The World Remembers Mau ...

- Kaselehlie Press (Pohnpei), July 26: Legendary Master Navigator Pius “Mau” Piailug sails on

- News Release, Government of the Federated States of Micronesia, July 23: Master Navigator "Mau" Piailug Dies on July 12, 2010

- The Economist, July 22: Pius Mau Piailug, master navigator, died on July 12th, aged 78

- Washington Post, July 21: Micronesian who sailed by navigating sun and stars

- Saipan Tribune, July 19: Sons of Mau Piailug talk about the master navigator

- The New York Times, July 17: Star Man

- The Wall Street Journal, July 15: Pacific navigator kept sailing techniques afloat

- Tahiti Presse, July 15: Hōkūle‘a navigator Mau Piailug

- The Star Advertiser, July 13: Voyager guided rebirth of culture

Honolulu Star Advertiser. July 13, 2010.

Voyager guided rebirth of cultures

By Gary T. Kubota. Star Advertiser Photo.

The way-finding navigator from an island of less than a square mile who ushered in a renaissance in open-ocean traditional native sailing across the Pacific has died.

Mau Piailug, 78, died Sunday night and was buried yesterday (Hawaii time) on his home island of Satawal in the western Pacific, said Kathy Muneno, a spokeswoman for the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Piailug was the navigator who reintroduced Hawaiians to traditional Pacific navigational methods using the stars, moon, wind, currents and birds to find distant lands.

In 1976 he was the navigator sailing aboard the double-hulled sailing canoe Hokule'a on its historic voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti.

The Hokule'a voyage supported the assertion that Polynesians were capable of long-distance voyages centuries before European explorers.

Piailug had suffered from diabetes for many years.

Polynesian Voyage Society President Nainoa Thompson said Piailug's contribution to restoring the cultures of Pacific islanders was immense.

"Thousands of people are sharing in the sadness," Thompson said. "His contribution to Hawaii and humankind is immeasurable."

In the mid-1970s, Piailug chose to share his knowledge of Pacific way-finding with native Hawaiians when the island cultures here and in Micronesia were experiencing rapid westernization.

Piailug hoped that by sharing his knowledge, the information would be stored elsewhere and would be shared with his people in the future.

The historic Hawaiian voyage to Tahiti in 1976 helped to restore pride in Pacific island cultures and built bridges among various Pacific island cultures through double-hulled canoe voyaging.

Besides Hawaii, other island cultures have formed voyaging societies to promote native voyaging, including in Taiwan, New Zealand, Samoa, Fiji, Guam, Saipan, Palau, Chuuk, Pohnpe, the Marshall Islands and Tahiti.

Satawal island resident Thomas Raffipiy recalled as a youth the night when Piailug consulted with his family and made the decision to help the Hawaiians.

Traditionally, the knowledge was passed down through the family and did not cross cultures.

"It was a decision that he didn't take lightly," said Raffipiy, Piailug's nephew. "He was among the youngest of the surviving navigators and hoped the knowledge stored somewhere with someone would come back. ... Everything he said has come to pass."

Ben Finney, a founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, said Piailug was driven to help by his vision of what needed to be done to revive native cultures through sailing, including Satawal islanders.

"He said, 'That's exactly what we need,'" recalled Finney, a former professor at the University of Hawaii.

Finney said Piailug became well known among Polynesians from New Zealand to Hawaii for the generous way in which he shared his knowledge of way-finding navigation.

"He was really an aid giver of ancient knowledge," Finney said.

Piailug's work came full circle during the 2007 voyage to his home island of Satawal, when Hawaii crews delivered the double-hulled canoe Alingano Maisu as a gift to Piailug.

That year, for the first time in a half-century, Piailug held a "Po" ceremony to induct master navigators into the Weriyeng school of navigation. The group included five Hawaiians and about 10 Micronesians, including his son, Sesario Sewralur.

Sewralur, the captain and navigator of the Alingano Maisu, teaches native navigation at a community college on Palau.

Thompson said to honor Piailug, the Hokule'a plans to sail around the Hawaiian Islands in the near future with crews of young people.

"It's a very important time to focus on all our teachers, honor them and celebrate them," Thompson said. "We know how much he loved Hawaii, and we know how much he loved the people."

Piailug is survived by more than a dozen children and numerous grandchildren.

