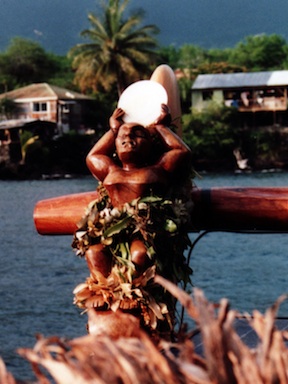

Hōkūle‘a's Ki'i

The ki'i wahine, or female image, lashed to the manu or back-piece of the port hull on Hōkūle‘a, is named "Kiha Wahine o Ka Mao o Malu Ulu o Lele." The ki'i kāne, or male image, lashed to the back manu of the starboard hull is named "Kane o Hōkūle‘a o Kalani." (Traditionally, the port, or left, hull of a double-hulled canoe is female; the starboard, or right, hull is male.)

The ki'i were fashioned by master carver Sam Ka'ai of Maui. Ka'ai keeps the original ki'i under his protection; the duplicates on the canoe are called the traveling ki'i; they are in the keeping of Wally Froiseth. These ki'i embody the spirit of Hawai'i and watch over the canoe while it voyages.

The female image has eyes that represents seeing and foresight; the male image represents knowledge; they work together to guide the canoe. Before the start of a voyage, the feet and legs of the ki'i are wrapped with maile lei.

Taking Hold of the Old Story: Sam Ka'ai, by Sam Low

Sam Ka’ai was brought up in Kaupō, an old district of Hawaiian homesteads in rural East Maui.

Until 1938, there was no road to Kaupō. When they finally put one in, Sam’s father and stepfather worked on it. His family raised pigs and cattle. They fished. They grew papaya, avocado and peanuts. They made okolehao, liquor distilled from ti root. “We grew our own food,” Sam remembers, “so we didn’t know there was a depression going on. We had little need for money. We made our own pipes for smoking. A pipe bought in a store was called ‘a lazy man’s pipe.’” Sam’s father and grandfather made canoes. Sam continued in this tradition, although as a carver of fine sculpture. He used adzes that came down to him from his ancestors. They were fashioned a century or so ago.

Herb Kane traveled to each island to introduce the concept of the voyage, taking the Hawaiian pulse at each encounter. In 1973, Sam Ka’ai went to Maui Community College to listen to Herb talk about Hōkūle‘a. When the talk was over, Sam stood up holding a copy of Honolulu Magazine and pointed to a picture of the canoe. He spoke to Herb in Hawaiian. Herb said “speak English please.”

“We cannot participate in the making of your canoe because it’s going to be in Oahu, so maybe we can make some small part,” Sam said. “In the picture, there are two ki’is (sculpted figures) on the two manus – the two stern pieces of your canoe. Have they been made yet? If not, I will do it.”

It was a busy meeting so Sam gave Herb his address and left. A few days later, a letter arrived from Herb: “if you come from a canoe family, please dream and make your own design for the ki’is.”

Sam carved two ki’is – a man and a woman. The female figure would be lashed to the port manu, the male ki’i to the starboard. When Sam carved the male figure he fashioned his hands reaching up to the heavens in supplication.

Honaunau, 1992 Voyage to Tahiti

“This is an effigy of how we are after so many years of oppression,” Sam explains. “Blind to our past, we reach up to grasp heaven one more time. The same stars are rising at the same time as they did for our fathers for many, many generations. So if you lose your way - if you cannot find your way – remember that you once sailed on your mother’s lap and you were never lost. The stars turned minute by minute, hour by hour, dawn and dusk and you always came home or your kind wouldn't be here. So you were never lost. This is an effigy of the Hokule’a experience – the ohana wa’a, the family of the canoe. He is reaching above himself, beyond himself, to the story that has not changed, the forever and ever story, the olelo, olelo, olelo - down the corridor of time – the lei of bones. He is showing that we are taking hold of the old story once again.”

Canoe ‘Aumākua, by Herb Kawanui Kāne

Throughout Polynesia, the spirits of illustrious ancestors (‘aumākua) are remembered and venerated for their extraordinary talents, abilities, and other manifestations of mana. The living, by emulating such qualities, show their respect for their ancestors, and by such respect they hope to encourage their aumakua to take a beneficial and protective interest in them and bestow mana upon them. Well into the 20th century, Hawaiians learned many of their ‘aumākua by name, and the chants for invoking their help. The scholar Mary Kawena Pukui learned the names of 50 ‘aumākua as a child.

A protective interest on the part of ancestral spirits was especially needed when confronting the dangers of the sea. Much of the elaborate surface carving, ornamentation and carved images typical of some South Pacific canoes may be interpreted as symbolic of protective ‘aumākua. South Pacific carved human images on canoes (tiki, Hawaiian ki'i) are not "gods," but visible objects wherein invisible ‘aumākua may repose when they are present.

Unlike many South Pacific canoes which featured much symbolic surface carving and other ornamentation, Hawaiian canoes were distinguished by their clean lines and the absence of carvings that might weaken their structure or add weight. It's likely that this was a design evolution from an earlier canoe form more similar to South Pacific canoes. The rough interisland waters of the Hawaiian Islands demanded every design component to be rugged and functional, and the sleek form of the the Hawaiian canoe followed its function.

Yet there had to be a place in the canoe for the ‘aumākua as spiritual passengers. Sometimes images were carried aboard. Samwell, with the Cook Expedition in 1778-79, saw small wooden images carried within the stern of some canoes*. However, we have no drawings of them, and this is the only reference. With this precedent in mind, artist Sam Ka'ai carved the ki'i that is carried on the sternpiece (manu hope) of the starboard hull (akea) of the voyaging canoe Hokule'a. An ‘aumakua figure in traditional Hawaiian carving style representing a navigator spirit, it holds aloft a shining pearl shell symbolic of the navigation star, Hōkūle‘a (Arcturus).

There is, however, a small feature of the design of traditonal Hawaiian canoes which provides a place for the benevolent ‘aumākua to ride along with his descendants. This is the momoa, the small tip of the hull projecting at the stern behind the manu hope.

The distinctive momoa is omitted by some modern canoemakers who are unaware of its significance. According to one story, the tradition originated when a chief was leaving "Kahiki" (Hawaiian for Tahiti – probably the Tahitian island of Ra'iatea, anciently named Havai'i) on his return voyage to Hawai'i, and a spirit (‘aumākua) asked to accompany him.

"Where will you ride?" the chief asked. "The canoe was fully loaded with the crew and provisions for the voyage." The spirit said " I will ride upon a small projection I see at the stern end of the hull." The spirit leaped from shore, and rode to Hawai'i on that small projection. Since then, Hawaiian canoemakers have traditionally kept that projection, the momoa, as the place where the ‘aumākua may ride.

*Edge-Partington, James 1899. Extracts from the diary of Dr. Samwell: Polynesian Society Journal, vol. 8. p 262.