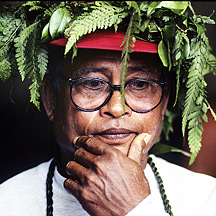

Pius “Mau” Piailug (1932-2010)

Pius Mau Piailug, master navigator from Satawal, Yap State, Micronesia navigated Hōkūle‘a on her first voyage to Tahiti in 1976; subsequently, he taught Hawaiians and other Polynesians to the arts of navigating without instruments.He passed away on Satawal on July 12, 2010. For a detailed biography, see Mau Piailug, at Wikipedia.Mau teaching navigation to his nephew on Satawal. From "The Navigators: Pathfinders of the Pacific," posted on YouTube by Documentary Educational Resources.

Mau, on the Origin of his Navigation, on Pulap, posted on YouTube by Indigenous Knowledge.

Piailug's greatest lesson is that we are a single people

Posted: July 29, 2010 in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser

Pius “Mau” Piailug of Micronesia reconnected native Hawaiians with their maritime past and counseled the younger generation to build upon that knowledge.

Mau. Photo by Monte Costa

The effort to recognize the immense contribution of the late master navigator and mariner, Pius "Mau" Piailug, to the re-emergence of oceanic wayfinding through non-instrument navigation, although well-intentioned, misses the mark ("Piailug was giant in voyaging rebirth," Off The News, July 14).

For anyone who had the privilege to know Mau, and for the fortunate few who had the opportunity to study under him, it is clear why your commentary is off-base: "What's so ironic is that Hawaii could have lost the connection to its indigenous maritime past without the gift of a master navigator who was not even native Hawaiian."

Mau Piailug, in his teaching opportunities among the many voyaging organizations here and throughout the Pacific, never identified himself or his students as being different or belonging to the labels that are imposed by the many experts who feel the need to define people by geographical boundaries.

For the pupils he generously shared his time with, Mau viewed and treated us as an oceanic ohana, defined not by an ocean that separated us, but rather an ocean that joined us around common traditions and a passion for an island lifestyle.

While best known for his navigational ability to wayfind, and an even greater skill as the consummate mariner, Mau was also a teacher dedicated to sharing unselfishly.

His lessons revolved around the central social theme that knowledge had no value unless you pass it on, and that navigation/ wayfinding gained its value not simply from one's abilities as a master seafarer, but in the ability of the practitioner to transfer that skill into becoming a leader and steward within his or her community.

I paraphrase some thoughts shared with the voyaging community from Mau's nephew, Thomas Raffipiy, when he last visited with Mau:

"On a cool summer evening in 2005 on Satawal, as Mau and I visited on the beach of Nemaenong (one of our family villages), watching the sun set in the west, Uncle Mau shared this charge with me:

'I have laid the stick that connects people together. Now it is up to you, your generation and the generations to come, to build upon that stick a bridge that will ensure the free sharing of information and teaching between the two peoples until the day we become united again as a single people, as we were once before; before men separated us with their imaginary political boundaries of today's Polynesia and Micronesia.'"

Addressing the many men and women who have directly benefited from Mau Piailug's unselfish sharing, generous spirit and eloquent and thought-provoking counsel, I ask that they keep his memory alive as an example of the difference that one incredible individual can make to the betterment of society and communities that value a life of friendship.

Honor him by recognizing the common human kinship that makes us all a global ohana, a standard that Mau strived to live his life by. [end of Honolulu Star-Advertiser article by Kalepa.]

More about Mau, from his nephew, Tom Raffipiy (quoted in "Legendary Master Navigator Pius “Mau” Piailug sails on" by Bill Jaynes and Tom Raffipiy in Kaselehlie Press, Kolonia, Pohnpei, July 26, 2010):

“In his native Satawalese vernacular “mau” means strong, strength, hard, hardened, and mature, among other definitions. Truly, Pius “Mau” Piailug lived up to the nickname given to him in his early adulthood. The name was supposedly given to him to describe his uncanny physique which was then thought of as a physical defect. The ripples of muscles on his back were likened to the rough shells of hawksbill turtles. However he got the nickname “Mau” one can be certain that it was given out of love and affection as was the normal practice. Probably no one realized how the name would shape the character of the man who defied cultural belief to safeguard a dying art of Oceania – non-instrumental navigation.

“Mau was naturally strong and courageous. Mau would have beem the first to admit that he might have not known as much “talk of the sea” as most navigators of his time did, but I knew him to have more courage and to be more fearless than any of them. Mau would never allow himself to doubt his decisions and navigational tactics and that served him well throughout his life. He thrived on challenges and rarely stayed on the land. He dedicated his whole life to voyaging and to teaching. That was his passion.

