Mapping the World Wide Voyage

The PVS navigation team is currently planning the World Wide Voyage (WWV). The mission of the voyage is to mālama, to take care of, our homes – our canoes, islands and honua (world) and to navigate toward a healthy and sustainable future.

During the four-year long Worldwide Voyage, Hōkūle‘a's crews will have numerous opportunities to stop, visit, and explore. The stops will be selected based on safety criteria as well as decisions about where Hawaiian values and practices, such as mālama, can best be shared with others and where we can best learn from others about what they are doing for the health and safety of future generations.

During the voyage, crew members will report on discoveries and engage teachers and students, via the Worldwide Voyage weblog, on such topics as societies and cultures, the natural environment and sustainable practices and initiatives, and food and health issues.

Following the Wind and Warm Weather: Sailing in the Tropics

As much as possible, in her journey around the world, Hōkūle‘a will use non-carbon-based renewable energy, like wind and sunlight.

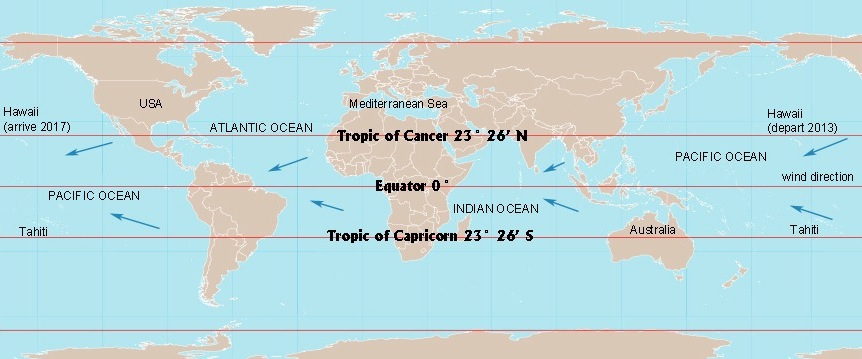

To take advantage of prevailing gentle-to-moderate easterly trade winds and warm temperatures, Hōkūle‘a will generally sail north-south and westward within the tropics. (The tropics are the area of the globe between the Tropic of Cancer at 23˚ 26′ N and the Tropic of Capricorn at 23˚ 26′ S.)

Mapping the WWV. For a larger image, click on map below and zoom in.

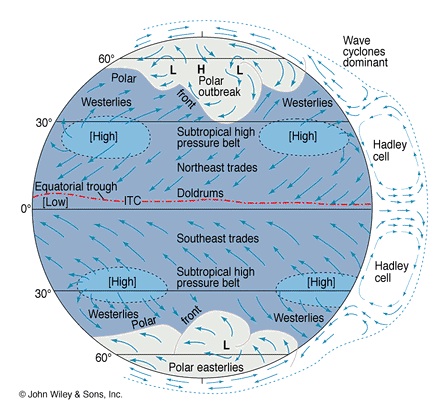

The Trade Winds

In the northern hemisphere tropics, the trade winds blow predominantly from the northeast; and in the southern hemisphere tropics, from the southeast. The winds are generated by two belts of high atmospheric pressure, one around 25°-30° N and the other around 25°-30° S.

For explanations of how wind is generated, see "Global Scale Circulation" in The Physical Envrionment and "Origin of Wind" in JetStream.

Crossing the Equator

Hōkūle‘a will likely cross the equator four times during the voyage:

- From Hawai’i to Tahiti, at the start.

- From Australia to the Maldives and the Red Sea, in the Indian Ocean, on the way to the Mediterranean Sea. (Alternative Route: South around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope.)

- From the Panama Canal to Rapanui in the Pacific, with a stop in the Galapagos Islands, and later westward to Aotearoa.

- From Aotearoa back to Hawai’i via Rarotonga, Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands.

