"It's hard to train as a navigator just interisland because you can see landmarks pretty easily," said Kamaki Worthington, who sailed to Palmyra and is training to be a captain and navigator. "On this long-distance voyage, it's very different. We hadn't seen land for eight days, but we navigated a straight course.

"This training sail helps fulfill the task set out for the worldwide voyage, training young leaders."

Hokule'a captain Bruce Blankenfeld called the performance of the 12-person crew "stellar."

"This is an excellent sign for the worldwide voyage because we have a vision for young leadership and they are stepping forward in an awesome way," Blankenfeld said.

The new crew plans to leave Palmyra on Tuesday on Hokule'a for the return trip, Thompson said, and the canoe will first be towed 350 to 400 miles east to escape the doldrums surrounding the atoll.

It will then take another three to four days to properly position Hokule'a for the estimated 11-day return trip to Honolulu.

- “Hokulea crew enjoying Palmyra Atoll's beauty ... and amenities,” by Advertiser Staff, Honolulu Advertiser, March 20, 2009.

The sun sets on Hokulea and the escort boat Kama Hele, rear, anchored at Palmyra Atoll yesterday. "Pristine, unspoiled, Eden," a crew member blogged today.

Nainoa Thompson and the relief crew that will sail the voyaging canoe Hokulea back to Honolulu arrived at Palmyra Atoll today.

The return trip, like the initial 1,000-mile voyage to Palmyra, will serve as hands-on instruction for a new generation of Hokulea mariners.

Hokulea is scheduled to leave Palmyra on Tuesday for what is expected to be an 11-day trip home.

For now, the crew that sailed Hokulea to Palmyra without instruments is soaking in the beauty of the atoll — and making the most of its amenities.

"... Cannot tear myself away from this Paradise for more than a moment," Mike Taylor wrote in his blog for the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

"Pristine, unspoiled, Eden, what can I say? Comfortable beds, hot showers, toilet without hanging over the side, scrumptuous buffets, no cell phones ... you get the picture.

"The (host) nature Conservancy is spoiling us with snorkel outings, nature walks, etc."

- “Palmyra voyage connects the dots,” by Michael Tsai, Honolulu Advertiser, March 23, 2009.

There's no telling what sort of assumed truths may suddenly become self-evident when you're at the helm of a voyaging canoe in the middle of the Pacific.

For 31-year-old Kaimuki resident Angela Fa'anunu, it was this: The world is round.

Fa'anunu was one of a dozen crew members who guided the voyaging canoe's Hokule'a on its 1,000-mile journey south to Palmyra Atoll last week.

After flying back to Honolulu on Saturday, she and fellow crew members Pauline Sato and Nahaku Kalei spent yesterday afternoon at Maunalua Bay reflecting on what was for each a life-changing experience.

"There was one night when I looked out and it was the clearest sky I had ever seen," Fa'anunu said. "I could see all the different constellations — Aries, Taurus, Gemini. I could see the path of the sun and the moon. That night was a learning experience because it brought everything together."

And as she watched the stars slowly change positions over the course of her watch, all those lessons she studiously noted in her tablet back home in Tonga suddenly clarified in the night sky.

"I realized, 'Wow, the Earth really is round,' " Fa'anunu said, laughing. "You can study and read books, but when you're immersed in an experience like that, you understand the truth of it in a really intimate way."

That night crystallized many truths for Fa'anunu. She thought about the ancient Hawaiians who understood the stars, winds and tides as never-ending narratives that, for those who cared to pay attention, made sense of the world and how to traverse it. And she thought about her teachers at the Polynesian Voyaging Society who reclaimed that knowledge for future generations.

Fa'anunu, a graduate fellow studying urban and regional planning through the East-West Center, said she hopes to take what she's learned back to her native Tonga to help children there better appreciate their world and to accept responsibility for its stewardship.

For Kalei, 23, the experience of visiting a pristine Pacific island environment was equally eye-opening.

"Hawai'i is beautiful, but it's not the same," she said. "Everything was alive. There were huge ulua and sharks right at the water's edge, plus tons of birds and coconut crabs. It makes you realize that Hawai'i must have been like that, and if we just leave it alone, it'll come back."

Nahaku Kalei, 23, was thrilled to get up close with nature during Hokulea's voyage to Palmyra Atoll. "Everything was alive. There were huge ulua and sharks right at the water's edge, plus tons of birds and coconut crabs," she said.

That sort of awareness is encouraging to Hawai'i Nature Conservancy outreach coordinator Pauline Sato, 45, who has worked with the Pacific Voyaging Society for 15 years and was a part of the Palmyra crew.