“Mau’s points of view frequently sparked controversies as he would always speak his mind and often challenged other people’s points of views that he believed were not in line with cultural practices and beliefs. He was a man of few words but if presented with the opportunity, he would speak in burst of words in rapid fire fashion that could be intimidating to those who didn’t know him.

“Among his major pet peeves was the introduction of Christianity and western education in the islands. Like many island elders, he believed western religious practices and schools contributed to the rapid erosion of cultural arts and sciences that have kept the Pacific Island cultures alive for generations.

“Like men of his age and those before him, Mau believed that real men drink alcoholic beverages. Mau drank most of his life and that probably contributed to the downward spiral failure of his health.

“Mau fulfilled the callings of the traditional navigators and much more. He did his part in feeding the islands and upholding the honorable legacy of “pwo navigators.” Unlike many navigators, Mau was so giving of his knowledge and willing to teach whoever was willing to learn. Every moment was a teaching moment to Mau. He loved the dedication of the Polynesian people to learning traditional navigation, and it’s for that reason that he dedicated half of his life to teaching traditional navigation to the Polynesian people especially the Hawaiians. The Hawaiian people were very special to Mau.

“Mau left behind a legacy that is unparalleled and unmatched. Mau will be remembered by his generous gift of pride and self-identity to the people of the Pacific. His will be a legacy of teaching islands rather than individuals. Mau was a visionary man with great conviction in his knowledge, tremendous physical and mental strength, and unwavering courage to break the taboos of the teaching of navigation in order to preserve the precious “talk of the sea.”

Reflections on Mau

Background on Mau (Polynesian Union speech, 1997)

Mau’s island, Satawal, is a mile and a half long and a mile wide. Population 600. Navigation's not about cultural revival, it's about survival. Not enough food can be produced on a small island like that. Their navigators have to go out to sea to catch fish so they can eat. Mau was not like me, who learned by using both science and tradition. I started at an old age, at about 21. He started at one. He was picked by his grandfather, the master navigator for his people, taken to the tide pools at different parts of the island to sit in the water and sense the subtle changes in the water's movements. To feel the wind. To connect himself to that ocean world at a young age. His grandfather took him out to sail with him at age four. Mau told me that he would get seasick and when he was seven years old, his grandfather would tie his hands and drag him behind the canoe to get rid of that. This was not abuse. This was to get him ready for the task of serving his community as a navigator.

Learning Navigation from Mau, after Hōkūle‘a capsized on its way to Tahiti in 1978-1980

Most of all, we realized we did not know enough. We needed a teacher. Mau became essential. Mau is one of the few traditional master navigators of the Pacific left. And Mau was the only one who was willing and able to reach beyond his culture to ours.

I searched for Mau Piailug. Finally, I found him and flew to meet him. Mau is a man of few words, and all he said in answer to my plea for help was, "We will see. I will let you know." For several months I heard nothing. Then one day I got a phone call; Mau was going to be in Honolulu with his son the next day. When Mau arrived here back in 1979, he said, "I will train you to find Tahiti because I don't want you to die." He had heard somehow that Eddie had been lost at sea.

I asked him to teach me in the traditional ways. But Mau knew better. He said, "You take paper and pencil! You write down! I teach you little bit at a time. I tell you once, and you don't forget." He recognized that I could not learn the way he had learned.

Mau learned to turn the clues from the heavens and the ocean into knowledge by growing up at the side of his grandfather – he had been an apprentice in the traditional way. He had learned to remember many things through chants and would still chant to himself to "revisit information."

Mau's greatness as a teacher was to recognize that I had to learn differently. I was an adult; I needed to experiment, and Mau let me. He never impeded my experimenting and sometimes even joined in.

I never knew when a lesson started. Mau would suddenly sit down on the ground and teach me something about the stars. He'd draw a circle in the sand for the heavens; stones or shells would be the stars; coconut fronds were shaped into the form of a canoe; and single fronds represented the swells. He used string to trace the paths of the stars across the heaven or to connect important points.

The best was going out on my fishing boat with Mau ... every day! I watched what he watched, listened to what he listened to, felt what he felt. The hardest for me was to learn to read the ocean swells the way he can. Mau is able to tell so much from the swells-the direction we are traveling, the approach of an island. But this knowledge is hard to transmit. We don't sense things in exactly the same way as the next person does. To help me become sensitive to the movements of the ocean, Mau would steer different courses into the waves, and I would try to get the feel and remember the feel.