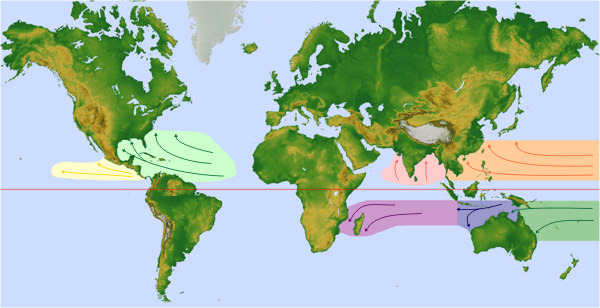

Avoiding Tropical Cyclones

Tropical cyclones are the most serious weather risk to vessels sailing in the tropics. (See "View Lesson 14 - Hurricanes" for a NOAA video on tropical cylcones; see also "Tropical Cyclone Introduction." Tropical cyclones are also called hurricanes and typhoons.)

There are seven areas in the tropics where tropical cyclones form, four in the northern hemisphere and three in the southern.

Map from NOAA’s "Tropical Cyclone Formation Regions."

These powerful storms, with winds over 74 mph (64 knots), form during periods of hot weather, generally in summer and fall.

To avoid tropical cyclones, Hōkūle‘a will sail in the tropics in the winter and spring:

- Northern hemisphere winter-spring: December to May

- Southern hemisphere winter-spring: June to November

(For an explanation of why the seasons in the northern and southern hemispheres are opposite of each other, see "Seasons" in The Physical Envrionment.)

In the northern hemisphere Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the tropical cyclone season begins in May-June and extends to October-November. In the Indian Ocean, the season is longer, beginning in April and extending to December. In the Northwestern Pacific there is no official season as tropical cyclones form throughout the year, but the main season is from July to November, with a peak in late August/early September.

In the southern hemisphere, the tropical cyclones form from November-December to April-May.

Safe Havens around the Equator

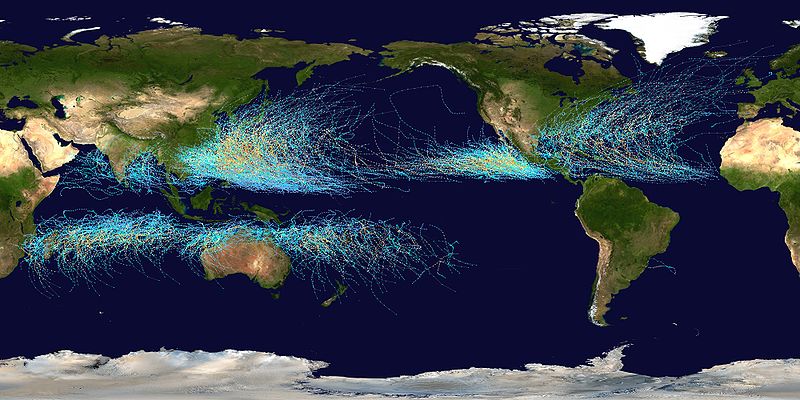

Contrary to what one might expect based on high equatorial temperatures, the area within 5° of latitude north and south of the equator is, with rare exceptions, free of cyclones.

In the chart below, the light colored tracks represent tracks of tropical cyclones. The dark blue band extending horizontally through the center of the map represents the equatorial belt (10˚ wide) where tropical cyclones generally do not form. (For a larger image, click on map below and zoom in.)

Worldwide Tropical Cyclones from 1985 to 2005. Wikimedia Commons.

Around the equator, Coriolis Force is insufficient to circulate warm rising air masses into cyclones. (See Coriolis Force in The Physical Envrionment; also “Meteorology” under "Coriolis effect" in Wikipedia.)

The Maldives, in the Indian Ocean, an archipelago of atolls extending from 0° 40' S to 7˚N southwest of India and Sri Lanka, could provide a safe haven as Hōkūle‘a waits for the northern summer-fall hurricane season to end before sailing north to and through the Red Sea in winter and spring.

Maldives Map from World Atlas (English). Holt Rinehart Winston. 2006 © Mapquest.

