Navigating Change:

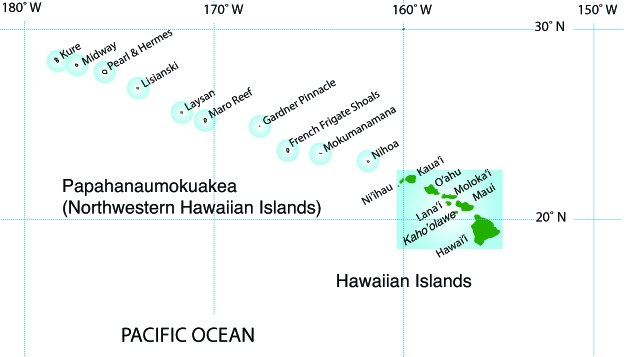

2003-2004 Voyage to Papahanaumokuakea

"Navigating Change" is a project focused on raising awareness and motivating people to change their attitudes and behaviors to better care for our islands and our ocean resources. The project is an educational partnership that includes private non-government organizations, state agencies and federal agencies that share a collective vision for creating a healthier future for Hawai`i and for our planet. This collaborative multi-agency effort aims to change behaviors by creating an awareness of the ecological problems we face and by making it relevant to the decisions that confront us in our daily lives.

In September 2003, PVS sailed Hokule`a along an ancient route to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to examine the cultural and biological wonders of this unique and rarely seen ecosystem. The "ancestral" leg of our journey took us to the islands of Nihoa, where cultural protocols were performed to set the stage for the rest of the voyage.

In 2004, Hokule'a then sailed to Kure, at the western end of the NWHI. (Google Map of the track of the 2004 Voyage from Kaua'i to Kure, courtesy of Michael Shintani.)

Below is the series of articles published in the Honolulu Advertiser on voyage, by writer/crew member Jan Tenbruggencate. Use the menu on the right to access individual articles.

Jan inside his sleeping compartment. Photo by Na‘alehu Anthony

Monday, May 3: Recovering the seafaring tradition of Hawai'i

The voyaging canoe Hokule'a sailed into the darkness last night to begin a historic voyage up and down the Hawaiian archipelago, on a new environmental and cultural mission called "Navigating Change.

"It's 4,000 miles, four months, five legs and 160 crew members," said Nainoa Thompson, master navigator and president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Crews of the various legs participated in a traditional 'awa ceremony yesterday afternoon at Honolulu Community College's Marine Education and Training Center, followed by a fund-raising event for the Polynesian Voyaging Society, which operates the Hokule'a.

Crew members of the Hokule'a and its escort boat took part in an 'awa ceremony at Sand Island yesterday afternoon. The canoe left Sand Island last night, bound for Kaua'i. Rebecca Breyer, The Honolulu Advertiser

The canoe was navigating by the stars across the Ka'ie'iewaho Channel to Hanalei Bay on Kaua'i. They are expected to arrive in Hanalei about midday today under the command of captain and navigator Bruce Blankenfeld. Most of the O'ahu-to-Kaua'i crew will get off, to be replaced by a second crew for the sail to the leeward islands.

Thompson will serve as captain and Blankenfeld as sailing master for the leg from Kaua'i to the leeward, or Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, to Kure Atoll — the most distant point in the chain — which lies more than 1,200 miles west-northwest of Hanalei Bay and almost 1,600 miles from Hilo, Hawai'i.

The Hokule'a will leave Hanalei on Saturday and head for its first stop, Nihoa Island. Navigation to the first two islands will be by noninstrument techniques employed by navigator Ka'iulani Murphy, 25. Beyond that, Thompson said, the canoe's crew will use noninstrument techniques on the open ocean, but will use satellite navigation as they approach the hazardous reefs of coral islands that are difficult to see from a distance.

It is important to reinvolve the people of Hawai'i in knowing and understanding the leeward islands, said semiretired University of Hawai'i anthropologist Ben Finney, who helped launch the Polynesian Voyaging Society and Hokule'a.

"This is really part of Hawai'i's history that has been lost," Finney said.

As of Friday, 60 classrooms throughout the state had signed up to participate in satellite phone discussions with the canoe while it is on its voyage.

Beyond Nihoa is the rocky island Mokumanamana, and beyond that, nearly 1,000 miles of rocks, reefs, atolls and low coral islands. Scientists describe the region as containing some of the most pristine reef ecosystems in the world, full of unique communities of marine life, millions of nesting seabirds and broad expanses of sand, coral and coralline algae reef and pale blue waters.

The Hokule'a, which was launched in 1975, has for most of its existence had a mission of rediscovering ancient Polynesian sailing routes and developing noninstrument navigational techniques like those used by prehistoric Hawaiian and other Polynesian sailors. With this voyage, the canoe adds "Navigating Change" — the mission of protecting the islands and reefs it visits.

"Our focus has always been about raising islands out of the sea, but then, what about the issue of taking care of them?" Thompson said.

The Polynesian Voyaging Society has worked with a long list of government, educational, scientific and cultural partners in developing its new educational mission, which includes a detailed teachers' curriculum.

"It's about the protection of our island home," Thompson said. "Navigating Change is premised on the idea that the main Hawaiian Islands are changing, but the change hasn't been good.

"We're compromising our coral reefs, and to some degree, the ocean is a mirror that reflects the well-being of the islands ... but there are solutions. I don't want to project just doom, but hope. There are agencies doing good work and there are communities doing good work.

"The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands give us an ecological benchmark we can work for. I don't think it's reasonable to expect the main Hawaiian reefs to become like the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. But the baseline should at least express this: Stop the decline."

The canoe will stop at each of the islands and atolls, and the crew has been granted U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permission to go ashore on four of them: Tern Island at French Frigate Shoals, Laysan Island, Kure Atoll and Midway Atoll.

At Midway, most of the crew will be replaced by a crew that will take the canoe back to Kaua'i without stopping along the way. Another crew change there will put a youthful crew aboard for a long voyage to Hilo, which will involve sailing to just north of the Equator and tacking back north to find the Big Island.

This leg is a kind of passing of the navigational baton. None of the most veteran Hokule'a crew members will be aboard. Russell Amimoto will serve as captain and Ka'iulani Murphy as the lone navigator, sailing for the first time without one of the older generation of sailors for backup. Most or all of the crew members will be younger than the canoe they're sailing.

"The old goats are getting off. Us guys are not going to live forever, so it's important that none of us are aboard," Thompson said.

"Bruce and myself and (Big Island traditional navigator) Shorty (Bertelmann) and the others are becoming what our elders were to us.

"They were the mentors, and now we need to be. If you don't accomplish that, then all the work we've done will die with us," he said.

After arriving in Hilo, the Hokule'a will begin a series of sails, with up to 10 visits to locations in each county where important environmental projects are taking place, Thompson said.

May 8, 2004 Hokule'a awaits favorable winds for voyage north

HANALEI BAY, Kaua'i — Hokule'a crew members preparing for a voyage to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were to go aboard today, but the double-hulled canoe is expected to remain at anchor awaiting favorable winds.

Hokule‘a with Rainbow. Photo by Ka‘iulani Murphy

A low-pressure system has blocked the trade winds, leaving light winds of inconsistent direction — a problem for a sailing vessel.

National Weather Service forecaster Bob Farrell said the Hokule'a might see north winds of about 10 mph by midafternoon tomorrow, strengthening to northeast winds of about 15 mph Monday.

"It might be a little higher than that in the channels," Farrell said.

Hokule'a captain Nainoa Thompson said he hopes to be able to leave Hanalei tomorrow.

The crew will use this afternoon to stow gear for the voyage and scrub the bottom of the Hokule'a's twin hulls so that any alien marine growth picked up in the main Hawaiian Islands isn't carried into the fragile marine ecosystems off the leeward islands and atolls.

The canoe's mission combines voyaging and navigation with environmental protection and education. As part of that mission, the Hokule'a took water samples during its sail from O'ahu to Hanalei Bay on Kaua'i this week, and test results confirm what one might expect: Bacterial pollution increases closer to land.

Crew members on the canoe took the samples at the request of the Hanalei Watershed Hui, a citizens group that works to improve the aquatic environment of Hanalei River and Hanalei Bay. The canoe's samples, taken Monday, were compared with samples taken from land around Hanalei Bay the same day.

