The Voyage to Rapa Nui / 1999-2000

Cat Fuller's Journal / Leg 2: Nukuhiva to Mangareva

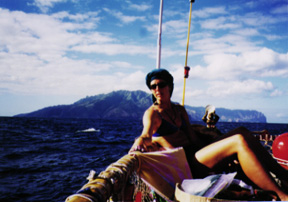

Photo Below: Cat Fuller on the navigator's platform on Hokule'a; Fatu Hiva in the background.

(NOTE: On June 15, 1999,

Hokule'a left Hawai'i on her

sixth

voyage to the South Pacific. Her mission: to sail to Rapa Nui, the most

remote island in Polynesia. Before targeting Rapa Nui from Mangareva, Hokule'a

sailed from Hawai'i to the Marquesas Islands (June 15-July 13), and from

the Marquesas to Mangareva (August 3-August 29). In the following journal

entries from the second leg, Catherine Fuller shares thoughts on her rite

of passage as an apprentice navigator, along with reflections on the bonding

of the crew, voyaging values, and cultural insights, as Hokule'a made landfall

on eight islands-the six major islands of the Marquesas, Pitcairn, and Mangareva.

(NOTE: On June 15, 1999,

Hokule'a left Hawai'i on her

sixth

voyage to the South Pacific. Her mission: to sail to Rapa Nui, the most

remote island in Polynesia. Before targeting Rapa Nui from Mangareva, Hokule'a

sailed from Hawai'i to the Marquesas Islands (June 15-July 13), and from

the Marquesas to Mangareva (August 3-August 29). In the following journal

entries from the second leg, Catherine Fuller shares thoughts on her rite

of passage as an apprentice navigator, along with reflections on the bonding

of the crew, voyaging values, and cultural insights, as Hokule'a made landfall

on eight islands-the six major islands of the Marquesas, Pitcairn, and Mangareva.

Catherine Fuller, a 32-year-old University of Hawaii graduate student in anthropology, began working with Hokule'a and her sister canoe Hawai'iloa in 1993, under the guidance of Wright Bowman, Jr. She has been active in all aspects of the voyaging-repairs and maintenance of canoes, training novice crew, inter-island and open ocean sailing (1995 and 1999), navigation, and school and community presentations. She is also on the board of directors of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Her journal entries were published in The Honolulu Advertiser between July and September 1999.)

July 26, 1999: We're on the plane to Nuku Hiva at last. The last week in Tahiti's been good for Moana (Doi, the other assistant navigator) and me. We had time to study and settle ourselves. Now, on the plane with the majority of the crew, I'm beginning to have a awareness of all these personalities as a CREW, as one team.

August 2: Our last night here in Taioha'e. We've had time to get to know the rest of the crew, and reacquaint ourselves with Hokule'a. More importantly, though, we've had the time to make good friends here. Taioha'e is a beautiful place: a large bay embraced by green mountain ridges reaching to the sea. In the mornings, a light smoky haze from rubbish fires catches the early light, giving the mountains a feeling of untouchability. Here, Tava (Taupu Teikihe'epo, a crew member originally from the Marquesas) was in his element, as this is his home. He sat down with me one night to tell me about the names of the islands and what they mean. The island names all refer to the parts of a house; together, the islands are a whole, as a house is. The name Taioha'e refers to the completed house. The name Nuku Hiva, our first island, refers to the gathering of people, filling the valleys from the shore to the peaks of the mountains. Here, we came together as a crew.

August 3: Ua Pou, like Nuku Hiva, is a place I had visited previously, in 1995 with Hokule'a and Hawai'iloa. The short voyage there was our first sail as a crew: a promise of what was yet to come. We were treated to our first Marquesan dancing. Where Tahitian rhythms recall torchlight on the ocean, Marquesan drums are the thunder of the puaka (pig) in the forest, and the soaring of the tropic birds in the skies above us. We went on a tour of Hakahau, our anchorage, and the neighboring valley. Ua Pou's silhouette, from a distance, is unique in the world. Its rock spires seem too beautiful and otherworldly to be real ... a magic castle with hidden gems of huge, ancient marae, lush valleys, beaches with surf and soaring cliffs. On this first part of the trip, we came together to put up the "supports" of our "house"-to-be. Ua Pou refers to the poles supporting a house.