Excursions Outside of the Tropics

Hōkūle‘a will travel to the subtropics (i.e., outside the tropics, north of the Tropic of Cancer or south of the Tropic of Capricorn) to get around the continent of Africa and to sail to Aotearoa. These subtropical excursions will take place in the spring, after subtropical winter storms subside.

Hōkūle‘a will remain in the cooler, safer subtropics during the summer-fall hurricane season before returning to the tropics in the following winter-spring.

Possible Subtropical Excursions

- North of the Tropic of Cancer: from the Indian Ocean via the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.

- South of the Tropic of Capricorn: an alternate route from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic: around Africa's Cape of Good Hope.

- North of the Tropic of Cancer: from the Caribbean to the East Coast of the United States.

- South of the Tropic of Capricorn: Aotearoa, with a sail around North Island.

Hōkūle‘a has voyaged in the subtropics three times before:

- In November-December, 1985, Hōkūle‘a sailed from Rarotonga (21° 30' S) to Aotearoa (35° 12' 0 S); and back to Rarotonga in May 1986.

- In May 1995, Hōkūle‘a and Hawai’iloa were shipped to Seattle, Washington (47° 36' N), from where Hōkūle‘a sailed south to San Diego, California (32° 44' N), and Hawai’iloa went north to Juneau, Alaska (58° 18' N).

- In May-June 2007, Hōkūle‘a sailed from Yap Island to Tokyo, Japan (35.40 N).

International Maritime Piracy and Travel Warnings

Hōkūle‘a will avoid or take special preautions in areas known for maritime piracy, like the waters around Indonesia, particularly the Malacca Straits, and the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa.

The U.S. State Department issues Travel Warnings, "when long-term, protracted conditions ... make a country dangerous or unstable." These warnings will be considered as PVS plans for the places Hōkūle‘a will visit.

Selecting the Best Sailing Routes

The Worldwide Voyage will be segmented into sailing routes (legs) that will be designed to require not more than a month at sea. Crews will be selected to complete each leg of the voyage.

For each leg, the PVS navigation team will develop a course strategy and a sail plan, based on the sailing capabilities of Hōkūle‘a and the likely winds and weather conditions between the departure point and destination during the month that the route will be sailed. For best conditions for a successful sail within the time frames for each leg, routes should have at least a 75% average of favorable winds (winds from the beam or back of the canoe).

Basic data on winds are published in the Atlas of Pilot Charts:

Pilot Charts depict averages in prevailing winds and currents, air and sea temperatures, wave heights, ice limits, visibility, barometric pressure, and weather conditions at different times of the year. The information used to compile these averages was obtained from oceanographic and meteorologic observations over many decades during the late 18th and 19th centuries.

The charts are intended to aid the navigator in selecting the fastest and safest routes with regards to the expected weather and ocean conditions.