Watershed Hui chief scientist Carl Berg Jr., an ecologist, said the samples were tested for enterococcus bacteria, which are associated with fecal matter from warm-blooded animals such as humans, dogs and pigs, but "not turtles, not sharks, not other fish." Seals and whales could create such bacteria, but neither species has been seen much in the area.

The samples also were tested for salinity, so that researchers could distinguish samples where fresh water was affecting ocean water.

The tests showed that water collected offshore, with ocean salinity of 35 parts of salt per thousand, consistently had bacteria levels at or below the lowest amount the equipment could measure.

"We got 10 or fewer organisms or colonies per 100 milliliters. That's at the limits of detection of our machine," Berg said.

Once the canoe pulled into the middle of Hanalei Bay, the salinity dropped to 34 parts per thousand and the bacteria count rose to 31 per 100 milliliters.

"Once inside the bay we could detect the nonpoint source pollution," Berg said. The 31 count approaches the Environmental Protection Agency guideline of 35 per 100 milliliters for marine waters.

The Hanalei Watershed Hui's own measurements confirmed the origin of the pollution. Samplings from the various rivers that flow into the bay found 84 per 100 milliliters at Hanalei, 185 at Waioli, 323 at Waipa and 359 at Waikoko. A test of the bay water fronting the Hanalei Pavilion found a 63 count.

"So the bacterial pollution was coming from land sources," Berg said.

The hui's previous studies of water samples upstream from residential uses show there is a background level of enterococcus, probably associated with animals such as feral pigs and rats, but the numbers rise dramatically near homes.

The implication is that the higher counts are the result of human activities, most likely leaking from cesspools and septic systems, Berg said.

"That's why the Hanalei Watershed Hui has received an EPA grant to replace septic systems and cesspools in riparian (river and streamside) areas, and to plan for the creation of a central wastewater treatment plant for the Hanalei town area," he said.

Thursday, May 13, 2004 Hokule'a to remain docked until Sunday

HANALEI BAY, Kaua'i — Hokule'a's departure to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, already delayed for five days while awaiting good sailing weather, has been put off until Sunday.

The National Weather Service is predicting variable winds to 15 mph throughout the state through Saturday, with the trade winds returning Sunday.

Some crewmembers yesterday returned to their home islands to jobs and family for a couple of days. Others opted to stay with the canoe. The entire crew is to regroup Saturday — or tomorrow if the weather clears up more quickly than anticipated — to prepare to sail.

Despite the delay, the 14 men and women who will sail aboard the Hokule'a remained committed to the voyage. The trip's completion is now scheduled for about June 6 at Midway Atoll.

"This crew is awesome," skipper Nainoa Thompson said.

Longtime Hanalei resident Donn Carswell, who downloaded a satellite weather image and brought it down to the canoe, said May weather on Kaua'i's north shore is normally summer-like, with clear skies and northeast trade winds.

"I don't remember when I've seen it like this. This is February weather," he said.

Thompson said National Weather Service forecasters also reported to him that the weather is following a pattern normally seen in winter.

"Generally, low-pressure systems like this dominate in winter. High-pressure systems dominate in summer," he said. The canoe's voyage was planned for May in part because the month characteristically has summery weather, but falls before the June start of Hawai'i's hurricane season.

Thompson said Polynesian navigators would have waited for proper weather to sail, and the Hokule'a will, too. It has to do with giving new navigator Ka'iulani Murphy good conditions for her first navigational command, and with sailing as much as possible in the way Hawaiian ancestors did, he said.

"If we're going to maintain the integrity of the voyage, this is what we have to do," Thompson said.

Saturday, May 22, 2004 Departure unleashes crew's enthusiasm

HANALEI BAY, Kaua'i — Crew members of the voyaging canoe Hokule'a allowed themselves to feel excited yesterday as they prepared for a morning departure for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands after two weeks of delays.

Hokule'a crew members Na'alehu Anthony, left, and Keoni Kuoha lash a guardian figure to the rear left manu of the canoe in preparation for a morning departure. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

"I've got butterflies," said navigator Ka'iulani Murphy.

Others were more effusive.

"This is the epitome of all my dreams come true," said Leimomi Dierks. "I expect to come back with more questions than answers, which is kind of intimidating, but it will fill a big puka (void) in myself."

The double-hulled canoe was to leave at dawn for its first leg, a 150-mile passage to the island of Nihoa, the easternmost of what some call the leeward islands, others the Kupuna Islands — formations older than the main Hawaiian Islands that hold the archaeological remains of Polynesians from before European contact with the main islands.

The crew checked and stowed gear yesterday, inspected the canoe's rigging, and in a moment that quieted everyone on board, lashed two carved figures to the stern: a female figure on the left, or port, manu and a male figure on the right.

The figures represent 'aumakua — family or personal gods — and are seen as guardians or protectors of the canoe. Some consider them the vessel's eyes.

"The canoe suddenly felt different once they were there," said one visitor.

The crew of 15 included trained veterans and newcomers to the canoe.

"This is totally new for me. I have never sailed on the Hokule'a, but it's my fourth trip up the (island) chain," said Randy Kosaki, a biologist with the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve who is a resource specialist for the canoe's educational mission.

"I'll be looking through a cultural lens, not just a biological lens on this trip," he said.

The canoe is under the command of Capt. Nainoa Thompson, sailing master and crew chief Bruce Blankenfeld and navigator Murphy.

They will navigate without instruments to the first two rocky, high islands. But as the canoe approaches the hazardous reefs and atolls from French Frigate Shoals, Murphy will navigate in open water, and the crew will switch to satellite-based measures for safety.

The voyage represents the first trip through the islands by a Polynesian voyaging canoe in the modern age. The re-establishment of a cultural connection to those islands is an important feature of the voyage; education is another.

The crew already has held daily teleconferences with classrooms throughout the state and on the Mainland and American Samoa, and will continue them from the canoe. Educator and crew member Ann Bell of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is leading the teleconferencing program, and said the canoe represents a powerful tool to interest children in learning.

"The kids already have an emotional attachment to the canoe. ... They know it is special to Hawai'i," Bell said. "We have a responsibility to bring (the leeward islands) back to the kids of Hawai'i, because it's their archipelago, their back yard."

Monday, May 24, 2004 After delays, Hokule'a voyage finally begins

AT SEA, WEST OF KAUA'I — The voyaging canoe Hokule'a sailed westward out of Hanalei Bay yesterday morning on a brisk southeast wind, finally.

Bruce Blankenfeld, right, and Russell Amimoto were among the Hokule'a crew members who acknowledged boatloads of well-wishers yesterday as they left Hanalei Bay. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

The night sky early yesterday was full of stars; the morning greeted a rising breeze with clear skies and puffs of white clouds overhead.

After 15 days of weather and other delays, the crew slipped the mooring lines about 9 a.m. with canoe loads of well-wishers cheering alongside. Motorized, sail-powered and paddled outrigger canoes cruised along as the twin-hulled Hokule'a picked up speed.

The 29-year-old canoe and its crew of 13 are on a voyage through the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, following a route organizers believe is similar to one used by Polynesian voyagers hundreds of years ago.

It is also an educational mission, bringing the science, the culture and the excitement to students across the state of the experience of taking an ancient form of transportation through islands that have been dubbed the Kupuna Islands — the elders.

People on shore and on the boats following the canoe for the first mile blew traditional Hawaiian greetings on shell and bamboo pu. The canoe responded with the wavering harmonics of two different-sized pu blown in unison.

Before yesterday's departure, half the crew slept aboard the canoe, and the others took advantage of a donated condominium, where they could wash clothes, shower and sleep in beds for the last time in weeks. Most have been waiting by the canoe since its original departure date of May 8, supported on shore by a Kaua'i community that pitched a large tent and provided meals and cars for the duration of the wait.

The canoe crew, the escort boat crew and members of that community stood in a wide circle on shore before yesterday's departure as voyagers thanked the people of the island, and the island folk thanked the canoe crew for voyaging.

"We thank you for doing this for us, for our children," said Cathy Ham Young, who oversaw the on-land support of the crew.

Hokule'a eased down the north coast of Kaua'i past Ha'ena, and then fell into the wind shadow of the island. The crew raised bigger sails and tacked out to sea until they picked up a steady 20 mph wind and a following sea.