August 4: We landed at Hane, on the island of Ua Huka. As the sun rose, we had our first sight of great rocky cliffs standing vigilant over the clear blue bays. Touring the island, we found the barren, Makapu'u-like coast hid an impossibly deep and impossibly green valley. Only 600 people live on this island, in four villages nestled together on a small stretch of the south coast. Imagine exploring the rest of the island! Coming here was our second sail together: routines and drills have become smoother and more familiar, and the bonds of friendship are rapidly forming. Ua Huka is named for the lashings which bind the parts of a house together.

August 5: An overnight sail to Tahuata. It's my first experience solo navigating, for four hours, anyway. I'm totally nervous. It's an awesome responsibility the navigator has, to hold the fate of others in your hands. The winds are light, so even though I kept the line, we were pushed to the west. Tahuata is a paradise of coconut trees bathed in golden light. We anchored in Vaitahu, in water bluer than a postcard picture. Our greeting in Vaitahu was as warm as the hearth for which the island is named. We are eating our way through the islands, and Vaitahu was a prime example. Fresh fish and crab, po'e and poisson cru to our heart's (and stomach's) content. We visited the next village, Hapatoni, by boat, as there are no roads in. Even the dolphins in the bay greeted us with friendly smiles. As we left the island, we passed by Hapatoni to show them the canoe. As Maka, Kealoha and Kaniela announced our arrival to the madly-waving residents, our new friends, the mountains echoed our pu, or conch shell, in a harmony that brought us to silence.

August 7: Hanavave on Fatu Hiva: the first impression as you enter the bay is that of having been transported to a lost time and place. Rock cliffs and towers stand guard over the encircled bay, and beckon you into the valley beyond. What do you do when each island is more beautiful than the last? Although I still wake up in the night feeling homesick, this is a paradise come true. We hiked through a valley to swim in skin-chilling water at the base of a waterfall. Behind us, the ridgeline stretched across the sky, embracing us in jungle green. As a crew, we've now outfitted our canoe for comfort: new toilets, windblocks in the navigator's platforms, and other assorted personal touches. The canoe is a home now; more than that, she is our mother and we the children she nurtures. Fatu Hiva is named for the rafters of the house, which hold up the roof, offering protection to those inside.

August 8: Hiva 'Oa at last. Our first night here, and a return to modernity for us. It's a bit of a shock to be in civilization again, after a week of island paradises and small villages, but this is necessary. Here we make the final preparations for the long leg to Mangareva. We endured our first squall as a crew; cold, wet and totally exhilarating. We are awaiting the arrival of our food and supplies for the rest of the journey, and then we plan to head out on the open sea. Here we are, where the cliffs catch the clouds . . . Hiva 'Oa, the ridgepole of the house. We are a family now, having built our house through this last week, soon to be our own little island in the deep blue sea.

August 10: Hiva 'Oa-We spent today packing our food for the open-ocean segment of the voyage and for our layover food in Mangareva-30 days worth in 113 boxes. We took all the food to a house and laid it out in the garage, so we could then pack the meals for each day. Looking at all the food laying out made me realize what an excess we have. (No criticsm intended of Mary Fern and Lita Blankenfeld, who were extraordinary at planning, purchasing, packing and shipping all the voyage food!) We have more food in this garage than the stores in Hanavave (Fatu Hiva) and Vaitahu (Tahuata) did combined.

That tells me something about how much we have at home, and how much of it we take for granted. The most striking aspect of our trip through the islands, besides the geography, was the aloha and the generosity of the people. We were fed like royalty at each stop; a combined effort of each village to feed 23 people. We ate crab, chicken, pork, beef, fish of all kinds, taro, ulu, fresh fruit and po'e. And of course, the ever present pamplemousse, or grapefruit. Without knowing us, these people opened their homes and their hearts. We've never eaten so well on a voyage before.

It's almost embarrassing to think of the comfort most of us are accustomed to at home, as compared to the simplicity we find here. They give us so much with so little thought of themselves; when I look at what fifteen people will be eating over the next three weeks, I realize the amount they give, and the love they give with it. I'm not saying the people who have taken care of us are poor; they are rich in ways most people have forgotten. They have beautiful islands where they can be self-sustaining. They have fish, fresh water, pigs, chickens, ulu and taro, and no need for TV or radio.