Mau can unlock the signs of the ocean world and can feel his way through the ocean. Mau is so powerful. The first time Mau was in Hawai'i, I was in awe of him-I would just watch him and didn't dare to ask him questions. One night, when we were in Snug Harbor, someone asked him where the Southern Cross was. Mau, without turning around or moving his head, pointed in the direction of a brightly lit street lamp. I was curious and checked it. I ran around the street light and there, just where Mau had pointed, was the Southern Cross. It's like magic; Mau knows where something is without seeing it.

I spent two Hawaiian winters with Mau. In the summer, ninety-five percent of the wind is trades, so it's easy to predict the weather. Tomorrow is going to be like today. But in wintertime you have many wind shifts. When I had spent enough time with him, I realized that he was not looking at a still picture of the sky. If you took a snapshot of the clouds and asked him, "Mau, tell me what the weather is going to be," he could not give you an answer. But if you gave him a sequence of pictures on different days, he would tell you.

He said, "If you want to find the first sign of a weather change, look high." He pointed to the high-level cirrus clouds. "If you see the clouds moving in the same direction as the surface winds, then nothing will change. But if you see the clouds moving in a different direction, then the surface winds might change to the direction the clouds are moving. That's only the first indication, but you don't really know yet. If clouds form lower down and are going in the same direction as the clouds up high, there is more of a chance that the winds will change in that direction. When the clouds get even lower then you know the wind direction will change."

Satellite technology was in its infancy then, and many times Mau's predictions would be right and the National Weather Service would be wrong.

He used the same clouds that we use to predict the weather--mare's tails, mackerel clouds. But in his world, he practices a kind of science that is a blend of observation and instinct. Mau observes the natural world all day. That's how he relates to nature. There are no distractions, so his instincts are strong.

In November of 1979, Mau and I went to observe the sky at Lana'i Lookout. We would leave for Tahiti soon. I was concerned-more like a little bit afraid. It was an awesome challenge.

Then he asked, "Can you point to the direction of Tahiti?" I pointed. Then he asked, "Can you see the island?"

I was puzzled by the question. Of course I could not actually see the island; it was over 2,200 miles away. But the question was a serious one. I had to consider it carefully. Finally, I said, "I cannot see the island but I can see an image of the island in my mind."

Mau said, "Good. Don't ever lose that image or you will be lost." Then he turned to me and said, "Let's get in the car, let's go home."

That was the last lesson. Mau was telling me that I had to trust myself and that if I had a vision of where I wanted to go and held onto it, I would get there.

Year after year he came and took us by the hand. He cares about people, about tradition; he has a vision. His impact will be carried beyond himself. His teaching becomes his legacy, and he will not soon be forgotten.

On Mau's Legacy (Polynesian Union speech)

When I did my first voyage and came home in 1980, Mau said everything you needed to know about navigation is in the ocean, and it is all there for you to learn. But because of your age, you'll never see it all. He said if you want Hawai'i to have a navigator that knows it all and sees it all, send your children.

Mau is the last. He's 64 years old now. And he is the last to be initiated in the ceremony called pwo, which is a graduation of deep sea navigators. Not mastery. And let's keep in mind, I'll make it real clear right now. I'm not a master navigator, by a long shot. I'm just a student. Mau graduated because he could sail long. But mastery is only something that is bestowed upon a deep sea navigator upon the death of his teacher. Mau became a master navigator when his grandfather died. Mastery is not accomplishment, it's responsibility. He had the responsibility to carry on the survival of his people. Unbroken tradition, 3,000 years old.

Mau has a dilemma. He is one of five master navigators left in Micronesia. He's 64 years old, and he's the youngest. Great influences are changing the way the young people look at life. Very confusing, turmoiled time. Young people are not learning. One of the things that he told me years ago is that a master navigator's life is not fulfilled until his death, when someone is there to take on his legacy.

That's Mau's dilemma. Every year Mau would come, we'd ask him to help us -- teach us about the old ways. He would come. Unselfishly. This act of great caring and giving. And every time he'd come, we'd sit down and talk about that dilemma. 1994, when he came back he simply told me it's too late. I am too old, our children have too much to learn, it's too late. Something I never wanted to hear. But he said, it's okay. All navigators find a way out. When they put me in the ground, meaning when he's buried, it's all right because I already planted the seed in Hawai'i. He said a very interesting thing. He said, when my people want to learn, they can come to Hawai'i and learn about me. Mau does not separate navigation as cultural revival. It's about a way of life. The issue is his people will never recover this tradition until they want to do it.

Remembering Papa Mau Piailug - Life In A Day Version

Lāna‘i Lookout, O‘ahu, July 24, 2010. Posted on YouTube by makahastudios.