The course kept Kaua'i on the port side of the canoe, and Ni'ihau misty in the distance to the right of Kaua'i.

The canoe was to sail to an imaginary line between Ni'ihau and Nihoa, a small rocky island Hokule'a first visited in September 2003, and then down that line to the island. Navigator Ka'iulani Murphy, 25, on her first long-distance solo navigation trip, has captain Nainoa Thompson and sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld to turn to if she needs help. Both are accomplished non-instrument navigators. But they were committed to remain silent except in two instances — if Murphy asks for help, or if they believe she is severely off course.

On the way to Mokumanamana, Hokule‘a sailed past Nihoa. Photo by Na‘alehu Anthony

Thursday, May 27, 2004 'Tiny little island' greets Hokule'a

OFF MOKUMANAMANA — An exhausted crew led by sleepless, red-eyed navigators surfed a following sea through the day and night to make a picture-perfect landfall yesterday morning at Mokumanamana.

Hokule'a's crew spotted Mokumanamana about 10 a.m. yesterday, 28 hours after leaving Nihoa. Crew member Ka'iulani Murphy was the lead navigator but drew on the experience of captain Nainoa Thompson and sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld to make a pinpoint landfall. Murphy called it a team effort.

Navigator Ka'iulani Murphy, exhausted after having stayed awake for more than 30 hours during Hokule'a's voyage from Nihoa island, took the opportunity to catch a nap after crew member Russell Amimoto spotted the island of Mokumanamana. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

"It was amazing. This tiny little island in the middle of the ocean," said navigator Ka'iulani Murphy.

The same swell that had challenged the sailors through the 28-hour passage made it impossible to anchor at the island, where whitewater climbed the rocky island's sides.

The canoe made a pass along the southern side, stopped for chants and the ceremonial blowing of a pair of pu, Hawaiian shell trumpets.

Hokule'a then proceeded under reduced sail for French Frigate Shoals. The speed was reduced to allow for a morning departure at the island. Captain Nainoa Thompson said the canoe's navigators will point the course without instruments as they have thus far, but from this point on will keep track of their exact location with satellite-based global positioning system receivers. The reefs of the atolls northwest of Mokumanamana and Nihoa are too low to see from far away, and it would be too dangerous to sail the canoe through them without the help, he said.

"Our first rule is safety," he said.

Murphy, who had made her first solo non-instrument navigation from Kaua'i to Nihoa Sunday and Monday, called the Nihoa-to-Mokumanamana voyage a team effort, in which she consulted with Thompson and sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld.

Thompson credited the entire crew of 13, saying it took good steering and seamanship as well as navigation to get Hokule'a to its destination.

The sail is one of the most challenging passages in the 1,500-mile Hawaiian archipelago for traditional navigation, both because its 155 miles make it the longest inter-island channel in all Hawai'i, and because Mokumanamana is so small a target.

While Nihoa is 900 feet high and covers 150 acres, Mokumanamana has just 45 acres and is about one-third as high.

Thus, while Thompson spotted Nihoa from nearly 30 miles out, watch captain Russell Amimoto spotted Mokumanamana just a dozen miles out. A lower, smaller island is even harder to see.

And while the canoe came up on Nihoa several miles north of the island, Mokumanamana appeared right on course, visible between the canoe's twin front manu.

Murphy said Thompson had recommended a course change at 8:30 or 9 a.m. yesterday to account for waves having pushed the canoe off course to the north more often than to the south during the night's steering. Without the course change, Hokule'a would have sailed a course a mile or two north of the island — still well within the range of visibility.

Once the island was sighted, student Murphy and mentor Thompson, who had both been awake the entire voyage so far, took naps—Thompson under cover in one of the canoe's bunks, and Murphy on deck with a jacket over her head.

Mokumanamana is an enigmatic island. Also known as Necker Island, it has very little soil, but is spotted with 33 Polynesian-design stone shrines whose origin is clouded. Some believe they may have marked repeated ceremonial visits to the island hundreds of years ago.

In addition to the shrines, archaeologists have found stone tools and other artifacts that appear very much like those found in the main Hawaiian Islands. Radiocarbon dating suggests the island was first inhabited several hundred years after the main Hawaiian Islands were populated, and that visits to the island stopped some time before European contact.

The island is narrow and rocky, with a few species of native plants growing in the small amount of soil. It is shaped something like a fish hook with its shaft lying east-west and its hook pointing north from the west side.

Hokule'a crewman Tava Taupu said it was easy to find rock formations that looked like faces — something he has seen frequently in his nearly 30 years of sailing on Hokule'a.

"I find all the islands have something like that," he said.

As the canoe moves from the two volcanic islands to the reefs and atoll islands, the voyage's mission changes somewhat from one featuring navigation as its hallmark to a greater emphasis on natural science and education.

The canoe continues to be in daily contact with school groups, who can ask questions about sailing aboard the voyaging canoe. Crew members will be doing volunteer conservation work at French Frigate Shoals, Laysan Island and Kure Atoll. The voyage is entitled Navigating Change, and one goal is to use the wildlife-rich Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to encourage people in the main islands to take better care of their home islands.

May 30, 2004 Crew sets sail for Laysan

TERN ISLAND, French Frigate Shoals — It starts with the green clouds, and as you get closer to this 22-mile-long reef complex, the amazements just keep coming.

Overhead are hundreds of thousands of wheeling birds; on the beaches, green sea turtles not much smaller than a Volkswagen and Hawaiian monk seals bigger than NFL linemen.

In the water, the wildlife all seems oversized by main Hawaiian Islands standards. Big scarred ulua, huge nenue, whitetip sharks, tiger sharks, Galapagos sharks.

The waterline on La Perouse Pinnacle could have been painted by Van Gogh, with vibrant blasts of colors — yellows, lavenders, greens, reds and more. The algae are so rich because they are fertilized by the guano that whitens the top of the pinnacle and seeps down the sides when it rains, said Hokule'a crewman Randy Kosaki, a marine biologist with the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.

La Perouse Pinnacle. Photo by Na‘alehu Anthony

The crew of the voyaging canoe Hokule'a sailed up to French Frigate Shoals Thursday and stayed two nights before leaving yesterday morning for a 2 1/2-day sail to Laysan Island. Continuing east winds and swells prompted Captain Nainoa Thompson to bypass Gardner Pinnacles. He said the downswell sail from Gardner to Laysan would be too hard on the canoe and crew.

The crew spotted the green clouds over the reef immediately. They are known in the South Pacific as a tool for native navigators. Long before you spot an atoll, you can often pick up the green of the atoll's waters reflected against the clouds.

And it's a surreal thing at French Frigate Shoals. In the distance are your standard gray and white clouds, and nearby, the clouds are distinctly, unmistakably green to the naked eye. Seen through Polaroid sunglasses, they positively glow.

The white undersides of birds flying over the lagoon also turn green.

On Friday, the crews of Hokule'a and the escort motorsailer Kama Hele helped with a sea bird protection project on Tern, hauling sheets of steel plate to cap a 60-year-old rusting seawall that was trapping young sea birds. The still-flightless chicks would waddle to the edge and fall between sheets of flaking steel — often injuring themselves.

The canoe and escort crews were amazed at the wildlife. Crew members dove at La Perouse Pinnacle, where they swam with 6-foot white-tip sharks, a passing seal, a turtle nearly a yard across and a large very black white ulua.

"They turn black when they're angry or aggressive," Kosaki said.

Coral reef researcher and crew member Kanako Uchino, from Japan, said the ulua surprised her.

"It doesn't look like he's scared. He just come close to me, and swing around me and constantly coming back to me — like he was checking us out instead of us checking him out," Uchino said.

Sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld said that's what was special about the French Frigate Shoals wildlife. "The wildlife, they're at home there. They're comfortable. They're unthreatened.

"I was impressed by the sheer numbers of birds. They are an integral part of this planet, this ocean planet, and the health of the planet depends on the ocean. I've never seen that kind of numbers. It gives you a good feeling to see that kind of abundance," Blankenfeld said.

Marine researchers from a variety of agencies participate in research at French Frigate Shoals, working out of an old Coast Guard facility on Tern, the largest of the reef's islands.

Researchers collect all kinds of data, from shark-attack scars on seals to assessments of their scat and spew, said Suzanne Canja, a Maui resident who is the field camp leader for the monk seal team of NOAA Fisheries, an agency of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

"Almost every adult seal has shark scars," said Dan Luers, a marine biologist from Ohio in his third season at Tern.