On the canoe, because space is so limited, simplicity is key. Personal gear is limited to (what will fit in) a 48-quart cooler. In the last three weeks, I've rotated through two pairs of shorts, three shirts, three bikinis, one pair of long pants and a jacket. It's actually easier this way. You really need to think about what you take with you. My extras are a Walkman and four tapes, my journal and my navigation information. Other necessities are sunscreen, a hat, a knife, a flashlight, a mask, snorkel and fins, and for this trip, fly repellent.

Trying to live a simpler life opens your mind; for me, I can allow myself to enjoy the voyage and to discover my own strengths and weaknesses. I see how much clutter I live with at home, the clutter of material possessions and mental distractions. Voyaging on Hokule'a is a privilege, and I am honored to be here. The simplicity of living on the canoe is a luxury that is priceless.

August 17: I woke this morning to another beautiful day at sea, tow or no. [Hokule'a has been under tow by the escort vessel Kamahele the last four days as winds are light.3] In the hour before sunrise, I could see the shadow of the planet slowly erased by the approaching brilliance of the sun. For a brief instant, Hokule'a rode the line that divides night and day and then that line moved slowly away to the west, and we remained, bathed in golden light.

Today is our fourth day at sea and so far it's much like the previous three. We've been lucky to have sunny, mild weather and equally mild seas. Weather this good is a blessing; rough weather is physically and mentally demanding. In our present balmy weather condition, our crew motto has been "we have nothing but time." We have time to sing a song, even if we don't know all the words. Last night, Kaniela Akaka (a crew member from the Big Island) played his version of "Territorial Airwaves." The sweet sentimental melodies warmed our hearts with thoughts of home. We had time to have a birthday party for Chad (Baybayan, navigator, who turned 43) complete with Peach Marquesan (Bavarian) Cake. We have time to read books: "Moku Ula," "Mangareva," or a book about world weather systems. We have time to study navigation and to teach it to the rest of the crew. We had time for a laugh when Chad caught a malolo (flying fish) in his blanket; it was quickly sashimi'd and eaten. There is time to talk and laugh and to tell ghost stories under the stars. As an apprentice navigator, I have the time to listen to the swells and the wind and watch the stars turn through the night.

The most valuable use of the time we have out here is to think about and evaluate ourselves. I think about what I miss at home: poi, family and friends. The luxury of having this time lets me think about who I am both here and at home. Here, at sea, I am most directly confronted with myself. At times, that's scary. Sometimes I don't like what I see but I also see how I can change. Most of the time I see how far I've come in my life. Simplicity is the soul of voyaging and it strips each of us down to our true selves. Given the choice, despite heat, lack of sleep, the stomach flu, (it's going around) and an occasional bad joke, I have accepted the challenge to be me. That opportunity is a rare gift and, as such, there's no place in the world I'd rather be than right here, right now.

August 19: In the predawn light the swells around us look like a pod of whales rising and sinking beneath us and around us. The sea today, like yesterday, is calm enough to be a lake, so we're still being towed (by the escort vessel Kama Hele). This is the sixth day of our journey and according to our calculations it's nearly time to finish our (the apprentice navigators') segment of navigtion.

Of course, the plan has changed a few times since the trip started. Given the lack of wind in this area, in Hiva 'Oa we planned to tow 660 miles southeast in the direction of Noio Malanai (123 degrees, 45 minutes true.) We began on that course but estimated that we were drifting west. After three days or so we altered course to 'Aina Malanai (112 degrees, 30 minutes true.) We've decided to keep that course to gain easting-very important on this leg. For safety's sake easting takes us away from the danger of the Tuamotus (with many unexposed reefs and shoals). It also takes us to the longitude of our next stop, Pitcairn Island, at 130 degrees west.

When the apprentice navigators--myself, Moana Doi, and Aldon Kim (newly promoted from tool box man)--figure we've hit that longitude, we alert Chad Baybayan and our navigation experiment ends. From there, Chad takes over as navigator.

It's been quite a challenge. Because we've been lucky to have clear skies, the stars have been easy to read. We've been using all four of our navigation star lines through the night, but most significantly to us we've been able to steer with Hokule'a, the star, setting directly on our stern. Every night about 4 a.m. we try to get a latitude fix off of the star Schedir in Cassiopeia. It's hard at that hour despite the calm seas because darkness obscures the horizon. The canoe movement also makes accurate measurement difficult.