Tahiti Presse. Thursday, July 15, 2010

Former Hokule'a navigator Mau Piailug dies at 78

The way-finding navigator Mau Piailug, 78, died Sunday night and was buried on his home island of Satawal in the western Pacific, a spokeswoman for the Polynesian Voyaging Society announced.

In 1976, Piailug was the navigator sailing aboard the double-hulled sailing canoe Hokule'a on its historic voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser reports on its website.

The Hokule'a voyage supported the assertion that Polynesians were capable of long-distance voyages centuries before European explorers.

Piailug had suffered from diabetes for many years, according to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Polynesian Voyage Society President Nainoa Thompson said Piailug's contribution to restoring the cultures of Pacific islanders was immense.

The historic Hawaiian voyage to Tahiti in 1976 helped to restore pride in Pacific island cultures and built bridges among various Pacific island cultures through double-hulled canoe voyaging.

Besides Hawaii, other island cultures have formed voyaging societies to promote native voyaging, including in Taiwan, New Zealand, Samoa, Fiji, Guam, Saipan, Palau, Chuuk, Pohnpe, the Marshall Islands and Tahiti.

Another former Hokule'a crewman, Clifford K. Ah Mow, also died a few weeks ago. Ah Mow died in April, at the age of 67, after a bout with cancer.

Wall Street Journal. July 15, 2010

Pacific Navigator Kept Sailing Techniques Afloat

BY STEPHEN MILLER

Mau Piailug sailed among the islands of the Pacific, using the stars and waves for guides, and showed how the islands may have become populated.

Mr. Piailug, who died Sunday at age 78 on his home island of Satawal in the Western Pacific, taught traditional navigating techniques to Hawaiians seeking to recapture the ways of their ancestors.

In 1976, Mr. Piailug was at the tiller during an epic trip of 3,000 miles to Tahiti from Maui in a 60-foot double-hulled sailing canoe, accomplished without navigational equipment.

The voyage, which was hailed for its audacity and featured in a National Geographic ... (must be a subscriber to the WSJ to read the complete article).

EDITORIAL New York Times. July 17, 2010

Star Man

By LAWRENCE DOWNES

Mau Piailug will never be as famous as Capt. James Cook, a master of the classic European feat of discovering places with people already in them. But Piailug, who died last week at the age of 78, could have matched Cook’s voyaging island for island across the vast immensity of the Pacific, and without charts, compass or sextant. He was a palu, a master navigator, one of the last experts in the ancient art of Pacific Ocean wayfaring.

Crossing an open ocean without instruments in knife-edged canoes, as the Polynesians did a thousand years before Cook, is one of the great achievements in human exploration. To those of us who are blind to the night sky, and deaf to the language of clouds, currents and ocean swells, it seems like a mystical or superhuman act. It is not — the palu’s skill is an achievement of reason, memory and calculation, though a staggering one.

Mr. Piailug (pronounced pee-EYE-loog), a native of the Caroline Islands, began his training as boy, studying chunks of coral on a woven mat. Over decades, he learned an age-old map of his Micronesian universe. On it were etched hundreds of star names, the habits of fish and birds, landmarks and routes through reefs and shoals. He earned wide renown in 1976, when he led a daring 6,000 mile voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti and back in a doubled-hulled canoe, the Hokule‘a.

The Hokule‘a did not resolve the question of whether the first prehistoric voyages to Hawaii had been accidental or intentional, but it did show that long-distance navigation was still possible.

The voyage was a watershed moment for Hawaii, whose people have been slowly pulling their trampled folkways back into existence, the way fishermen in Pacific mythology were thought to have pulled whole islands from the depths. In Hawaii, until Mau Piailug shared his knowledge, the palu’s art had been lost for a millennium. His Hawaiian student Nainoa Thompson became a navigator in his own right, and many voyages have followed, thanks to an extraordinary act of cross-cultural generosity.

Saipan Tribune. Monday, July 19, 2010

Sons of Mau Piailug talk about the master navigator

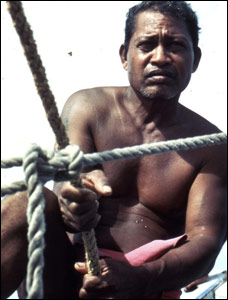

By Clarissa David. Photo: Sam Low.