In 1997, there was a persistent problem of male seals "mobbing" or attacking females and pups. Many pups died, and Galapagos sharks started feeding on them around Trig Island. Since then, Galapagos sharks have been returning annually to eat seals during the pupping season.

That's just one of the problems seals face. Some estimates are that there were as many as 2,500 Hawaiian monk seals in the 1950s, but the population declined to about 1,300, despite massive research for more than a decade.

Some researchers believe that the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are a source of other marine life in the main islands as well, that larvae from the abundant marine life here help resupply Hawai'i's depleted reefs.

"There is a very nice hopeful spirit, to be next to the extraordinarily diverse abundance of life," Thompson said.

The double-hulled canoe's mission, in part, is to bring home to the people of Hawai'i the possibilities of a healthy environment, the kind found in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

"That sense of wildness makes me feel better, makes me feel hopeful," Thompson said.

Canoe turns back

Hokule'a turned back toward Tern Island last night because of an injured crewmember. The voyaging canoe was being towed back to French Frigate Shoals because the wind was against it.

The crewmember fell against a wooden railing and suffered a back injury.

Dr. Cherie Shehata said that it was not an emergency situation, but that the crewmember — who asked not to be identified — needed medical attention that was available on Tern Island.

Hokule'a was about 60 miles out when it turned back. It was not known what effect the situation would have on the remainder of the voyage.

Monday, May 31, 2004 Hokule'a captain will sail on despite injury

TERN ISLAND, French Frigate Shoals — Captain Nainoa Thompson has been injured aboard the Hokule'a but will continue on to Midway — a 10-day voyage — because doctors fear it is too risky to fly him home. The voyaging canoe was to sail from Tern Island before dawn today, after an emergency return to the island on Saturday. The canoe will continue its mission of sailing through the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Thompson will remain aboard because a team of Honolulu physicians agreed by telephone with the canoe crew's doctor, Cherie Shehata, that he would be safer on his beloved twin-hulled vessel than aboard a small unpressurized aircraft — the only kind that can fly into the 3,000-foot coral strip at Tern.

The veteran sailor, non-instrument navigator and chairman of the Kamehameha Schools board of trustees suffered a back injury Saturday afternoon when he was thrown against the end of a thick wooden railing as he worked at the front of the port hull.

He said it was the first injury he has ever suffered aboard the canoe.

Shehata, speaking about Thompson's condition with his approval, said the injury initially appeared to be a severe bruise with a possible fractured rib or ribs. That is a special concern because a broken rib could puncture a lung, and Thompson only has one. The other lung was removed years ago because of injury.

"If it's fractured and it gets hit again, it could puncture the lung, and I don't have another one. I'm a liability on board," he said yesterday morning.

After Thompson was brought to Tern Island by a Fish and Wildlife Service boat yesterday, Shehata said four Honolulu physicians who reviewed the navigator's condition agreed that a significant lung puncture would have presented specific symptoms by that time, and such symptoms were not present.

But there was risk. Doctors said there might be a minor lung injury, and an unpressurized flight could cause more problems. The doctors said Thompson was better off on the canoe, as long as he was protected from possible further injury by resting and not being allowed to do physical work.

He can still navigate.

And by the time the canoe reaches Midway on June 9, he should be well enough to fly.

After Thompson was injured, Shehata ordered the canoe to return to Tern, where evacuation and other options would be available sooner than if the canoe proceeded the several hundred miles to the next island with an airfield, Midway.

Hokule'a was 60 miles northwest of French Frigate Shoals, which it had left Saturday morning. Canoe sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld, Thompson's brother-in-law, held a crew meeting at about sunset and reviewed what was known about Thompson's condition. He said the canoe would be towed by escort vessel Kama Hele, because it would take too long to sail into the wind to reach Tern.

"This is something that we're prepared for, something we plan for," he said.

It was already dark. The crew quickly prepared a tow line. Two large orange buoys were attached to the end of the tow line, and glow sticks were tied to the line every 12 feet, so that the escort boat could see the lay of the line.

Then the tow line was fed overboard and allowed to drift away from the canoe. The Kama Hele approached the lighted line and hauled it aboard with a boat hook. Shortly, Hokule'a was being pulled toward French Frigate Shoals at about 5 miles an hour.

Thompson was walking around the canoe, although gingerly and clearly in some pain.

Shehata immediately began contacting other doctors by satellite phone. She also called the crew's insurance carrier, Divers Alert Network; the Fish and Wildlife Service, which operates a wildlife station at French Frigate Shoals; the Coast Guard; and Thompson's family. Hokule'a was towed through the night, arriving at the French Frigate Shoals mooring at 11 a.m. yesterday.

After the decision was made for him to stay aboard, Thompson met with escort boat captain Tim Gilliom, Blankenfeld, Shehata and other crew members on Tern, and outlined a revised trip up the chain. They were expecting to arrive at Laysan Island Wednesday morning and end up at Midway by June 9.

Thompson said he regretted having to turn the canoe around, but felt he had to concur with the physician's decision.

"We as an organization by principle say safety is first. We bring a doctor on board as a resource, a specialist necessary to keep the voyage as safe as possible. To compromise that level of safety is simply not acceptable," he said.

Shehata said a well-developed emergency plan helped the process.

"It went smoother than I thought it would. Everyone organized themselves. Those who knew about the radio box gathered around it. ... People set about steering the canoe," she said.

The canoe carries extensive medical supplies in two large coolers and a large dry bag.

"It's like an outpatient clinic. I have antibiotics, pain medication, sutures, seasickness medicines, things to deal with colds, infections, sprains, casting material for bone breaks," she said.

Blankenfeld said the canoe has dealt with all kinds of medical conditions, including broken bones, cuts needing stitches, severe infection, people knocked unconscious. For medical problems and every other issue that might occur, the Polynesian Voyaging Society has tried to develop procedures, he said.

"There are procedures for every emergency down the line," Blankenfeld said. "Here we are, implementing the procedures."

Thursday, June 3, 2004 Canoe crew ashore on Laysan's sands

LAYSAN ISLAND, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — Hokule'a pounded around the northern end of Laysan at sunset, its twin bows plunging into the seas, water sluicing across the deck and the crew huddled in foul-weather gear.

The canoe slipped into an anchorage Tuesday in quieter waters on the lee side for the night. Crew members went ashore yesterday morning, after moving the canoe to a spot near shore, protected by reefs.

Voyaging canoe Hokule'a anchored at dawn off Laysan Island during its voyage through the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Escort vessel Kama Hele is at right, with a dinghy between them. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

Before they disembarked, though, the bow of the canoe was converted into a surgery suite, to stitch up a gash on biologist Randy Kosaki's index finger, received while opening a contact lens container with a pocketknife on a rolling ship, in alternating shade and full sunlight, with wind blowing briskly.

Dr. Cherie Shehata gave him four stitches.

"My wife's going to be rolling her eyes when she hears about this," he said.

Kosaki slipped a plastic glove over his bandaged hand and prepared to join the crew ashore. He was snorkeling by afternoon.

Laysan is a beautiful sand-dune island, with white shores, a cluster of coconut palms and an interior lake that's highly salty.

Eragrostis grass provides habitat for several species of wildlife on Laysan Island. The salty central lake is visible in the background. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

It is also a story of environmental degradation and rejuvenation. Guano miners, feather poachers and an ill-fated rabbit-canning business around the turn of the century converted Laysan from a coastal forest wonderland of flowering plants and sandalwood trees into a sand-blown desert.

The rabbits were perhaps the worst. After the canning business failed, they were left to proliferate and they ate off nearly all the vegetation. Native land birds became extinct, including an orange honeycreeper closely related to the 'apapane of the main Hawaiian island forests.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is overseeing the restoration of the island—stabilizing, replanting, removing weeds and conducting the research needed to bring it back to some semblance of former glory.

"This is an example of what we need to do in the main Hawaiian islands," said captain Nainoa Thompson. "This little island is a microcosm of where we have been going. Also, it talks about where we need to go. We need to look for ways to renew, heal and give hope," Thompson said.