The biggest challenge has been to stay awake and alert. I manage about 6 hours sleep spread out in a 24-hour period. I'm extremely lucky in that respect to have others navigating with me. As a first-time navigator, I'm reconciled to the fact that we're being towed. We still control our course by directing the Kama Hele as to which direction to steer. Towing lets us get more sleep than if we were sailing. Although I'd rather be sailing, this is a good way to get broken in as a navigator.

"Where is that swell from?" "Where did that one go?" "Where is the moon setting tonight?" "How high was that star?" "How fast did we go today?" "How far did we travel overnight?" "Where are we?" "If we change course lines, what distance do we have left?" These are some of the questions we ask each other and try to answer every day.

Tomorrow, by 8 a.m., our part of the navigation will be over for a while. By a combination of star height measurements and dead reckoning, we estimate that we're nearly 130 degrees W. You at home know more accurately than we where we are. Regardless of whether the numbers match, the experiment has been a success for us because we've learned the process of navigation by experiencing it.

August 23: Two nights ago our tour of Lake Polynesia ended with our emergence from the back side of a squall line. [There has been little to no wind for much of the past couple of weeks, prompting the crew to dub the Pacific "Lake Polynesia."] We were met with a 6-to-8 foot white-fanged south swell that raged around and beneath us. The wind came in from the south, killing the afternoon's warmth and making night watch brutal. That night held the promise of squalls and heavy weather-adrenaline candy to the adventuresome among us. It had been far too easy so far, so the time had come for a real test.

Two days later, we're closer to Pitcairn (Island) but back in the lake. The swell remains with us, still at six feet. The continuous passage of low pressure systems south of us has produced a rainbow effect of swells. They curve around us from southwest, south and southeast in a barren blue landscape that rolls like the Waimea hills.

On days like those we've been having, it's the small things that keep us occupied on our canoe/island. One of the favorite pastimes is cracker bucket collection and decoration. One of the staples of the Hokule'a diet is Diamond Bakery royal cremes, soda crackers and saloon pilots. Crackers keep your stomach settled when you're seasick. They go with cocoa and peanut butter at night and are the perfect afternoon snack.

On a par with the crackers, however, are the white buckets they come in. They are a hot commodity among Hokule'a sailors because they're watertight, compact, and carry just enough stuff to last one night onshore. They also double as chairs, end tables, and step-stools. The pecking order for bucket ownership is always heavily debated until the captain steps in to restore order. In some instances, buckets are labeled with names prior to being emptied, a practice contrary to canoe protocol.

Once acquired, the bucket is decorated with the name and signature artwork of the owner. Sometimes this is a saying, a warning or a picture. Mine has a star compass and Manaiakalani (Maui's Fishhook, i.e., Scorpio). We each have at least one personal bucket and some have more. Onshore in Hiva 'Oa, the buckets became an identifying mark for the crew. We'd attempt to walk to various destinations but would always be able to catch a ride. People knew who we were because of the buckets we carried.

On board buckets are recycled in a variety of ways. We use buckets with the bottoms cut out in our new bathrooms. We use them to scoop ocean water for baths and washing. They carry tools or can be an extra bowl for mixing food. They stow our fishing gear and, with a perforated bottom, are used to drain wet line. We have "Malolo Express," which is a bucket on a long line which serves as a carrier of information and shared fish between the Hokule'a and (escort boat) Kama Hele crews.

So, to Diamond Bakery, thank you. Your crackers have soothed many an upset stomach and have made a cold night watch a little cheerier. Your buckets, however, keep our belongings dry and give us a sense of common identity.

August 26: Our first day after leaving Pitcairn (Island) is windy and chilly with swells rocking the canoe. We came to Pitcairn under much the same conditions-squally with a large swell that we'd climb up and speed down. It was 4:30 a.m. on the 24th: a gray dawn, and the shape of a small gray island emerged out of the rain like a dream. Gary Yuen, from Honolulu, was the first to actually see it, winning the "dollar-dollar" bet that he made the night before, as to who would have the first sight of land. It was a rough six hours from that point through squalls and swells, but at last the sky opened to let the sun shine down on a tiny, green gem in a calm, blue sea.3

We spent 36 hours at Pitcairn visiting the 42 people of 14 families that live there. We saw most of the island-1 mile by 1 and a half miles. We were fed and offered hot showers, a welcome treat after 11 days at sea. We visited the school where the 10 school children, aged 8-15, serenaded us and asked us normal school-kid questions about our journey. We also hosted the residents to a dinner. It was a potluck, although we told them we'd provide everything. Just as at home, Pitcairners don't go to a party without bringing something. We also gave each family a package of food from our stores.