Antonio Piailug's fond memories of his father, legendary Micronesian navigator Mau Piailug, were about the countless voyages they made together.

Antonio Piailug's fond memories of his father, legendary Micronesian navigator Mau Piailug, were about the countless voyages they made together.

“I used to sail with my father in Yap and Chuuk since I was 6 years old,” the younger Piailug told Saipan Tribune in a telephone interview.

With unsurpassed skills in journeying across the Pacific without the use of any navigational instruments, Mau Piailug was considered a palu, a master navigator that only uses of ancient methods of wayfaring.

On July 12, Mau Piailug, the last of the traditional master navigators, passed away on his home island of Satawal, state of Yap, in the Federated States of Micronesia. He was 78.

Mau Piailug was well-known for having navigated the Hokule'a, a Polynesia double-hulled voyaging canoe, in the 2,500-mile journey from Hawaii to Tahiti on its maiden voyage in 1976.

According to his son Henry Yarofalpiy, they found out about his father's death through a call from their relatives back in Satawal.

Mau Piailug had 10 sons and six daughters, three of whom are based on Saipan.

Yarofalpiy said his father was buried the day after he died, which is customary in Yap since they do not have a morgue.

To observe the death of a navigator like his father, Yarofalpiy said sailing between islands is banned until the family of the deceased opens up the seas by initiating sea voyaging once again.

“We won't hold it for long. We understand that people need to travel to other islands for food. We plan to open sail nine days after his death,” said Yarofalpiy.

Piailug, who last saw his father when he sailed to Satawal last year, said he followed his father in most of his trips from Satawal to Saipan on a conventional canoe.

“He had diabetes but he was in good condition [then],” said Piailug.

Legend continues

Being one of the last traditional navigators, Mau Piailug trained younger navigators, including Charles Nainoa Thompson, executive director of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, which invited Mau Piailug to support them in their quest to revive the ancient art of Hawaiian wayfaring.

“There are young people that have the knowledge but not like what he did. He's into traditional [method],” said Yarofalpiy.

In an e-mail to Saipan Tribune, Commonwealth Council for Arts executive director Angel S. Hocog offered his condolences to the family of the late Mau Piailug.

Hocog said the death of Mau Piailug is “a great loss” for the Micronesian culture because “there is so much to learn” from the late master navigator.

He added that CCAC is planning to organize an exhibit that will coincide with the Cultural Heritage Month in September to pay tribute to Mau Piailug.

Piailug noted that the continued existence of the art of traditional navigation lies to a great extent on those who have learned from the late master navigator.

“Whoever learned from him should step up and do what they learned. We have to step up and try navigating around and pass the knowledge,” he said.

To continue his father's legacy, Yarofalpiy said he plans to work closely with the Canoe Federation on Saipan and the CCAC and do educational outreach to students.

Yarofalpiy, who has done presentations at Marianas High School and other schools in the past, said he is willing to teach children so they can learn about traditional art and culture.

“It will be up to the young generation to continue this art. That's what we want, to preserve our culture,” he said.

The family of the late Mau Piailug started the nightly rosary last Tuesday, July 13, at 7:30pm and will continue until the memorial service 6pm on July 21 to be held at Santa Soledad Church.

Washington Post, Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Mau Piailug, Micronesian who sailed by navigating sun and stars, dies at 78

By Emma Brown, Washington Post Staff Writer. Photo: Steve Thomas.

Mau Piailug, who died July 12 at 78 on the western Pacific island of Satawal, was one of the last masters of the nearly lost traditional art of using stars, sun and wind to find safe passage across the ocean.

Mau Piailug, who died July 12 at 78 on the western Pacific island of Satawal, was one of the last masters of the nearly lost traditional art of using stars, sun and wind to find safe passage across the ocean.

In 1976, Mr. Piailug made international headlines when -- using nothing but nature's clues and the lessons he'd learned from his grandfather, a master navigator schooled in traditional Micronesian wayfaring -- he steered a traditional sailing canoe more than 3,000 miles from Hawaii to Tahiti.

The journey was a project of the Honolulu-based Polynesian Voyaging Society, co-founded by anthropologists interested in the enduring mystery of how the Pacific's scattered islands, often separated by hundreds of miles of water, had become populated by peoples who lacked nautical technologies such as the compass and sextant.