Hokule'a crew members carried a special set of clothes when they went ashore, and they changed into them at the waterline. Each piece of clothing had been bagged, brand new, and frozen for at least 48 hours, all to ensure that no live weeds or insects came to the island.

After their arrival on Laysan, Hokule'a crew members meet for a briefing on the ecosystem of the island, which is recovering from the ravages of guano mining, feather poaching and feral rabbits. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

"One of the gravest threats to the unique Northwestern Hawaiian Islands ecosystems is the introduction of alien species," said Fish and Wildlife Service biological technician Stefan Kropidlowski.

Each camera, each watch or pair of sunglasses was inspected and wiped down.

Is it overkill?

The service has spent more than a decade eradicating one weed, which presumably arrived as one seed stuck to someone's pant leg. This common sandbur — the same one that sticks to your foot or your trousers when you walk near the shore in many parts of the main islands —began taking over habitat once held by tall clump grasses that birds use for nesting and food.

"The introduction of a grass called the common sandbur altered the natural composition of vegetation and eliminated nesting habitat for the Laysan finch, the Laysan duck and several other species of birds and insects. The Fish and Wildlife Service has spent the last 12 years combating this plant and it appears we are finally winning the battle," Kropidlowski said.

The rule for these islands, which are all wildlife refuges, is that the needs of humans are secondary.

"Wildlife comes first," said Beth Flint, wildlife biologist for the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex.

Monday, June 7, 2004 Northwest islands dotted with wrecks of old vessels

LAYSAN ISLAND, French Frigate Shoals — Hokole'a's crew, hauling hundreds of pounds of marine debris from Laysan's beaches, repeatedly trudged through soft sand by the rusted bow and flaking machinery of a wrecked steel fishing boat.

The rusting hulk of a wrecked fishing boat pierces the sandy beach at Laysan Island. It is one of dozens of ships wrecked in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands during the past two or three centuries. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

It is just one of the dozens of craft that have come to their ends on Hawai'i's leeward islands, which stretch like a vast rock and coral trap 1,200 miles from Kaua'i to Kure Atoll.

The wrecks still happen every few years. In recent decades, the victims have mainly been fishing boats, but decades and centuries past, they have been coal carriers, sail-powered whalers, military ships, tankers, pleasure craft and many more.

Many had survivors, who reported the wrecks. Many more, it is assumed, did not. There is still a lot of surveying to do, but even among those areas that have been swept for lost ships, there are mystery wrecks, said marine archaeologist Hans Van Tilburg, maritime heritage coordinator for the Pacific Islands Regional Office of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Sanctuary Program.

It's even possible that Spanish treasure galleons filled with Mexican silver wrecked here. Spanish ships crossed from Acapulco to Manila once or twice a year from about 1565 to 1810, he said.

Van Tilburg was interviewed before Hokole'a started its voyage through the islands.

One problem in identifying old wrecks is that islands are subject to huge storms, powerful seas and occasional tsunami, and old wooden ships would have left little evidence behind.

"That's a high-energy environment," Van Tilburg said.

The rough seas, tricky currents, difficult-to-spot shoals and reefs and narrow passages are among the reasons why Hokole'a's captain, Nainoa Thompson, abandoned non-instrument navigation once passing the volcanic islands of Nihoa and Mokumanamana and entering a region with an 800-mile stretch of reefs, shoals and banks.

Before approaching any low island he pores over maritime charts and often keeps two global positioning system satellite navigation units running at once — each as a check for the other.

"It's too risky, too dangerous" to take lightly, he said.

The canoe sailed up to Lisianski Island yesterday morning, but anchored three miles from shore. Coral heads and reefs, many of which are poorly charted, surround the island. The crew dived on the reef for half an hour, then raised anchor and sailed for Pearl and Hermes Atoll, which it expected to reach this morning.

Although he said the coral and marine life are remarkable there, he opted to sail by Maro Reef entirely.

The many wrecks would appear to justify his caution.

There are wrecks that could be serious threats to the environment, like the 1957 loss on Maro Reef of the Navy oil tanker Mission San Miguel. It was not carrying a cargo of oil when it went down, but would still have had a lot of residual oil in its tanks, plus its own fuel oil and other fluids.

When the Navy tried to salvage it, there was too much oil in the water for divers to work and the salvage was abandoned. And when folks returned to the site later, the ship was gone.

"It had been high on the reef, hard aground, and then there was no trace of it any more. We assume it launched itself into the deep," Van Tilburg said. One fear is that some of its tanks are still whole, but deteriorating, and that they will ultimately fail and cause a major oil spill.

"The topic worldwide is an important one. The Navy could pump it out if it is shallow enough. It would be nice to confirm its location in case it starts leaking," he said.

The captain of the three-masted copra schooner O.M. Kellogg, which wrecked on Maro in 1915 while bound from Samoa to San Francisco, complained a month later in The Honolulu Advertiser that "I think it is always bad weather at Maro Reef."

And as Hokole'a sailed by south of the reef last week, there were dark rain squalls on Maro.

The most important known marine archaeological find in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is probably the 1870 wreck of the USS Saginaw at Kure Atoll, Van Tilburg said.

He and a crew of divers in August 2003 found remains from the Navy ship, including two small iron cannons, iron anchors, metal rudder fittings and copper pins that once held the major timbers together.

The Saginaw had been sent to nearby Midway to blast a channel, so a coal fueling station could be established there. The ship had been built during a period when sail power was giving way to steam. It was a hybrid: a coal-fired, steam-powered side-wheeler that carried masts and sails.

All 93 men aboard survived the wreck, and lived on Green Island, a flat sand and coral islet just inside the reef.

Five of the crew sailed a small boat for help. They made it 1,200 miles to Kaua'i, but they were extremely weak by then. Four died while landing in the rough surf. The crewmembers who remained on Kure, eating seal and albatross meat and drinking rainwater, all survived.

Van Tilburg said he would love to do more work on the wreck, including trying to find the remains of the survivors' camp to see what can be learned about how they lived.

Shipwreck survivors need to be innovative, because they often have few resources.

Survivors of the 1842 wreck of the whale ship Parker at Kure used pieces of copper from their own wreck or the previous wreck of the ship Gledstanes to make cooking utensils.

Wrecks were such a common occurrence that the crew of one rescue ship in 1886 planted trees and built two 500-gallon water tanks with a rain gutter system to aid future victims on Kure. But vandals from other ships had destroyed the improvements within a year.

Tuesday, June 8, 2004 Marine debris proves to be real threat to voyage

PEARL AND HERMES ATOLL, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — The voyaging canoe Hokule'a sailed to an anchorage for a brief stop here yesterday morning, but during the middle of the previous night it had not been clear the canoe would make it.

A little after 11 p.m., the crew of the escort boat Kama Hele reported "a problem with the engine." The problem: It had stopped abruptly.

Engineer Steve Garrett at first suspected a transmission problem. Someone finally jumped into the water and diagnosed the problem: a twisted mess of drifting ropes had wrapped around the single propeller — another threat of marine debris.

Escort boat crewman Palani Wright calls attention to a pile of washed-up ropes and nets on Laysan that Hokule'a's crew helped cut up and haul from a beach. Bins in the background contain more marine debris. Such debris can entangle seals, turtles and sea birds. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

Near midnight, with no moon and with the dark, deep ocean below, crewmen Kiyoshi Amimoto and Tim Gilliom went over the side with lights and knives. Hokule'a took down its sails and drifted in wait two miles ahead.

The two cut through rope after rope, stopping occasionally to scan the waters around them with lights for predators. They got it free, and by midnight, both Kama Hele and Hokule'a were again under way.

Hokule'a's crew applauded Amimoto and Gilliom when the two boats anchored at Pearl and Hermes.

Shortly after dawn, the canoe had its biggest day of fishing to date. Four handlines were trolling behind the vessel. Suddenly one hit, then another, and as they were being hauled in, a third, and then the fourth. The crew hauled in two kawakawa and two small 'ahi.

One of the lines was fed back out to aid in untangling it, and another fish hit, got loose, hit again, got loose again and then hit hard a third time. It was another small 'ahi.

The crew had a fish chowder and teriyaki fried fish on Sunday night with that day's catch, made by sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld. Yesterday, Russell Amimoto and Tava Taupu made a heaping platter of sashimi and fried fish at lunch, and the crew was arguing over whether to have 'ahi spaghetti or more sashimi for dinner.