Isolation has its price. The islanders grow a great deal of produce there, but they can't cover every need on their own. Pitcairn depends on a freighter twice yearly to bring in supplies. Of course, it's never reliable and is expected to be four months late this year. The Pitcairn store's stock is rapidly depleting, sugar especially. The problems of living on a small island became readily apparent. There's the drain of the youthful population to New Zealand, Australia and England. Currently, there are no residents in their 20s, and only a couple in their 30s. The way of life on the island no longer appeals to the young. They have the world to explore.

The tourism engine is beginning to drive Pitcairn. Each family produces their own T-shirts, maps and patches, as well as selling books about the "Mutiny on the Bounty" and the history of the island. "Yachties" are fairly regular visitors, as are French navy vessels and a few cruise ships (with 600 passengers). The latest debate is over whether or not they should build a small airstrip, therefore bringing in commercialism to a degree that makes the open-hearted islanders cringe.

Another issue that will soon affect the lives of island residents is over land tenure. A proposal is in the works to allow foreigners to buy land in Pitcairn, to be forfeited if they leave. The catch is that the same regulation would apply to residents. If they should leave, their land also would revert to the government.

Pitcairn is on the verge of big changes from a community holding onto the simple ways of the past, to a more financially secure, but commercial lifestyle. What is the true value of Pitcairn, and which lifestyle brings greater rewards? It would be interesting to go back in five, ten or fifteen years to see what choices were made. And to look back at our own island history and see how our own choices, when in that same position, have changed Hawai'i.

August 30: Our second day on Mangareva is a day of work. We arrived yesterday to the full round of ceremonies, protocol and food. We actually saw Mangareva completely for the first time after catching a glimpse at 3 o'clock Saturday afternoon. We saw Temoe, the intervening atoll at 1:30 p.m., a gray fringe on the surface of the sea that darkened and thickened into small coral islands. It took teamwork to find it. Tim Gilliom of Maui saw the change in the swell. I had calculated the time we'd see it, by keeping track of speed and distance. Aldon Kim's "X-ray" vision first spotted it.

A little over an hour after that jubilant sighting, we saw Mangareva's two peaks, like the horns of a manta ray, faint and far in the distance. Later in the evening, we hooked up a line to our escort boat, the Kama Hele, and towed through the night to be in positon to make landfall in the morning. Through the night, the shadows of islands grew slowly more distinct, and as the sun rose, we saw the Gambiers clearly. It was an emotional 24 hours for all of us.

My watch, nicknamed "the Zoo" for all the animals within-Tava Teikihe'epo Taupu, the puaka; Kealoha Hoe, the koloa (duck); Mona Shintani, the tika (tiger); Kaniela Akaka, the liona; and myself, the popoki (cat)-had our ceremonial last five minutes on watch together. We all put our hands on the steering sweep and steered together, singing one last song, and making our respective animal noises.

As we were about to enter the reef of the Gambiers, we said a crew pule (prayer) to give thanks for a safe trip, and for all the sights, sounds, laughter and amazement we had shared in the last three weeks at sea. Our crew counted ourselves extremely lucky to have seen eight islands during our leg. Eight landfalls, eight new worlds to experience, and eight new sets of friends.

That's a Hokule'a record.

It was also a sad moment for all of us, the end of our canoe time and almost the end of our common journey. For myself, it was a time to thank the people I had sailed with for three weeks. Along the way, we discovered in each other familial relationships, a love of Santana at sunrise, a shared repetoire of Hawaiian songs, and most importantly, trust and respect.

We are already making plans to see each other when we get back and to have reunions later when the voyage is over. Whether or not these plans pan out, we know that we share a bond that only Hokule'a can create among people: of being, for a short span of time, the resident of a canoe/island community, wholly dependent on each other to survive passage over the vast ocean.