Many scientists had believed that Polynesians, unable to navigate across vast seas, had arrived on various islands by accident when their boats had floated off course. Mr. Piailug's feat showed instead that indigenous peoples could indeed have deliberately explored and colonized Pacific islands.

Featured in a National Geographic special, the journey also showed the world that traditional navigation was rooted in profound skill. Among Pacific peoples, who were fast becoming westernized, it led to a resurgence of cultural pride and a renewed interest in ancient wayfaring skills.

"The rebirth of non-instrument navigation came about largely due to this man, Mau Piailug," said former Smithsonian secretary Lawrence Small at a 2000 ceremony in Washington honoring Mr. Piailug (pronounced Pee-EYE-lug).

He became an eager teacher, breaking with tradition to share among cultures his closely guarded navigation secrets that had traditionally been passed down only within families.

Among his students were Nainoa Thompson, a Hawaiian who became a master navigator, has many students and has completed long ocean-crossings; and Steve Thomas, a California native who made a documentary and wrote a 1987 book ("The Last Navigator") about the months he spent learning from Mr. Piailug in Micronesia.

Mr. Piailug feared that the powerful pull of Western culture on young Pacific Islanders would eventually lead to the extinction of traditional wayfaring, Thomas said Monday.

"He understood that he had to teach without restriction and without hesitation and spread as many seeds of interest as possible," Thomas said. "He taught me without holding back."

Mau Piailug was born in 1932 on Satawal, a low-lying island that stretched a mile from end to end and is now part of the Federated States of Micronesia in the western Pacific. His grandfather was a palu, a master navigator, and he chose Mau to follow in his footsteps.

Mr. Piailug's lessons began when he was a child. His grandfather had him sit in tide pools to learn the ocean's tug. Later, when Mr. Piailug begin traveling on the Pacific's wide swells and became seasick, his grandfather tied him to the stern of a canoe and dragged him through the water to cure him.

Mr. Piailug memorized the night sky's star map and learned how to read moving clouds and the ocean's swells and reefs. At 18, he was ceremonially initiated as a palu.

He used his skills largely to catch fish and turtles for his family until 1973, when he visited Hawaii at the invitation of his niece and her husband, a former Peace Corps volunteer named Mike McCoy. McCoy took Mr. Piailug to an early meeting of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, where plans were being made for the groundbreaking journey to Tahiti.

McCoy volunteered Mr. Piailug as a navigator, according to a story in the Honolulu Advertiser, and Mr. Piailug didn't protest.

A double-hulled canoe called Hokule'a, manned by 15 Hawaiians, departed on May 1, 1976. It arrived in Tahiti just over a month later despite a period of becalmed seas and mutinous behavior by some crew members, who were unhappy with the journey's white organizers.

According to news reports, Mr. Piailug had more than a dozen children. A complete list of survivors could not be confirmed.

In 2003, Mr. Piailug was the object of a Coast Guard search when he was two weeks overdue on a short 250-mile jaunt between the islands of Palau and Yap.

He and his crew were located by an Air Force C-130 from an Air Force base in Guam; after enduring strong headwinds from a typhoon, they were tired and thirsty -- but they were right on course and just 30 miles from their destination. They finished the voyage under their own power.

"I wasn't worried. I knew right away that it was the weather," said Junior Coleman, a Hawaiian who had previously sailed with Mr. Piailug, in an interview with the Honolulu Advertiser. "I told people to remember who is involved here. He's the Yoda of the Pacific."

The Economist. July 22nd, 2010

Photo by Steve Thomas

Pius Mau Piailug, master navigator, died on July 12th, aged 78

IN THE spring of 1976 Mau Piailug offered to sail a boat from Hawaii to Tahiti. The expedition, covering 2,500 miles, was organised by the Polynesian Voyaging Society to see if ancient seafarers could have gone that way, through open ocean. The boat was beautiful, a double-hulled canoe named Hokule’a, or “Star of Gladness” (Arcturus to Western science). But there was no one to captain her. At that time, Mau was the only man who knew the ancient Polynesian art of sailing by the stars, the feel of the wind and the look of the sea. So he stepped forward.