The sashimi was served on cabbage. The canoe's cabbages were still usable, but only after several layers of blackened and rotted leaves are removed from the outside, and black spots are cut out of the inside.

The only fruits left were shriveled lemons and limes. Onions were OK. Potatoes were soft and turning green. Squashes and sweet potatoes still looked good, but hadn't been tried.

The canoe has done well with eggs. The voyage is into its third week without refrigeration, and each egg is float tested — if it sinks it's deemed OK. If it floats, it's assumed to be bad. As of yesterday, all eggs had been good.

"Last voyage, they lasted 27 days," said watch captain Russell Amimoto, the younger brother of Kiyoshi Amimoto, who helped clear the escort boat's propellor.

The ship's doctor, Cherie Shehata, has been busy with one or more medical issues daily. Captain Nainoa Thompson appears to be doing well after injuring his ribs a week ago off French Frigate Shoals, although he had some soreness after snorkeling yesterday.

Shehata has also stitched a gashed finger, taped a possible broken toe, worked on a jellyfish sting, dealt with seasickness, and responded to leg rashes and abrasions.

She's a triple threat who also works the sails and steers, and in recent mornings has cooked crew breakfasts.

Pearl and Hermes is the second-largest atoll in the Hawaiian archipelago. These low coral islands are difficult to spot, even though we were using satellite navigation techniques and knew where Pearl and Hermes was. Three miles from it we could see no sign of it.

At about two miles, from the deck of Hokule'a, an occasional spot of white on the horizon suggested surf breaking on a reef and at 1.6 miles we could pick out a narrow line of cream-colored sand, distinct from the bright white of the surf. It was Southeast Island, the largest of the sandbars here.

We'd been looking for the green clouds we'd seen at French Frigate Shoals — white clouds that turn chartreuse from the reflection of the shallow lagoon water. We didn't see them on our approach, because there weren't any low clouds at all over the lagoon — although we spotted the green wonders later.

Next we could pick out the hump of swells, rising up before they broke on the fringing reef, and then we could see a line of pale bluish green on top of white breakers. It was the inside of the lagoon. Sooty terns came screeching by, and we spotted a turtle swimming. The water under the boat was getting paler as it shallowed.

About a third of a mile out, we could pick out the steady roar of the breakers. The sand island we were approaching grew thicker with closeness, and what at first looked like greenery on its 10-foot highest point turned out to be a cluster of green tents occupied by a NOAA Fisheries seal monitoring team. There isn't much land vegetation on Pearl and Hermes.

A few hundred yards off the reef, we could pick up detail. We could see the pale blue patches of sandy bottom on the outside of the reef, the pale green shallower sandy patches inside and the darker green areas inside where coral and algae reefs were. Beyond that, there was darker blue water of the deeper areas inside the lagoon.

After our brief diving stop, we sailed on for Kure Atoll, the end of the Hawaiian Archipelago. We hoped to walk on Green Island there and dive its reefs before sailing to Midway, where this crew would leave the canoe and a new crew is waiting to take Hokule'a back home.

Wednesday, June 9, 2004 Hokule'a reaches Kure, end of voyage

KURE ATOLL, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — The voyaging canoe Hokule'a anchored yesterday inside the lagoon at Kure Atoll, the northernmost island of the Hawaiian archipelago.

The event marked the end of a historic 1,200-mile journey from Kaua'i in which the vessel was the first Hawaiian canoe in modern times to follow the rocky islands and atolls up the island chain.

Along the way, crew members employed high-tech methods to keep in touch with schoolchildren in dozens of classrooms and to update Web sites, while using only their hands and the most basic of tools to improve the environments of the islands they visited, hauling marine debris off beaches, planting native species and carrying in the canoe's twin hulls small plants from one island to be established on another.

The canoe was to hoist anchor at sunset yesterday for a sail back toward Midway Atoll, where another crew was waiting to return the Hokule'a to Kaua'i.

Captain Nainoa Thompson said the final day of the voyage north was particularly difficult, but the destination worth the effort.

"The day to get here was rough. ... The winds were shifting and steering was difficult, but we were able to tuck into this little anchorage and were able to anchor on this perfect sandpit," he said.

The crew could look down into crystal-clear waters and see details of the reef 40 to 50 feet below. "This is not just a healthy but a wealthy habitat. This is one special jewel on the planet Earth," Thompson said.

While the rest of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is under federal control, the most remote, Kure, is a state wildlife sanctuary. Hokule'a crew members were able to visit Green Island, the larger of Kure's two sandy islands, where a two-person National Marine Fisheries monk seal team and a three-member state crew are spending the summer.

It is colder here than in the main islands. Not only is Kure more than 1,000 miles west of the main islands, it is nearly 400 miles farther north from the equator.

One effect is that corals don't grow well, said marine biologist Randy Kosaki, and some of the fish species are related to cold-water species from Japan.

Thursday, June 10, 2004 Hokule'a crew brings voyage to close

MIDWAY ATOLL — It felt as if the ocean didn't want to let us go.

Hokule'a arrived at Midway yesterday, completing an 18-day trip that took the voyaging canoe and its crew 1,200 miles from Hanalei Bay, Kaua'i, to Kure at the far end of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Photo by Tim Bodeen, USFWS

The voyaging canoe Hokule'a, after sailing the length of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, ran into a gale returning yesterday from Kure Atoll to Midway Atoll. The canoe arrived unscathed but six hours behind schedule, about 4 p.m. Hawai'i time.

Crew members, with no cover from the piercing rain and whipping wind, huddled wet and miserable in foul-weather gear. Winds exceeding 45 mph and breaking seas swept over the twin bows.

The canoe was being towed into the wind to reach Midway, where a new crew was waiting to take the vessel to Kaua'i. The escort boat Kama Hele, which can normally easily tow Hokule'a at 8 mph, was driven to a near standstill, making just half a mile an hour.

Captain Nainoa Thompson ordered sails opened to ease the tow until the wind was blowing from dead ahead. When it appeared little progress was being made, the two tall spars that lash the main and mizzen sails to the canoe were lowered — a dangerous proposition at sea, and one that required the efforts of the entire 12-person crew. The reduced drag increased towing speed to about 2 mph.

The canoe inched toward the atoll, climbing and plunging down short, 5-foot seas. Raindrops stung on the skin, and felt like gravel bouncing off the eyeballs of those steering. Albatrosses and other seabirds continued to call and swoop and feed as if nothing were amiss.

Sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld prepared four large coils of rope, which would be lowered over the bows to slow the canoe when it ran downwind into Midway's Sand Island harbor. The crew set up anchors on both bows, to be dropped to stop the canoe in case of an emergency.

Thompson ordered inexperienced crew members to don life preservers and sit out of the way of veterans working with lines and buoys.

Squall after squall swept across the canoe, increasing wind speed and adding to the downpour. Midway's Sand Island was tantalizingly visible in the distance, and then gone in a dark gray mist of rain.

As Kama Hele pulled up alongside an old wreck inside the Midway channel, its crew radioed that they were experiencing fuel problems. The engine coughed. Thompson and Blankenfeld huddled by the radio, awaiting word. The problem cleared, and the rocking tow continued.

Members of the crew of the return voyage arrived in a small boat, bringing word of conditions in the harbor. Once inside, the wind continued strong, but the swells were gone. The crew in the small boat took a line to the tugboat pier, and Hokule'a set about tying up.

Half an hour later, the incoming crew had its soggy gear on deck, preparing to remove its presence from the canoe, and the cleaning and reprovisioning was set to begin.

The canoe's crew sailed — and towed on three occasions, one of them a medical emergency — for 18 days from Kaua'i's Hanalei Bay to Kure, 1,200 miles that includes the 10 islands and innumerable reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

The mission of the voyage is Navigating Change, and it's a partnership of numerous agencies, including the Polynesian Voyaging Society, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state Department of Land and Natural Resources, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve, state Department of Education, various University of Hawai'i departments, and others.

Its goal, in part, is to raise awareness about the unique environment of Hawai'i's leeward islands, sometimes called the Kupuna Islands, and to bring home lessons that can be applied in the main Hawaiian Islands.

The canoe spent its longest period at Laysan Island, where the crew participated with Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries field camp scientists in several environmental projects. It sailed by Mokumanamana, Maro Reef and Gardner Pinnacles due to sea conditions and time constraints.