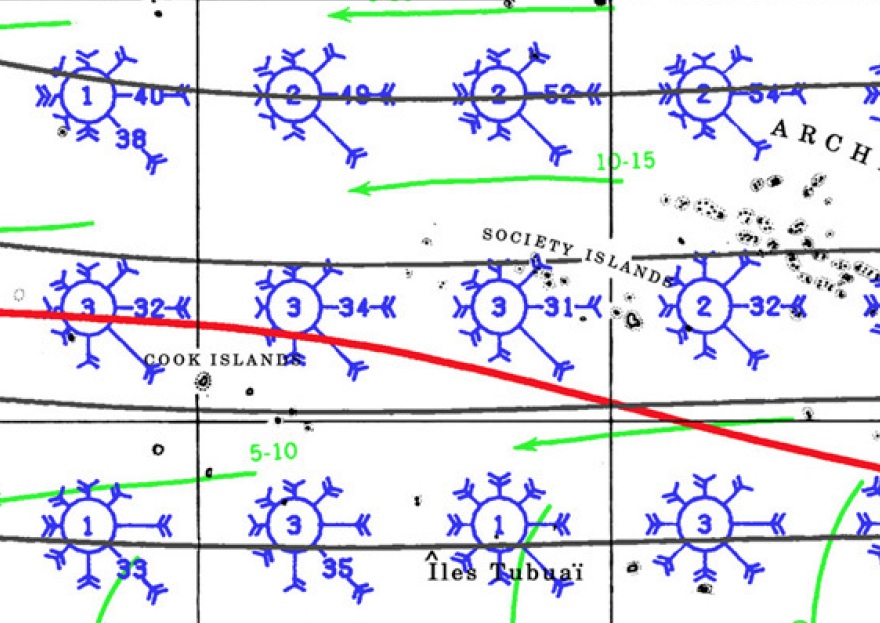

Links to digital versions of many of the charts are available online at website like sailnet.com. The following image is a section of the chart for the South Pacific in May, depicting average winds between Tahiti and the Cook Islands, using "wind roses" to present the data:

Winds between Tahiti and Rarotonga in May. Atlas of Pilot Charts South Pacific Ocean, 1998

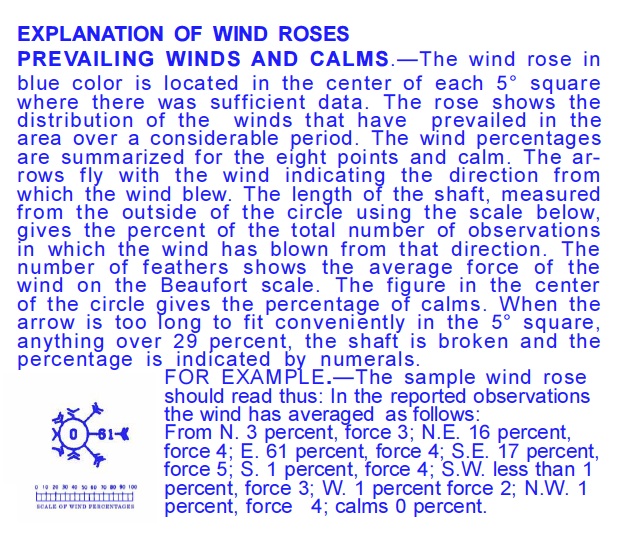

How to read a wind rose (the blue circles in the illustration above):

Also useful in sail planning is the 42-volume Sailing Directions (published by NGA), which describes features of coastlines, ports and harbors, and local winds, weather, currents, and tides (in 37 Enroute volumes); as well as "country-specific information such as firing areas, pilotage requirements, regulations, search and rescue information, ship reporting systems, and time zones" (in four Planning Guide volumes).

Navigation

The open-ocean legs will be navigated without instruments.

Continuous Orientation

The Worldwide Voyage is a real-world cultural and education project. PVS will continuously monitor data on global conditions that may pose a danger to the canoe and crew; plans will be made and modified, as needed, to reduce the risk of harm. Variations in global weather and other factors may necessitate changes in the sail plan during the four years of the Worldwide Voyage.

Resources

Google Map with distance and bearings tools: www.acscdg.com

Google Map with annual incidents of international maritime piracy: International Chamber of Commerce / Maritime Bureau website.

National Ocean and Atmospheric Adminsitration (NOAA). JetStream, the National Weather Service Online Weather School.

Monterrey Insitute for Technology and Education. NOAA Video Lessons (1-15).

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Atlas of Pilot Charts. (Links to digital pdf-versions of many of the charts are available online at website like sailnet.com.).

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Sailing Directions (Planning Guide and Enroute). (Zip files, Windows-only executable, of Sailing Directions are available at Adrift at Sea--Dan's Blog, along with links to the digital pdf-versions of the Pilot Charts.)

Polynesian Voyaging Society. Designing a Course Strategy.

Polynesian Voyaging Society. Wayfinding (Non-instrument Navigation).

Ritter, Michael E. The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography. 2006. (Online textbook, in development.)

US State Department: Travel Warnings.

World Atlas (English). Holt Rinehart Winston. 2006 © Mapquest.