IN THE spring of 1976 Mau Piailug offered to sail a boat from Hawaii to Tahiti. The expedition, covering 2,500 miles, was organised by the Polynesian Voyaging Society to see if ancient seafarers could have gone that way, through open ocean. The boat was beautiful, a double-hulled canoe named Hokule’a, or “Star of Gladness” (Arcturus to Western science). But there was no one to captain her. At that time, Mau was the only man who knew the ancient Polynesian art of sailing by the stars, the feel of the wind and the look of the sea. So he stepped forward.

As a Micronesian he did not know the waters or the winds round Tahiti, far south-east. But he had an image of Tahiti in his head. He knew that if he aimed for that image, he would not get lost. And he never did. More than 2,000 miles out, a flock of small white terns skimmed past the Hokule’a heading for the still invisible Mataiva Atoll, next to Tahiti. Mau knew then that the voyage was almost over.

On that month-long trip he carried no compass, sextant or charts. He was not against modern instruments on principle. A compass could occasionally be useful in daylight; and, at least in old age, he wore a chunky watch. But Mau did not operate on latitude, longitude, angles, or mathematical calculations of any kind. He walked, and sailed, under an arching web of stars moving slowly east to west from their rising to their setting points, and knew them so well—more than 100 of them by name, and their associated stars by colour, light and habit—that he seemed to hold a whole cosmos in his head, with himself, determined, stocky and unassuming, at the nub of the celestial action.

Sharing breadfruit

Setting out on an ocean voyage, with water in gourds and pounded tubers tied up in leaves, he would point his canoe into the right slant of wind, and then along a path between a rising star and an opposite, setting one. With his departure star astern and his destination star ahead, he could keep to his course. By day he was guided by the rising and setting sun but also by the ocean herself, the mother of life. He could read how far he was from shore, and its direction, by the feel of the swell against the hull. He could detect shallower water by colour, and see the light of invisible lagoons reflected in the undersides of clouds. Sweeter-tasting fish meant rivers in the offing; groups of birds, homing in the evening, showed him where land lay.

He began to learn all this as a baby, when his grandfather, himself a master navigator, held his tiny body in tidal pools to teach him how waves and wind blew differently from place to place. Later came intensive memorising of the star-compass, a circle of coral pebbles, each pebble a star, laid out in the sand round a palm-frond boat. This was not dilettantism, but essential study; on tiny Satawal Atoll, where he spent his life, deep-sea fishing out in the Pacific was necessary to survive.

Nonetheless, the old ways were changing fast. After Mau, at 18, was made a palu or initiated navigator, hung with garlands and showered with yellow turmeric to show the knowledge he had gained, no other Pacific islander was initiated for 39 years. Alone, he went out in his boat with the proper incantations to the spirits of the ocean, with proper “magical protection” against the evil octopus that lurked in the waters between Pafang and Chuuk, and with the wisdom never to get lost—or only once, when he was wrecked by a typhoon and spent seven months, with his crew, waiting to be rescued from an uninhabited island.

As a palu, however, he could not allow his skills to die with him. He was duty-bound to pass them on. Hence his agreement to captain the Hokule’a. That voyage, which proved that the migration of peoples from the south and west to Hawaii was not accident, but probably a deliberate act of superlative sea- and starcraft, transformed the self-image of Hawaiians; and it changed Mau’s life. Suddenly, he was in demand as a teacher. Patiently, pointer in hand, one leg tucked under him, he would explain the star compass to new would-be navigators; but he allowed them to write it down. He knew they could never keep it all in their heads, as he had.

Much of what he knew, of course, was secret. The secrecy was serious: when he spoke of spirits, his smiling face became deadly sober and even scared. To a very few students, he passed on “The Talk of the Sea” and “The Talk of the Light”. By doing so, he broke a rule that Micronesian knowledge should remain in those islands only. It seemed to him, though, that Polynesians and Micronesians were one people, united by the vast ocean which he, and they, had crisscrossed for millennia in their tiny boats.

In 2007 the people of Hawaii gave him a present of a double-hulled canoe, the Alingano Maisu. Maisu means “ripe breadfruit blown from a tree in a storm”, which anyone may eat. The breadfruit was Mau’s favourite tree anyway: tall and light, with a twisty grain excellent for boat-building, sticky latex for caulking, and big starchy fruit which, fermented, made the ideal food for an ocean voyage. But maisu also referred to easy, communal sharing of something good: like the knowledge of how to sail for weeks out on the Pacific, without maps, going by the stars.