The Kure stop Tuesday was a thrill for several crew members, who had a couple of hours on Green Island, on the same day that scientific camp members arrived. That meant no one had been on the island for months, and that treasured glass fishing floats could be found.

Those who went ashore came back with glass balls ranging from a little bigger than a golf ball to bigger than a basketball. There were enough to go around, and each crew member ended up with a glass ball to help remember the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands trip.

Saturday, June 11, 2005 Mystery disease killing coral

Giant table corals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are suffering from a poorly understood disease that kills off large patches of coral tissue.

White and brown patches on Northwestern Hawaiian Islands corals show signs of the mysterious "white syndrome" first noticed in 2003. Photo by Greta Smith Aeby

Greta Aeby, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands research coordinator for the state Division of Aquatic Resources, said the disease, which she is calling "white syndrome," appears to be similar to a condition afflicting table corals in Samoa, Johnston Atoll and Australia. Its cause is not known in any of those locales.

"If this disease is as damaging as it appears it is, it might be prudent to try to control it," she said. But first, scientists will have to find out what's causing it.

The table coral affected is known to science as Acropora cytherea. It can form broad, oval platforms as much as 6 feet across. The species is not found in the main Hawaiian Islands.

Aeby said she took samples from the corals to be studied in laboratories. It's not known whether "white syndrome" is a bacterial or viral disease, or comes from some other source.

Aeby said she is satisfied that the coral death is not associated with reef animals that feed on corals.

"We have crown-of-thorns (starfish), coral-eating snails and coral-eating fish, but they leave characteristic signs, and it's not them," she said.

Aeby said the disease is spreading fast, particularly at French Frigate Shoals, where the state's largest beds of table coral are found. She saw none of it when she dove there in 2002.

"This is not a subtle disease. I was looking for disease that year and I didn't see it," she said.

She located a single diseased coral in 2003 and three in 2004. She returned this week from a monthlong research trip through the islands with the new NOAA ship Hi'ialakai, and found that five of six sites she checked there had the disease. She established permanent markers at the locations so she can return to the same coral heads in coming years to view their progress.

"We need answers," she said. "Does the disease progress and kill the corals? Does the coral stop it? Is water temperature or some other environmental factor associated with it?"

Aeby also is watching another oddity observed during the research voyage: certain corals were suffering bleaching. Reef corals under stress often eject the internal algae that help feed them and also give them their color. Without the algae, the corals weaken and can die if conditions don't change to allow the algae to repopulate the coral polyps.

There was a severe bleaching event in Northwestern Hawaiian Island corals in 2002, when warm temperatures, sunny days and calm winds heated the atoll waters during the late summer. This year's event is much less severe, but Aeby said it's worrisome that it was occurring in May when waters normally are well within the corals' normal temperature range.

"I didn't anticipate bleaching at all because the water was cold, but we have installed water temperature recorders, so we should be able to track changes in the future," she said.

Randy Kosaki, chief scientist on the Hi'ialakai's recent voyage, said that most previous research trips have been in the early fall, and that one of the reasons for this year's trip was to view the condition of the reefs during a different time of the year.

"It was a very minor bleaching event, but we were surprised to see it at this time of the year. But part of the reason for this cruise was to look at things temporally out of synch with what we normally do," Kosaki said.

Saturday, June 12, 2004 Hokule'a begins trip home

MIDWAY ATOLL, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — The voyaging canoe Hokule'a pulled out of the old Navy harbor at Midway's Sand Island shortly before noon yesterday for its trip back to the main Hawaiian Islands.

As the canoe pulled out of harbor behind its escort boat, blasts from Hawaiian shell trumpets or pu sounded from the crew members remaining on shore, from the canoe and from the escort boat.

The vessel was expected to take about nine days to complete the trip, much of which time it would be heading into the trade winds under tow behind the escort boat Kama Hele.

"We'll sail as much as we can," said Bruce Blankenfeld, who is serving as navigator on the voyage.

Hokule'a on Wednesday completed a historic 18-day voyage through the length of the Northwestern Hawaiian islands, with stops at several. The canoe left Hanalei Bay on May 23.

The northbound crew sailed to Kure Atoll, the most distant island in the archipelago from the main islands, and then backtracked to Midway, where a new crew was waiting. The sailors assisted in debris cleanup and other work that supported conservation on some of the islands where they stopped.

Midway is a former Navy base and now a national wildlife refuge operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It also supports an airfield used as an emergency landing spot for aircraft flying across the Pacific.

While the crews waited for crew member Kealoha Hoe to arrive by air Thursday night, several of them fed fish. Rainy weather had made a load of canoe-dried fish rather soggy, so the crew fed it to a school of massive ulua that was swimming with a giant kahala in the Midway Harbor.

Midway residents threw a party for the Hokule'a crew and departing refuge volunteers Thursday night at the old Navy All Hands Club. A band made up of Thai nationals who work on the island provided entertainment.

Moloka'i resident Mel Paoa is serving as captain on the sailing canoe, which is traveling with a crew of 10 on the southbound sail. They include Paoa, Blankenfeld, Hoe, Terry Hee, Nohea Kaiaokamalie, Gary Yuen, Ka'iulani Murphy, Mike Taylor, Keoni Kuoha and Tava Taupu.

Blankenfeld, Murphy, Kuoha and Taupu also sailed on the northbound voyage.

The escort boat crew is unchanged from the earlier cruise, and includes Tim Gilliom, Kawai Hoe, Palani Wright, Josh Dang, Kiyoshi Amimoto and Steve Garrett.

Sunday, June 13, 2004 Voyage raises challenge

MIDWAY ATOLL, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — Hokule'a is voyaging back to the main Hawaiian Islands now, but the crew members on its historic 1,200-mile island-hop up the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands said the community created by that voyage endures.

What also has endured is a sense that thinking as a community is what can help save a community.

"I have a lot of questions right now. This voyage has changed me," said captain Nainoa Thompson. "It has raised the issue of our values and our vision back home."

The voyaging canoe left Hanalei Bay on Kaua'i May 23, sailing to remote, poorly charted anchorages. The vessel stopped by uninhabited islands and others populated only by maintenance and scientific teams.

Its crew members planted native plants and hauled away marine debris. They sailed by endangered sea turtles and Hawaiian monk seals, dived in waters with sharks and massive ulua, walked beaches occupied by giant nesting albatrosses and tiny fairy terns, whose appearance at sea Thompson said is an indication that land is nearby.

The Hokule'a's 12-member community, half of whom were not veteran sailors, struggled together in good sailing and in bad, and brought themselves and the canoe home safe, officially ending the expedition Wednesday.

Reflecting on the voyage, marine biologist Randy Kosaki of Waimea on the Big Island said he was impressed by the reverence with which the crew approached land, bringing ho'okupu, or gifts, from their own islands. Led by cultural specialist Keoni Kuoha, they also offered chants and prayers to the islands.

"The respect that we give this place, the ho'okupu — the main Hawaiian Islands are no less sacred, yet we rarely give them this respect," Kosaki said.

Veteran Hokule'a sailor Tava Taupu, a native of the Marquesas Islands and now a resident of Kona, said he was struck by the abundance of sea birds that have disappeared on his native islands within his lifetime because of egg collecting and the effects of invasive alien species.

Voyaging on the canoe reminded him that the environment can be protected if people think of it as crew members think of each other and of the canoe.

"Just like on the canoe, we need to check on each other, take care of each other. It's like the canoe is yours, it is home for you. If you take care, it take you 1,000 miles, you go far, far. If not, you break apart," Taupu said.

The spare resources on the individual islands in the northwestern chain that some call the Kupuna Islands, or elder islands, reminded some that in Hawai'i we could be much more conscious of our use of resources, said crew member Leimomi Dierks.

"Living on these islands, living on the canoe, it's a challenge at first, but it's so doable," she said. "The vision is that you malama the land and take care of the wildlife. You learn to not waste resources, learn to conserve."

On Laysan, the killing of sea birds for their feathers, the taking of their eggs, the mining of guano and the introduction of alien species such as rabbits turned a green forested island into a sand desert. Today, wildlife crews are trying to restore it. It's tough work, and it's a lesson for us, said Kanako Uchino, a coral reef researcher from Japan.