"Seeing the canoe in the lagoon dock so peaceful, that's how it's supposed to be," she said. "For the whole (upcoming) worldwide voyage mission, we want to connect these special places and bring them back so people will understand that we can't lose places like this.

"But it's not just about somewhere else," Sato said. "It's also about where you live, how you're impacting it, and how you can do better. We can talk about how much fun we had, and that's all true, but if it doesn't change anything here then I don't think we've accomplished what we set out to do."

- “Hokulea drenched on first night of return trip,” by Advertiser Staff, Honolulu Advertiser, March 24, 2009.

Hokulea's crew reports all is well, although very wet, after the first day of the voyaging canoe's sail from Palmyra Atoll to Honolulu, according to today's morning report from the escort boat Kama Hele.

"In general, the evening passed rather free of any real pilikia, but the weather has turned cool, rainy typically doldremic state," the report said. "Just after last night's sunset report the seas appeared to be getting milder. However, as the evening progressed the weather turned sour.

"At 2230 hours, we sustained about a 15 minute deluge with 30 knot winds, with heavy rain and were taking green water over the bow. At that time, Hokulea requested a reduction in speed and a small course change to limit vessel diving into the oncoming swells. At 2340 hours, we received another front, which soaked everything with high winds and pelting rain. This also lasted 15 minutes. By 0030 hours, the midnight watch reported some lightning for about 30 minutes."

The report concludes: "No reason to be alarmed, all is well, looking forward to another lovely day at sea."

- “Hokule'a back from Palmyra,” by John Windrow, Honolulu Advertiser, April 6, 2009.

The Polynesian voyaging canoe Hokule'a returned home to O'ahu yesterday after its voyage to Palmyra Atoll.

Bruce Blankenfeld and (left to right) Capt. Russell Amimoto, Robert Frankel, Zack Keenan, Mike Taylor and Kealoha Hoe bring the Polnesian voyaging canoe Hokule'a back home at Sand Island.

On calm waters under blue skies, Capt. Russell Amimoto's crew of 12 brought the canoe in to a waiting crowd of family, friends and old salts at Sand Island.

One of the saltier ones on hand was Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. He said that storms and overcast skies had been a big problem for the 12-day, 1,400-mile return leg of the voyage, but Amimoto and navigator Bruce Blankenfeld showed great skill and leadership in bringing the canoe home from Palmyra. The vessel had departed O'ahu for Palmyra on March 10 with a different crew, which flew back ahead of Hokule'a.

With the return crew, Thompson said, "The bad weather never let up until a day before they got here." He said Hokule'a and its crew dealt with thunderstorms, squalls and winds of 25 to 30 knots. Plus the skies were overcast most of the time, making navigation extremely difficult.

"They had to read the waves and make hundreds of leadership decisions every day and they had to be good ones," he said.

The trip to Palmyra was part of the Polynesian Voyaging Society's plans for an around-the-world voyage for Hokule'a beginning in 2012.

For that effort, Thompson said, the Polynesian Voyaging Society needs some new captains, and Amimoto will be one of them. "He officially graduates and becomes a deep-sea voyage captain today," Thompson said. "The key factor is leadership and he showed it."

The crew, back home safely, stood in a circle on the deck of the 62-foot vessel and said a prayer. Then the crew members stepped onto the pier to cheers and lei.

Amimoto's wife, Karin, threw her arms around her voyager and gave him a kiss that lasted longer than most. Someone remarked that she kissed him as if they had been apart for years, not weeks. Karin smiled shyly and said, "You have to make every day count."

Amimoto, whose brother, Carey, was aboard the escort vessel, greeted his parents, Carey and Suzanne. He was modest and soft-spoken and said the weather had been a problem, but "not so bad."

They used waves, birds, fish and the sun to guide them, he said, and the stars whenever the skies cleared — "a little of everything."

It felt good to be home, he said, after his first long voyage, which "definitely was an opportunity and a responsibility."

Amimoto credited "lots of good people" for the voyage's success.

His dad told him that he had some Heinekens in a cooler and Amimoto said, "that sounds good."

Crew member Kaina Holomalia, 24, of Wai'anae, said the trip had provided "lots of good (memories) of young people making dreams."

He described being out on the middle of the boundless Pacific in such a small craft as "humbling."

Holomalia said that "when we stepped on the pier today we were doing it for the ones who sailed before and the ones who will sail after. Thousands helped us get here," he said, "not just the 12 you see today."

The Polynesian Voyaging Society plans more deep-sea voyages this year, probably to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands; dry dock and repairs in 2010; sailing to more than 40 communities state- wide in 2011; and commencement of worldwide voyages in 2012.

YouTube Video of the 2009 Palmyra Training Sail

Hōkūle'a: Leaving for Palmyra