Government of the Federated States of Micronesia Information Services. Palikir, Pohnpei, July 23, 2010.

Master Navigator "Mau" Piailug Dies on July 12, 2010

Master Navigator Piailug died on July 12, 2010, at 6:30 pm on his home island of Satawal, Yap State; he was 78 years old. Mau Piailug's passion was ocean seafaring and way-finding; he inspired and taught his own people and many other Pacific Islanders his talents, skills and knowledge in the art of ocean voyaging.

Master Navigator Piailug rose to become a prominent figure in Micronesia and the Pacific region in the mid 1970's to the time of his passing, as he undertook his nearly thirty-four year mission of sharing and teaching his knowledge and skills with the Polynesian Voyaging Society of Hawaii. The Hawaiians had lost their connection to the techniques of traditional ocean navigation despite the fact that the Hawaiian Islands were settled much later than the Micronesian Islands. Piailug was responsible for the revival of interest in ocean voyaging and navigation in Hawaii. He inspired the renaissance in the art now thriving once again in Hawaii and many Polynesian Islands.

Master Navigator Piailug also contributed to the work of the Joint Committee on Compact Negotiation (JCN). When the Compact Agreement was being renegotiated between the FSM and the U.S. Governments, Piailug appeared in Washington, D.C., with the JCN team to tell of FSM's success stories, among them his own in reaching out to help the Hawaiian people.

For his outstanding achievements and contributions, Master Navigator Piailug was recognized by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., as a seasoned seafarer and one of the last surviving master navigators. The University of Hawaii also recognized him for his achievements and contributions to the Hawaiians, by bestowing upon him an honorary doctorate degree.

"Master Navigator Piailug will be missed by all of us in the FSM and the Pacific region," said President Mori, "but his legacy will live on and continue to inspire."

The Kaselehie Press, Kolonia, Pohnpei, Monday, 26 July 2010

Legendary Master Navigator Pius “Mau” Piailug sails on

Written by Bill Jaynes and Tom Raffipiy

Mau, master navigator and progenitor of a new breed of Pacific navigators has died. Pius “Mau” Piailug was 78 years old when he died on July 13, 2010. He had suffered from diabetes for many years≥

Mau, master navigator and progenitor of a new breed of Pacific navigators has died. Pius “Mau” Piailug was 78 years old when he died on July 13, 2010. He had suffered from diabetes for many years≥

He was not the first of the traditional navigators in the Pacific and because of his life and what he chose to do with it he won’t be the last.

Mau’s accomplishments as a traditional navigator who used only the stars, the sun, the ocean currents, birds and keen observation of what was going around him is the stuff of legends. He was the navigator on the 1976 round trip journey from Hawai’i to Tahiti. He violated his own traditions to teach his skills to potential mariners not from his own family or heritage who had demonstrated to him that they were ready to accept the knowledge.

Mau was chosen by his grandfather to be a navigator for his island of Satawal, a tiny island in Yap one mile wide and a mile and half long. It is said that when Mau was young his grandfather took the young child to several tidal pools on the island and laid him there so that he could begin to experience the movement of the water, to look up at the sky and to observe and to learn by simply being.

When he was six years old Mau’s official training began in earnest and he learned from his grandfather the ways of the ancient mariners and navigators.

Nainoa Thompson who studied under Mau wrote an article about the experience and the man fourteen years ago.

Thompson said of Mau in that article, “His grandfather took him out to sail with him at age four. Mau told me that he would get seasick and when he was seven years old, his grandfather would tie his hands and drag him behind the canoe to get rid of that. This was not abuse. This was to get him ready for the task of serving his community as a navigator...

“Mau can unlock the signs of the ocean world and can feel his way through the ocean. Mau is so powerful. The first time Mau was in Hawai’i, I was in awe of him-I would just watch him and didn’t dare to ask him questions. One night, when we were in Snug Harbor, someone asked him where the Southern Cross was. Mau, without turning around or moving his head, pointed in the direction of a brightly lit street lamp. I was curious and checked it. I ran around the street light and there, just where Mau had pointed, was the Southern Cross. It’s like magic; Mau knows where something is without seeing it…

“‘It’s too late,’ Mau said, ‘I am too old, our children have too much to learn, and it’s too late.’ That’s something I never wanted to hear. But he said, ‘It’s okay. All navigators find a way out. When they put me in the ground, it’s all right because I already planted a seed in Hawai’i. When my people want to learn, they can come to Hawai’i and learn about me.’ Mau does not see navigation as cultural revival; it’s his way of life. His people will never come to learn from him until they want to live that way again,” Thompson concluded.