Hokule'a crew member Kana Uchino sits on the deck after a dive at Pearl and Hermes Atoll. The tails of five fish caught yesterday morning are visible in the red bucket in background. Photo by Jan TenBruggencate

"We are showing the islands' precious wildlife and how fragile it is. Once you break the balance, it's really hard to bring it back, and it's so easy to break the balance," Uchino said.

Some suggest the Kupuna Islands should be restored and left alone, but that misses the point of one of the lessons of the Hokule'a voyage, according to Kawai Hoe, one of the captains of the escort vessel Kama Hele. The key is to learn how humans can be part of the environment without threatening its survival.

"I dislike the idea that wildlife is separate from humans. We're part of the system. For myself, this is about bringing the families back together. These islands are parts of a family that had been lost to each other. Some people are saying that this voyage is a once-in-a-lifetime thing. Hopefully it's not that. Within the last 200 years, we have screwed things up. Now we have to learn to put them right," Hoe said.

The Polynesian Voyaging Society, working with many partners, dispatched the canoe under the banner "Navigating Change," a concept whose basis is that if the community doesn't plan for the kind of future it wants, it will get the kind of future it doesn't want.

As when an anchor is hauled on the canoe, if only one or two people try, the anchor doesn't come up. But if many people pull, each does less work and the anchor comes aboard.

"What we're doing with 'Navigating Change' is to get people to do a little. If everybody just did a little thing, it would make a big difference. Like using biodegradable soap, because everything ultimately goes to the ocean, and all you have to do is change brands," said sailing master Bruce Blankenfeld.

"The whole spirit of malama is that you always leave a place better than you found it."

Thompson said the success of the voyage will be measured by whether people respond to the message.

"There seems to be a sense that, yes, there are concerns for our future, but there is hope when we come together in community," he said.

Tuesday, June 15, 2004 So far, it's smooth sailing for Hokule'a

The voyaging canoe Hokule'a was sailing along the south side of Maro Reef late yesterday afternoon on its voyage back to the main Hawaiian Islands from Midway Atoll.

The canoe left Midway under tow by the escort boat Kama Hele about noon Friday for what was expected to be an eight- to 10-day passage to Hanalei on Kaua'i.

Hokule'a was heading roughly east-southeast, sailing in northeast tradewinds of 15 to 20 miles an hour. Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld said the canoe dropped the tow line and started sailing Sunday near the eastern edge of Pearl and Hermes Atoll.

"We're doing better than we expected. As long as it stays northeast, we should be able to skirt the southern side of the islands as far as French Frigate Shoals," Blankenfeld said.

The canoe carries a satellite transponder that automatically sends its position periodically to a satellite. The position is regularly updated on the University of Hawai'i Web site, hokulea.soest.hawaii.edu.

Late yesterday, the site showed that the return voyage initially followed a path north of its outbound course, and then crossed and has been sailing south of the course for the past day or two.

The canoe drags fishing lures during the day to supplement canned food on board. Blankenfeld said the crew caught a 15-pound ono Saturday, but had not caught anything since.

The 10-member crew is broken into three three-person watches. Each watch is in charge of the canoe for four hours, and then has eight hours off. Captain Mel Paoa serves as a crewman on one of the watches. He is a mobile intensive care technician and is also serving as the ship's doctor, but Blankenfeld said there had been no call for those services.

Wednesday, June 16, 2004 Big, unique fish thrive in distant waters

Coming home: The voyaging canoe Hokule'a was sailing an east-southeast course yesterday on its way from Midway Atoll to Hanalei Bay on Kaua'i. The vessel was south of Gardner Pinnacles yesterday afternoon, roughly 600 miles from Kaua'i.

When Hokule'a crew members jumped into the water at La Perouse Pinnacle on their recent 1,200-mile voyage, the first things they saw were a huge black ulua and a pair of human-sized reef sharks.

The dramatic population of fish with big mouths and sharp teeth is what immediately strikes anyone who enters the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

When Hokule'a sailed northwest through the archipelago May 23 to June 9, divers among the crew saw very large ulua — 50- to 80-pounders — at every stop, and sharks on several occasions.

There also are lots of smaller, seaweed-eating fish, but in sheer size, the most impressive species are the ones that marine biologists call apex predators, including ulua, sharks, monk seals and groupers or hapu'u.

"Apex predators make up something like 58 percent of the biomass of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, compared to about 3 percent in the main Hawaiian Islands. The fish community looks top-heavy," said Randy Kosaki, research coordinator for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.

"It's an indication of the impact of fishing pressure in our islands," he said.

At first, the balance of the fish seems impossible. How could the percentage of predators outweigh the prey?

Kosaki said studies are planned, but the best guess is that the coral atolls are such a productive ecosystem that prey replace themselves as fast as predators eat them.

And because the reef resources aren't being aggressively fished by humans, more food is available to the big fish.

One of the other interesting features about the atolls is that fish inhabiting deeper waters in the main islands are found in shallow water there.

The grouper is an example, he said. In the main islands, it is seldom seen in water shallower than 300 feet, but in the atolls, they show up at snorkeling depths of 20 to 30 feet.

The masked angelfish, normally found at depths of several hundred feet in the main islands, is another example. At Pearl and Hermes atolls, Kosaki pointed out a pair of masked angelfish in about 25 feet of water.

The atolls also are unique in their percentage of fish found nowhere else in the world. The term for this is endemism, and it refers to species that have evolved into new and unique forms in a particular region.

"As you approach the northern atolls, particularly Kure and Midway, the proportion of endemics increases," Kosaki said. He said about half the total number of fish present is endemic.

Some of the more unusual species are related to fish from southern Japan. Among these are the Japanese angelfish and two species of a reef fish called a knifejaw.

The Japan connection may be associated with the length of the Hawaiian archipelago, close to 1,400 miles from Hilo to Kure's Green Island. Kure and Midway are 1,200 miles closer to Tokyo than they are to Los Angeles.

Kosaki said the central islands, notably French Frigate Shoals, are home to giant table corals called acropora that are virtually never seen in the main islands.

The nearest reefs where these are found are on Johnston Atoll, 700 miles from Honolulu and less than 500 miles from French Frigate Shoals. Kosaki says young corals and other marine species may have drifted north from Johnston.

"Johnston is an intermediate stepping stone between Hawai'i and the South Pacific" for marine life looking for a shallow-water home, he said.

Thursday, June 17, 2004 Wonders blossom under the sea

Coming home The voyaging canoe Hokule'a, returning to Hawai'i from Midway Atoll, was about 500 miles from Kaua'i late yesterday and was expected to pass south of French Frigate Shoals before dawn today. Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld, interviewed via shortwave radio, said the crew expects to arrive at Hanalei Bay on Saturday or Sunday. "We've got clear skies and nice sailing," he said.

When Hokule'a crew members dived on the reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, most of the ocean floor they saw was not coral, as you might expect, but plants — marine algae.

At Lisianski Island and at Pearl and Hermes Atoll, the bottom was covered with a low, leafy turf-like cover that was a mixture of crusty white and green.

University of Hawai'i botany professor Isabella Abbott said it may have been halimeda, which, when it dies and breaks up, is responsible for making much of the sand on the islands' beaches.

At Kure, there was a purple-gray bottom of coralline algae, with only a few coral heads. The reef formed long sand-bottomed channels, caves and arches that provided habitat for hundreds of fish.

The plant life of the northwestern islands also includes what UH-Hilo marine science professor Karla McDermid called "nifty sea grasses." These are grasses and not seaweeds. There are two kinds, Halophila hawaiiana, found only in the Hawaiian archipelago, and Halophila decipiens, found all over the world.

"They are flowering plants. Their flowers look like little crocuses, the size of the fingernail on your little finger," Abbott said.

"To me, they look more like tulips," McDermid said. Coming home The voyaging canoe Hokule'a, returning to Hawai'i from Midway Atoll, was about 500 miles from Kaua'i late yesterday and was expected to pass south of French Frigate Shoals before dawn today. Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld, interviewed via shortwave radio, said the crew expects to arrive at Hanalei Bay on Saturday or Sunday.

"We've got clear skies and nice sailing," he said.

The flowers produce pollen, and the pollen floats in the ocean.

The tiny leaves of these seagrasses are only an inch or so long and are shaped like canoe paddles.

"They are growing in meadows," McDermid said. "The turtles love them."