When President Mori’s Chief of Staff received the phone call telling him

that Mau had sailed on to other waters I happened to be close by and I

thought of the many great men of Micronesia I wish I’d had the

opportunity to meet before they passed on; historic and stalwart men

who accomplished so much in their lives. How to write a fitting tribute

to a man like Mau has completely eluded me, though my thoughts have had

an opportunity to incubate within me for nearly two weeks. Ultimately I

found myself unequal to the task, daunted by the vast differences

between his world and mine, and completely overwhelmed by his monumental

accomplishments and the mark he made in this world before he sailed on.

When President Mori’s Chief of Staff received the phone call telling him

that Mau had sailed on to other waters I happened to be close by and I

thought of the many great men of Micronesia I wish I’d had the

opportunity to meet before they passed on; historic and stalwart men

who accomplished so much in their lives. How to write a fitting tribute

to a man like Mau has completely eluded me, though my thoughts have had

an opportunity to incubate within me for nearly two weeks. Ultimately I

found myself unequal to the task, daunted by the vast differences

between his world and mine, and completely overwhelmed by his monumental

accomplishments and the mark he made in this world before he sailed on.

Mau’s nephew, Tom Raffipiy who knew his uncle extremely well had the following to say:

“In his native Satawalese vernacular “mau” means strong, strength, hard,

hardened, and mature, among other definitions. Truly, Pius “Mau”

Piailug lived up to the nickname given to him in his early adulthood.

The name was supposedly given to him to describe his uncanny physique

which was then thought of as a physical defect. The ripples of muscles

on his back were likened to the rough shells of hawksbill turtles.

However he got the nickname “Mau” one can be certain that it was given

out of love and affection as was the normal practice. Probably no one

realized how the name would shape the character of the man who defied

cultural belief to safeguard a dying art of Oceania – non-instrumental

navigation.

“Mau was naturally strong and courageous. Mau would have beem the first

to admit that he might have not known as much “talk of the sea” as most

navigators of his time did, but I knew him to have more courage and to

be more fearless than any of them. Mau would never allow himself to

doubt his decisions and navigational tactics and that served him well

throughout his life. He thrived on challenges and rarely stayed on the

land. He dedicated his whole life to voyaging and to teaching. That was

his passion.

“Mau’s points of view frequently sparked controversies as he would

always speak his mind and often challenged other people’s points of

views that he believed were not in line with cultural practices and

beliefs. He was a man of few words but if presented with the

opportunity, he would speak in burst of words in rapid fire fashion that

could be intimidating to those who didn’t know him.

“Among his major pet peeves was the introduction of Christianity and

western education in the islands. Like many island elders, he believed

western religious practices and schools contributed to the rapid erosion

of cultural arts and sciences that have kept the Pacific Island

cultures alive for generations.

“Like men of his age and those before him, Mau believed that real men

drink alcoholic beverages. Mau drank most of his life and that probably

contributed to the downward spiral failure of his health.

“Mau fulfilled the callings of the traditional navigators and much

more. He did his part in feeding the islands and upholding the

honorable legacy of “pwo navigators.” Unlike many navigators, Mau was

so giving of his knowledge and willing to teach whoever was willing to

learn. Every moment was a teaching moment to Mau. He loved the

dedication of the Polynesian people to learning traditional navigation,

and it’s for that reason that he dedicated half of his life to teaching

traditional navigation to the Polynesian people especially the

Hawaiians. The Hawaiian people were very special to Mau.

“Mau left behind a legacy that is unparalleled and unmatched. Mau will

be remembered by his generous gift of pride and self-identity to the

people of the Pacific. His will be a legacy of teaching islands rather

than individuals. Mau was a visionary man with great conviction in his

knowledge, tremendous physical and mental strength, and unwavering

courage to break the taboos of the teaching of navigation in order to

preserve the precious “talk of the sea.”